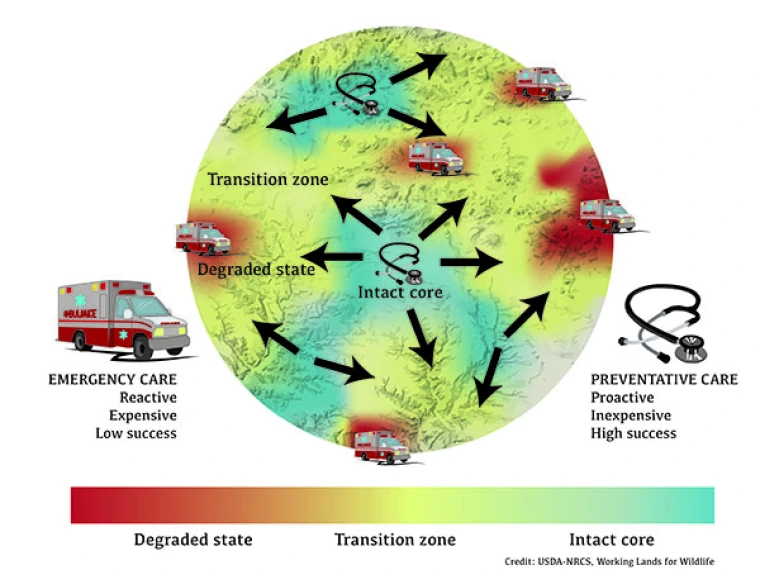

Management recommendations for limiting undesirable ecosystem state shifts driven by cheatgrass in the West and Eastern red cedar on the central US grasslands can now be outlined with greater certainty. Jeremy Maestas, NRCS National Sagebrush Ecosystem Specialist, and Dirac Twidwell, range and fire scientist at University of Nebraska-Lincoln, present the Defend the Core framework for invasive species management, a fresh approach that prioritizes preventing degradation where intact, functional plant communities exist and reducing risk of invasives spreading from areas already compromised. After a hundred years of trying to understand invasive plant dynamics, we now recognize that preservationist passive management will not cause degraded plant communities to return to a reference state.

If you pulled up this episode and haven't listened to part, you might want to listen to episode 99 first.

Transcript

<p>[ Music ]</p>

<p>Welcome to the Art of Range, a podcast focused on range lands and the people who manage them. I'm your host, Tip Hudson, range and livestock specialist with Washington State University Extension. The goal of this podcast is education and conservation through conversation. Find us online at artofrange.com.</p>

<p>[ Music ]</p>

<p>This is the second episode in our two part interview with Jeremy Maetas and Dirac Twidwell on the defend the core framework. If you're just tuning in on this 100th Art of Range release, be sure to go back and listen to the first episode on defend the core, episode 99.</p>

<p>[ Music ]</p>

<p>>> Yeah. I've got a quick question about the intact core that I think will transition us to discussing the transition zone. It would be a good segue. You know, with invasives that are mostly driven by seed, sort of like the body, you're trying to prevent pathogens and reduce exposure to these invasive seed sources. But say a little bit more about how we strengthen or maintain perennial plant vigor. And I guess the 800 pound gorilla here is grazing. I don't know what percent of you know short grass prairie, tall grass prairie, mid grass, mixed grass, and sagebrush, shrub, steppe ecosystems are grazed, but it's a pretty large percentage pretty large percentage of those biomes or ecosystem types. You know, do you think you could say anything about what kind of grazing will strengthen or maintain perennial plant vigor in order to defend the core, you know, which is the - I feel like it's the other side of the same coin. You know, one is to keep the organism healthy. The other is to avoid or prevent pathogens. What can we say about grazing in a way that maintains the ability of these most dominant perennial native grasses to occupy the site and stabilize soil?</p>

<p>>> Yeah, that's a great question. You know, I've learned a lot from Chad Boyd, and Kirk Davies over there at the ARS Burns station as well from on this topic in particular, and they've done, you know, long term research on the effects of grazing on that resilience and health of our perennial bunch grasses, which are really those keystone species in these range land ecosystems. And their work basically shows that, you know, moderate utilization is completely compatible with maintenance and propagation of these perennial bunch grasses that are so key to keeping invasive annuals out. So I think, you know, I won't go into all the different ways you could get there. But if you keep that in mind, I think there's a lot of flexibility in how you get there and achieving that. But it's certainly that that sensitivity side of the equation and you know, constantly have that propagate pressure of seeds coming in. Having a strong robust, native plant community that can one, occupy niche space and two, respond after a fire to keep these invaders out is a really important part of the equation.</p>

<p>>> Yeah, I would agree with that observation. Just in my own thinking and observations I you know, the way I say it is that it's it appears pretty consistent across even different grassland ecosystem types in plant physiology that light to moderate per plant defoliation and, you know, a landscape wide utilization tends to cover over a multitude of sins. And it leaves room for other things to go wrong if the grazing is not excessively heavy.</p>

<p>>> Yeah, Tip, I think that's a great point. And you know, I just love the point in the question. That was one of the first, I guess, really big moments of like internal crisis for ranchers in place where they're like, well I don't have this problem and of course, you know, it's because of how I graze. And yet there's all these long term studies in range lands across the US that show the same thing over and over again. And so we were really clear. We developed this guide for reducing risk and vulnerability to woody encroachment. And really excited about you know where Jeremy kicking that very similar process off for cheatgrass with partners in the Great Basin. But we were really clear on this point just because of, I guess there were two big myths. One was that a single restoration and I'm done, which doesn't work. And number two right, like so I can just keep grazing however I graze and I'll do a single restoration, and cool. I can keep doing the status quo. Number two is well, I don't have this problem and it's because of how I graze. And what we showed in that was that all the long term research, very similar - it can change the rate, but it's not magical. You still there are certain things that grazing and cows by themselves don't deal well with and those are the ones that tend to be really hitting us nowadays. And so as part of that, you know, [inaudible] intact zones, our warning is that it's easier to manipulate and target grazing when you haven't been hit by larger scale issues and you're not surrounded by the threat. So it can give even the appearance that, oh look. My grazing can keep this in check. I can manipulate the movement of my animals, other things, you know, adjust stocking rate. But then if you're an island, as Jeremy said, surrounded by the threat, surrounded by annual invasions, versus if you have some cheatgrass and you're surrounded by high quality, intact rang, it is a different story. The rate at which transitions start to move totally changes. The story is like the Flint Hills, as an example. No matter how much they try and manage [inaudible] encroach and everything else, they're feeling the pressure of now being an island surrounded by a woody dominated biome that's shifted over. So I think that's what hard is we feel like our grazing save us often. And it's like well, yeah. It can change the rate. It can make us less sensitive to these issues. But the more exposure you get, the more that that's where you're going to get tested. So I think that's really important for that transition zone. Right. When we were leading back back into the transition zone, often what I'd like to see is where we shouldn't if people aren't ready to commit in that transition zone especially as you see this expanding and moving, we wouldn't be recommending in the Great Plains for example right now to invest hundreds of thousands of dollars for a localized removal of heavy infestation if they have no plan on how to keep rehabbing back to that healthy rangeland they want. We don't want to set people up to fail and do that horror story of Texas where we sold the ranch three times to pay for brush management. The same is true with annual invasions with cheatgrass. So where their cultural will exists, and there's the desire and intention to rehab to where we want to be and anchor and take the pressure off, that's where we're going to be more successful. Or even if we're in the transition zone and you know what? I know that I'm going to be perpetually managing this. There, at least, we have a plan. We haven't had a plan for the heavy infestation, the transition zone, the intact core, and we haven't created customized solutions that can work for diverse private landowners. So I think we're finally getting there. But I really point to like we have some long term rules of thumb that maybe aren't as applicable anymore. Maybe that's why we have some of these issues, and we just need to question some of those assumptions as we go forward.</p>

<p>>> Yeah. You know, I want to carry through with this grazing discussion because it is so pertinent to the range profession and always it's the most ubiquitous land management tool out there. Right. So we naturally look to it as potentially helping us manage these problems. You know, I think about, again, the context that's provided with these maps when we lay out the landscape context of an invasion problem. Take for example, targeted grazing, and fuel breaks, and those types of practices that are often discussed in conjunction with invasive annual grass management, and fire mitigation in the Great Basin. Those two things, in particular, out of context can be highly controversial. I mean, you want to pick a fight in a community with your environmental groups just start talking about implementing those on public lands in the name of cheatgrass and fire prevention. Right, wrong or indifferent, that's going to be a tough discussion without some context for what's actually going on. So if we're in the Snake River plain, and I can show you that we've already transitioned the annual grasses and we're never going back, what a great place for fuel break networks, targeted grazing. And our goal there is not to eradicate cheatgrass, but to reduce the fine fuels that that carry those annual fires. In our transition zones, we might think about, you know, more explicitly incorporating [inaudible] season grazing which can help reduce the standing biomass to find fuels and the spread. But it's not going to address the seed source, right. It's just going to help us with that additional disturbance that may aggravate the problem. Whereas if you're in an intact core region, and you propose, you know, heavy disturbances, or, you know, fuel breaks in particular, you know, we really have to start to ask ourselves is that what's needed? Or does that introduce new vulnerabilities with that exposure piece? So we're bringing in more potential seed sources that weren't there. So, it really informs, you know, these the intensity of our practices and the types of grazing strategies across that whole spectrum.</p>

<p>>> Yeah. And I think some of that social transition is part of what I was alluding to in the introduction. I think people are beginning to realize that the magnitude of the problem is such that in some places like these, you know, threatened transition areas, it's worth, even if you're anti grazing, it's worth, at least, considering more targeted grazing, you know, to use that term, as a necessary evil, to attempt to reduce the risk of fire because reducing the risk of fire is a pretty big deal. I see some of that. There's more receptivity to that concept now than there has been in the past.</p>

<p>>> Yeah, absolutely. I mean, I think as some interesting examples. You know, as these ecosystems transition to something else, you start to see culture shift in what people expect from the land and so, you know, they've become more comfortable with some of these aggressive management practices. They start to convey things like the importance of cheatgrass for livestock forage. And I laugh because I went out to Nebraska and heard concerns there with the woody encroachment. You know, down in Texas and Oklahoma where it's a much more pervasive problem, you actually have producers who want to keep cedars for deer, you know. And so people just learn to adjust their baseline and their expectations to a degraded state. Not that that's the right thing to do, but that's what happens, and I think we become more accustomed to accepting what it's going to take to live in those novel environments.</p>

<p>>> Well in people that have experienced restoration failures, or at least, you know, a faux pas, even if it wasn't a failure but like in southern Idaho, there's plenty people that have seen places where there was a pretty effective herbicide treatment that maybe got rid of cheatgrass, but you ended up with Medusa head in its place, and that made cheatgrass look like it would have been preferable.</p>

<p>>> Yeah. [Laughs].</p>

<p>>> It's not a one time treatment. You got to do more than one thing.</p>

<p>>> Absolutely. You know, in the 1850s, it didn't matter, right, if you nuked all the vegetation, it was just a matter of time till it came back to some mix of native plants. But now we have this whole suite of invasive species from all around the world just waiting in the wings. So we absolutely have to be cognizant of that native vegetation and how we're managing that.</p>

<p>>> Right. How to direct the successional trajectory when you've got all of those things that are a possibility in the mix. I can't remember I want to say it was in the paper that you mentioned in these threatened ecosystems zones, that one of the grazing strategies that can be effective is not just considering or increasing the amount of dormant season grazing but also specifically to decrease growing season grazing in order to maximize perennial plant vigor and promote seed production. Am I recalling that that was in the paper, or is that my own invention or edition?</p>

<p>>> I'm scratching my head wondering if I said that. But I don't disagree that, you know, our perennial bunch grasses are incredibly important to the resilience of our range lands in the intermountain west. They don't reproduce every year and they're, you know, sitting there waiting for the right conditions. And so we have to be thinking about that ecological cycle of those perennial plants and the replacement of them. You know, kind of, I guess, west of the Continental Divide, especially we've underestimated the importance of bare ground. Bare ground has, I guess, been somewhat demonized, but it's a natural component of these systems. And you know, there's an inverse relationship with the amount of fire you have in bare ground between these perennial bunch grasses. So some interesting science, I guess, to think about. With this invasion problem, you know, it's been often branded or characterized as "the cheatgrass fire cycle", and therefore, we try to rush to treat the fire side of it. And what are some of the new science from Joe Smith, University of Montana, and he was sponsored by ARS on this, but they looked at, you know, like, what's actually causing, you know, cheatgrass transitions across the region. And only a tiny fraction of the lands that have transitioned to annual grasses happened after a fire. Most of the lands that are transitioning have never seen a fire in recent history. So that's telling us that we need to focus more on this invasion ecology side of the equation because these plants are just invading interspaces between some of our bunch grasses. And so we have to kind of tackle it at that reproductive ecology as Dirca was talking about level.</p>

<p>>> It's kind of like Tip early on. I mean, it's so easy for us to just get be looking at one side of the coin and not flip the coin over. So you know, hey. Is this the stressor or a symptom of you know, what's happening in the system? Well, you know, fire's not thinking, right? It's not we kind of view it like it's a living, breathing organism. You know, that's just chemistry and physics playing out. And, you know, depending on where you are, or the context, it's a stressor or not. And depending on where you are, it's and it's for sure, the other side of the coin too, right? It's just changing as the and part of that system. I mean, these are flammable ecosystems as much as a modern society we want to decouple from that, you know, and only have internal combustion, not the old external combustion on lands. But these systems burn and that's been a truism of the Earth system. Like what's happening with rain and drought, right? Like drought has been around forever. Well, it's a stressor and a symptom of what's happening in the system. And so when you flip the coin back and forth, all that you're left with is like, well, what can we do about it? Right? Like, how do we if it's playing both, how can we navigate change given our ingenuity and so forth? I think that's where this field's going.</p>

<p>>> All of the attributes of fire are in effect - they're from, you know, various conditions of the [inaudible] interface. I've had similar, I guess, like a surprise. Having moved to Idaho from Arkansas. I, have been pretty surprised at the fact that every single year we have fire prone conditions. The way much of the West looks like on August 1, you would call a severe drought anywhere else. But if, you know, if drought is being short on rainfall relative to an average, we don't, that often, have that in the West because we have a pretty reliable, at least much of the Northwest in the Great Basin, we have a fairly reliable wintertime precipitation pattern such that there's not as much variation around the mean even though there is a significant amount. But I've seen some resiliency graphs that combined precipitation and temperature, and the variability if you combine the two is significantly greater on the east side of the Rocky Mountains than it is over here. But on this side, we have conditions, you know, say from July 15 to whenever rain comes that are fire prone every single year, and it gets still surprises me that we don't have more acres in the West that burn than we do.</p>

<p>>> Well, you just nailed it. I mean, right like, you know and we're talking about the Art of the Range Podcast here and everything else. I mean, just go back, and it's so easy for us to forget this history. I mean, Jeremy was talking about it with new generations become used to the new normal. And you brought up the example from Arkansas. And when I came over to the Great Plains, working on long term experiment stations like the SoAR Experiment Station, Texas, you know, that was a site where they had pictures from 1916 and so forth. I mean, our profession back then, right? We were you could see rocks, like the, you know the limestone, outcrops, and everything. It just looked like a parking lot and rock. The very few shrubs and trees you had had some browse lines on them. But you're going back, right? And how we managed grazing, given that back then the range professions biggest, you know, value and commodity was the animal, the bees, our profession has now grown and changed. We're now - right, rangelands is about the entire ecosystem. There's things that if it changes on rangelands, it affects cities, and metros, and every citizen in these states, where it's not just about the cows anymore. Well, we got good at managing our cow. There's other special problems now that are emerging at scale, that if we don't get better at managing those as well, you know right like coming out of that century ago, hey. We got to change how we think about grazing. Well we need to take that same mindset mentality and broaden that because we have additional classes of problems, and we have additional needs that we're managing for. It's not just the animal condition, and it's not just the economic side of that as a rancher. And that's something that we're doing a much better job of in range lands. Like if we have collapse of range lands on these issues, it contributes to major wildfire problems, and we don't want natural disasters increasing into new areas. We don't need water shortages or, you know, disease vectors tied to ticks and West Nile virus associated with Eastern Red Cedar that we don't have as high of levels of when we have prairie. These things all affect systems and we were adapting we're trying to get out of our own success of last century tied to grazing, and add these additional elements and planning processes. We plan around our grazing really well today, some would argue. There's these other classes of problems that we need to expand upon if we're going to do those as well too. And annual invasives, woody encroachment, woody invasives, you know, those are two of our classic ones. Jeremy brought up bare ground, right. Like bare ground that's underneath a lot of forbs in grassland, right like that's great pheasant brooding habitat. That's great prairie chicken brooding habitat. There's a number of grassland birds and pollinators that require that type of vegetation. Well that's not what we worry about. We worry about large scale bare ground that lacks any of that component. So we didn't reconcile scale in these kinds of issues, we just universally manage against bare ground. And maybe we need to take a tip from grazing. We don't just exclude grazing or graze only one way, right. Like we manipulate how we graze around our objectives and local conditions and local context. This is I think there's some things and lessons learned of how we can apply that mentality to these other classes of problems.</p>

<p>>> I think one big question is that we have lots of areas, and you mentioned that whole cheatgrass challenge, southern Idaho, and quite a bit of the Columbia Basin in Washington are good examples of places where we do have pretty significant areas of plant communities that are now dominated by cheatgrass, some of which have sagebrush in the mix due to, you know, some success at fire suppression where you go without fire long enough that you have sagebrush that moves back in. But pretty large areas that have a lot of cheatgrass, and you know, other invasive forbs, and there's really, really high fire risk. You've got high fuel volumes. You've got high fuel continuity. You have a long period of time where fuel moisture is extremely low. What do we do in those places? Because we're saying restoration probably is not economically feasible there, but what do we do with them in order to prevent them from being a massive problem? You've opened up the idea or you know, put it back in front of us that these are seed sources for the places that are still intact, and that requires some attention. And then they're also obviously a source of fire, and therefore fire propagation into areas that are otherwise intact. What do we do with these dysfunctional ecosystems?</p>

<p>>> We hear this a lot when we talked about this concept and some angst from some managers who go well, that's great. But that's not my area. And the way that it's been articulated in our groups is like, it's the difference between an open and closed decision space. So for example, if your decision space is the entire state of Idaho, in other words, you're a statewide leader for your agency, and you make resource allocation decisions, can we direct resources to these cores that are still intact to prevent them from ever having a problem? You know, that would be where we prefer to place our first dollar under this strategy, right? And so you have options. But let's say you're a field office manager or a ranch manager in some of these places, like you just described, Tip, Columbia plateau, or the Snake River plain where we're never getting rid of cheatgrass. It's not eradication is not an option. So you have a more closed decision space. You work with what you have. And in those settings, you know we're now, of course, hopefully, at a larger scale. We're bringing some parity in our resource allocation to proactive management and healthy landscapes for the first time, which is not what we currently do, to match what we already invest in terms of fire rehabilitation resources. We probably spend a vast majority of our rehab resources in these areas with significant amount of cheatgrass in them already. And then there's other coping mechanisms. You know, I think about some of the work that Barry Perriman has done in Nevada and, you know, offseason grazing to kind of minimize that fuel load, and the thatch build up. We can actually manage fine fuels at a large scale with livestock. We can create these fuel breaks so that we're not having to deal with 100,000 acre fires. Maybe we can contain them at something smaller. These are landscapes where we should stop debating whether we're going to put the most pure strain of blue bunch wheat grass we have back on Snake River plain. We just need to stabilize that system and there's a variety of effective, competitive perennial grasses that would be better options than annual species. So again, this kind of goes back to different mindset, different expectations, different suite of tools than we would have in some of our more pristine and intact country.</p>

<p>>> But that's something I hadn't thought about. If you're able to seed 200 acres instead of 20 because you can buy $2 seed instead of $15 seed, you're saying this is the place to use a $2 seed just to get something down that's going to hold the site.</p>

<p>>> Yeah. So, you know, let's put it into an alternative seeded state. We'd call it that's maybe not our most desirable, you know, genetically appropriate native plants. But let's say resource that's limited already, we don't have an unlimited supply of it, and let's put that in the patch of 40 acres of cheatgrass that's in the middle of a core area, and let's keep that pristine and healthy. And so </p>

<p>>> You just need the plant functional and not back in the mix.</p>

<p>>> Right. So we're, again, going to learn to cope with cheatgrass; probably never get rid of it. But it can be better than what it is today and have fewer impacts on life and property.</p>

<p>>> Yeah. I tell you it's a great question that Tip's leading into here with like so we get this all the time. I mean, especially it was one of the interesting things. Everybody you know, it just makes so much sense. Like the earlier we act on big issues, the better off we're going to be. We want to prevent the big issues, and we can actually see and monitor with technology what those are. But not everybody can see themselves in the biome. In fact, very few do. So that's not really our profession. And so, no matter what you get like even in within the big intact areas, like oh. I just don't know where to start. But then you go into areas that are more severely infested and they're, you know, like you know, hey. Are we going to get left out? Right? Like what's the plan here? So we've actually, and this is happening across multiple areas and in rangelands now where we're just getting in the weeds on this a little bit. You zoom into those areas where we have trained ourselves right of looking at like we're looking at the heat of the wildfire; we're looking at the heat of the fire. And of course, there's somebody knowledgeable who's going, wait a minute. I'm trying to watch out for where new wildfires are going to spread. Everybody's looking at that wildfire. And this, you know, wise person is like, I'm trying to watch for new fires that are going to catch us by surprise and where it's going to go. That's kind of like this. We were looking at the heavy infestations and so forth, and like, oh man. What an eyesore. That's going be so much problems. We've never even had like, even in these heavily infested areas, where are the best spots? So we would zoom in to say like the Texas coastal prairie. And you can see the legacy of all the past work that's been done on the coastal prairie, which is one of the most converted and invaded prairie ecosystems in the world, and you can see this legacy of what's more intact and remaining. Well now that we know that, right, we could start taking the pressure off and actually start to figure out how to build back in the connectivity and scale and try and reduce more the exposure to these issues as part of our overall plan. And you start diversifying how you think about this. Right. Like you come up to grasslands, and regardless of the invasive species or anything else, and regardless of the stressor, you start thinking of how to work as a high functioning, right like that kind of thing. Like you've got the pit crew of NASCAR, and that pit crew is our agencies, right, and the landowners are the driver. We're wanting to be able to really support what those landowners are able to do as a vision. So landowner's sitting here going well, rather than everybody just trying to give us money for brush management, or to spray an annual invasive, if the NRCS is doing that, what could Pheasants Forever do over here? And Pheasants Forever is like well, there's going to be things that escape the initial treatment. So maybe we could come in the next year and do the mop up. Somebody else like, well wait a minute. We could put in money to do fuel breaks that are near the roads because that would help fire departments in the Great Plains because we won't have volatile Eastern red cedar fuels right on the road system. And landowners are looking at that when they see this mapped out and they're going, well you know, if we spent fuels money there, that would take some of the pressure off the interior. And so you start seeing how to leverage pools of money that are for different missions. Because in the end, what you're doing is you're managing the ecosystem. What we do right now is we have a single resource concern and we play Whac a Mole, and then there's another one, right, whereas in reality all of this is a context of how changes in our ecosystems are functioning. If we step back, you can actually spatially target and map different funding, different cost share, etc., to make it work as a machine instead of, I can only do one thing well. This is happening in Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Texas, on this kind of issue today, and I'm sure elsewhere. I mean, obviously it's happening elsewhere in the West, but we're just not alone in this. So if I'm also in these areas that I know are like Snake River, like well, I want to make sure that we're doing a better job of, you know, not just doing random fuels treatments as a fire ecologist. I want to put those where they're going to have the biggest benefit first and then go elsewhere. So, you know, right like that was the whole point of things like Firewise and then where to target grazing, where to start thinking about this. And we start working across different expertises to better manage our ecosystems. I think in three years, right, we're going to have multiple examples of this, where we start to see how to pool our resources better across agencies, landowners are collaborating and working together on these issues, and we start having models of success on how to scale this out regardless if you're heavily infested, right. We're not just living and accepting this. We can manipulate the land to offset, you know, some of the consequences and have the reality that we want. If you're more intact [inaudible], hey, we've got more of an opportunity to do something different. [Inaudible].</p>

<p>>> And by the way, this is the this is exactly how this is playing out in Idaho and in the cheatgrass challenge. You know, they are still spending ESNR resources on emergency stabilization and rehab seeding efforts following fire in some of these more heavily impacted areas. They have strategic networks of fuel breaks all across the Snake River plain that are being installed across land ownerships. And now with this, you know, effort to recognize proactive management through the cheatgrass challenge, NRCS, Fish and Wildlife, the governor's office, BLM, Forest Service, they're all starting to now incentivize and fund projects in places that wouldn't have got any attention before like the Lehigh [assumed spelling] Valley or something that's just got a few early invasions of cheatgrass and they're trying to get on it. Well, now they've become elevated in their priority. And so that's a different pot of funds. Like Dirac's talking about, this kind of whole landscape approach, but we're putting on par these places that maybe we would have put on the backburner previously.</p>

<p>>> Yeah. And I can't resist saying that that landscape approach, working across land ownerships requires communication by the individuals who are responsible for managing those land ownerships. And it's perhaps not accidental that the Society for Range Management is having their annual meeting in Boise, and the title of the meeting is Range Lands Without Borders, with this idea that you know, most of the organisms, apart from humans, don't observe these legal boundaries, and if we don't make efforts to manage across them, we're likely to not be successful. And the meeting I mentioned is in Boise. This is one of the main places where this needs to be done and perhaps is beginning to be done now. But it requires as you mentioned, it requires both working across knowledge domains as well as working across, you know, social barriers, you know, where there might be more difference between a range land ecologist and a wildlife biologist than there is between, you know, people that maybe have different skin colors for example.</p>

<p>>> Yeah. We like to say, "all hands all lands" because that's really what's going to, it's going to take to stabilize ecosystems that are already in turmoil, and then maybe prevent and save for future generations the ones that haven't fully transitioned yet. << What a great point too. I mean, right like range lands especially, you know, thinking about it from that borders comment and a private side. I mean, driving around as an example in Texas, I mean, you have like these big gates in areas that lead into, you know, a ranch and a house that you can't see off in the distance, but, you know, it's kind of like, ooh. That's a gate and a border. And there's kind of this perception that you know, hey. This is private land, right? Stay off it. And so it reinforces this idea of, hey. We're here to support if you ask us, but we're really considerate and sensitive to the feelings of private landowners on rangelands. And what we're seeing nowadays on these bigger issues of annual invasives and woody encroachment and so forth is that take the heavy infested areas and everything else, our current model forces a bit of this. Well, here you go. Here's money for it as part of a cost share program or anything else, and here's your errand. You know, meanwhile, professors and academics, we're training people on, you know, small university properties, right, or like the these kind of, you know, training areas and so forth. We don't really have like a scale of ranches. So people get trained on smaller areas and we look at our feet, and meanwhile, ranchers are trained at this, you know, larger landscape scale because they're managing the ranch. And unless you grew up as a rancher, you don't get that experience coming into range lands. And then you get a job and, you know, all right. it's like, we're not Ooh, I don't want to you know, I want to be sensitive to the private properties issues. And when I talk to ranchers today on this they're, hey, if we as we plan and we do this like if somebody came in, and we're willing you know, you put all this money into the initial treatment and else and 5% of what we were managing escaped that, would you open the gates to let a group come in and search and destroy and take it out? And they're like you know, some would be like, well. It would depend on who it is, right? Is it, you know, the grandson of my neighbor? Sure. Is it some stranger? Aah, I don't know yet. And others are like, absolutely. This isn't 1980s rangeland. We need the help. I'm a rancher by myself and I'm asked to do everything. Prevent endangered species. Prevent the wildfire issue, and I'm just trying to make a living. I guess it's reinforcing that point, there's opportunities to work without boundaries today and support the vision of, you know, range lands being more intact, and the same is true the more infested you get. What we shouldn't do in infested areas and we shouldn't do in intact areas or anything in between is just keep saying, you know what? Ranchers make a living on their land. It's all on you to manage all ecosystem services by yourself. So that's where I'd like to see our profession create more of a supporting workforce given all the additional values we get off of range land and a lot of which is private because there's a lot of local ranchers that are like yes, as long as it's under their vision, their guidance, so forth. We're working as teams now, and we can start to build that out going forward. So maybe there's opportunities we haven't explored in that, but we're not going to it's hard to do really expensive restorations or work at these scales on these issues and say, yep. Those 40,000 acres. That's one rancher's family. Good luck.</p>

<p>>> Right. I think you're right that there are beginning to be more proactive social structures that work across those borders. And we've seen that in the negative in that at least in quite a few states of the West, we have weed boards that have, in recognition of the fact that problem plants don't observe these boundaries, the employees of the weed boards have the authority to cross onto private property, and actually to take action against weeds on private property, or to do it and then send you the bill because it does affect your neighbors. And I think it's encouraging to see some of these more proactive efforts that see that as an opportunity to work across boundaries instead of applying punitive measures across boundaries.</p>

<p>>> Yeah. You all have seen the same thing we have. Even when we plan interestingly in some of our areas where we do have this kind of structure developing, wherever the lines are on the map, right, of like, oh. Here's this one planning zone or district, you can actually see for things that are invasive species, they that border ends up being the weak point in our overall plan, just because we were trying to delineate, you know, a place on the map. And so if there's a weakness there, it takes advantage of it. So we've started identifying lines on a map as, hey. Do we have a plan for that too? You know, rather than both sides looking over the fence at each other going, like wait. Whose responsibility was it?</p>

<p>>> Well I'm a little bit short on savvy ideas for how to switch us over to a closing here, but there are there are going to be a lot of listeners that don't receive or read the range lands journal and for those that don't, where could they read more about this Defend the Core strategy and ideas on how to manage in each of these different zones that we've talked about?</p>

<p>>> Yeah. We've got some great resources Tip. If folks visit our Working Lands for Wildlife, wlfw.org, and search for Defend the Core blog articles. We've got a couple that are posted through our, I guess our sage grouse for the sagebrush ecosystem in our lesser prairie chicken site on the plains. But [inaudible] and I kind of gave the same interview, story for both of these biomes on how this concept's being applied to address invasive annual grasses and [inaudible] country and woody encroachment in the Great Plains grassland. That's a great digestible way to find out about it. What really excites all of us is we're seeing you know, this concept is hard to argue with; I think people get it. I've not had one person say, no. This doesn't make sense. It makes sense. And people are taking and running with it in other circles as well. We've got the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies just published their sagebrush conservation design report that looks at the state of our sagebrush range lands over the last 20 years and embedded in that is a Defend the Core framework for managing these ecosystem threats. Similarly, out in Dirac's country, there's a whole suite of conservation partners and central grasslands roadmap partnership that's taken these same maps, these same ideas and embedding them within a broader partnership conservation network. And so people are going to start seeing these strategies embedded in how people are doing business. We're really excited about it, and we have a lot to learn. I mean, we're still, admittedly, humble about what we don't know. And we're trying but what we know is that what we're doing isn't working. As we started the podcast, when you look at the whole of rangelands, we're losing them, and so we have to have to do something bold and different. And I think we're going back to the principles of invasion ecology, landscape ecology, and early detection, rapid response, you know, trying to get on these issues early, giving ourselves the best chance to be effective.</p>

<p>>> Yeah, I've been encouraged by what I've seen and heard so far. I feel like some of the biggest benefit is for landowners, potentially landowners of large holdings that care, but they feel like it's bigger than I can get my arms around, and I'm not sure what to do and where, and then how to pay for it. And I think this provides some direction for specifically, what do I do if I have this situation? I think that is some really, really useful direction, at least in context where I'm familiar with. You know, these same problems and landowners that have some money to deploy but aren't quite sure where to do it, I think this is providing some really good direction to both Defend the Core, grow the core, and try to minimize damage.</p>

<p>>> Yeah, I have to say, you know, we talk with these bigger scales, right, because that's where we were, in thinking have the luxury with, "open decision space" to prioritize. But if you're a rancher, a land manager, and you're working at the scale of a pasture and allotment, all of these concepts are scalable. And so, you don't even necessarily need space, you know, special tools or mats. Your perspective on the ground and your knowledge of what is there, you can start to map out, well where are the core areas within my passion? If I were to start doing something, at least anchor yourself in an area that's intact, and then move out from there. I think the same concepts still apply.</p>

<p>>> Yeah. So that's a really key point. And Jeremy mentioned I mean, I think where are you going to find more information and see this? It's emerging and coming out all over, and that's when, you know, that maybe you're onto something is because it's being shared and owned by multiple different badges and entities and organizations. And that includes you know, we're seeing it owned and messaged by the industry. You know, so there's actual policy change from groups like National Cattlemen's Beef Association, and you have the emergence of this, and extension where you have a launch this year of a Great Plains Grassland Biome Extension Partnership. We're actually sharing the similar terminology across states, and then talking about how do we embed that into, you know, more county extension efforts that have maybe even like local cattlemen affiliates and so forth here. That is where this is currently at, and it's starting to scale from, you know, what we tend to do locally on our pasture, on our allotment, and maybe with our neighbors in an area to what's being talked about broadly, nationally. And so I think people are going to see that in a diversity of ways, and all of them going like, oh. I didn't know where - yeah. You heard about the same thing? They're going to hear it from different messengers, different places. It just sends a better philosophy of how we can attack this issue. And, you know, that's what we can look forward to, I think, a little bit more in 2023.</p>

<p>>> I would agree. I had been personally encouraged by it and have been impressed with what I've read and seen, and I've also heard this coming back at me from a few different directions. So I'll say thank you very much for what you all have been doing, and we'll see what we can do to promote these ideas. Thanks for your time today, guys.</p>

<p>>> Thanks. Thanks to you, Tip. It's been a blast.</p>

<p>>> Yeah. It's been great. Thanks Tip.</p>

<p>>> Thank you for listening to the Art of Range podcast. You can subscribe to and review the show through iTunes or your favorite podcasting app so you never miss an episode. Just search for Art of Range. If you have questions or comments for us to address in a future episode, send an email to show at artofrange.com. For articles and links to resources mentioned in the podcast, please see the show notes at artofrange.com. Listener feedback is important to the success of our mission empowering the range line managers. Please take a moment to fill out a brief survey at artofrange.com. This podcast is produced by Connors Communications in the College of Agricultural, Human and Natural Resource Sciences at Washington State University. The project is supported by the University of Arizona and funded by the Western Centre for Risk Management Education through the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture.</p>

<p>>> The views thoughts and opinions expressed by guests of this podcast are their own and does not imply Washington State University's endorsement.</p>

<p>[ Music ]</p>

<p> </p>

<p> </p>

Rangelands journal special issue, "Changing with the range: Striving for ecosystem resilience in the age of invasive annual grasses".

SGI blog on invasive annuals in sagebrush country: https://www.sagegrouseinitiative.com/defend-the-core-fighting-back-against-rangeland-invaders-in-sagebrush-country/

LPCI blog on Woody encroachment in grasslands: https://www.lpcinitiative.org/defend-the-core-fighting-back-against-woody-invaders-on-the-great-plains/

NRCS WLFW Frameworks for Conservation Action: https://www.wlfw.org/

WAFWA Sagebrush Conservation Design: https://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2022/1081/ofr20221081.pdf

Western Governors Association Toolkit for Invasive Annual Grass Management: https://westgov.org/images/editor/FINAL_Cheatgrass_Toolkit_July_2020.pdf

Idaho Cheatgrass Challenge: https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/programs-initiatives/eqip-environmental-quality-incentives/idaho/the-cheatgrass-challenge-idaho

Kansas Great Plains Grassland Initiative: https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/conservation-basics/conservation-by-state/kansas/ks-great-plains-grassland-initiative

Guide for Reducing Woody Encroachment in Grasslands: https://www.wlfw.org/assets/greatPlainsMaterials/E-1054WoodyEncroachment.pdf

NCBA Cattlemen to Cattlemen episode on defending the core: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EpsJnM-IrPY