Cattle growth goals and livestock use of large, topographically challenging landscapes have been at odds for some decades. Weaning weights went up, cow weights went up, and herd distribution on rangelands went down. Dr. Jim Sprinkle, an Extension beef specialist at the University of Idaho, has been doing research that is providing guidance on developing cows that do both, leading to herds that are more efficient on feed and graze hillsides -- the Perfect Range Cow. This has significant implications for reducing land use conflicts, particularly with riparian grazing concerns on public lands, but also profitability and sustainability of range livestock operations.

The Art of Range Podcast is supported by the Idaho Rangeland Resources Commission; Vence, a subsidiary of Merck Animal Health; and the Western Extension Risk Management Education Center.

Music by Lewis Roise.

Transcript

[ Music ]

>> Tip Hudson: Welcome to "The Art of Range," a podcast focused on rangelands and the people who manage them. I'm your host Tip Hudson, range and livestock specialist with Washington State University extension. The goal of this podcast is education and conservation through conversation. Find us online at artofrange.com. Welcome back to "The Art of Range." My guests today are Jim Sprinkle and Steve Steubner. Jim is the University of Idaho's extension beef specialist stationed at the research facility near Salmon, Idaho. And Steve is a repeat guest as the journalistic brains behind the Idaho rangeland resource commissions life on the range series. Jim and Steve, welcome.

>> Jim Sprinkle: Hello.

>> Steve Steubner: Good morning.

>> Tip Hudson: We're here to talk about the newest piece in the life on the range series that was just published a few weeks ago titled "Searching for the Perfect Range Cow." For listeners who are maybe here for the first time the life on the range project is short videos paired with articles that bring rangeland grazing research and innovative management to life. The perfect range cow is an intriguing name and it seems to imply something of a claim. I mean just the words perfect or ideal range cow bring to mind a lot of related ideas from animal terrain use to nutritional efficiency to grazing behavior to diet selection. And I'm not a nutritionist so I expect you could make an even longer list than I could on what would make for the perfect range cow. But this is interesting. The concept of an ideal range cow and their range of possible meanings behind that almost feels like the ideal range research project. It seems like the question would need to be tackled by the ideal range researcher. Jim, I know you're too humble to claim that title, but we'll let listeners decide whether or not the moniker fits. So with that royal introduction Jim I don't remember that much about your background. We've sort of been two ships passing in the night in the same social spheres for the last 20 years, but haven't done that much together. I know you were a horse trainer at one time. But I don't know much about your trajectory before or after that or I've forgotten. Memory's the second thing to go. So tell me a bit about how you got in to horse training and then got in to range work.

>> Jim Sprinkle: I grew up on a sheep and beef cattle operation in southwestern Virginia, mountain and valley region of Virginia. And we -- so I got interested in horses when I was about 18, got my first horse to break and started breaking a lot of horses for people in the community. And then I went to Ricks College to the horsemanship and stable management school that they had at that time. That's now BYU Idaho. It's a four year institution now. It was a two year when I went. And I stayed in the horse business about eight years and finally starved out and decided I had to do something different. So I was 33 years old and we had four children and we went back to school and I went to BYU and went through the animal science program. And then -- and then after I graduated there in 1990 I went over to Montana State University and just worked with a magnificent advisor Dr. Don Chris [assumed spelling] and we were looking at forage intake on different biological types of cattle throughout a year. And I remember just one thing that he said to me one day. I was talking to him about some lab procedures and he said, "Well, how do you know that works?" And so I had to go and find the laws that governed the analysis that we were doing and present that to him. And I think he knew, but he wanted me to know. So that's the kind of person he was. And then from there I went to Texas A&M University. I decided that if I could get my PhD without having to borrow more money and then if I could also work with some different breed types in a range setting then I would pursue that. And so I went to the Uvalde experiment station and Bill Holloway was my major advisor. And we looked at different heat adapted cattle and how they adapted their grazing behavior and their forage intake to the different environments that they were exposed to. We had Angus from an Angus and then we had Tuli Angus which is a heat adapted bos taurus breed from Africa. And then we also had a joint project with play center Nebraska, the lead animal research center, looking at how energy is partitioned differently with different breed types. And so I worked. So I got through with that and then I went to work as an extension -- area extension agent in Arizona and was in a central part of the state. We covered kind of the northeast central region. And was there 20 years and worked a lot in range and range livestock production. And enjoyed my time there. And then I retired from that and I came up to Idaho in 2015 and had an opportunity to come here to Salmon and the job was just pretty intriguing to me. We had -- we were on the cusp of acquiring a long term lease on a range unit down by Hailey Idaho near Sun Valley. And that's where a fair bit of this research has taken place. And we also -- they were evaluating all the replacement heifers for feed efficiency with these growth seg units. It's now [inaudible] is the name of the company now, but basically the animals it records all the day long. There's a RFID tag on them like at the grocery store. Whenever they go in to eat that records how much they eat. And then they're compared to each other and animals that eat more than are expected based on their weight and their level of production are inefficient, termed inefficient, and they would be -- have intake at least a half a standard deviation above the average. And those that eat less than expected would be termed as efficient and then I decided we wanted to look at those animals out on range and that's kind of my background. If you've got any questions about that, be glad to answer them.

>> Tip Hudson: No. That's great. So this is about 30 years post PhD working on various stuff in Arizona and Idaho. The papers that you sent over and this project kind of sound like the culmination of a career's worth of research and real world observation. Does it feel like that?

>> Jim Sprinkle: Yeah. It's been very satisfying. And you talked about the real world and that's why I like working in extension. I feel like I have one foot in academia and one foot out in the real world working with clientele doing some of our applied research. And, you know, it's harder to do that applied research nowadays. It's harder to get the money. But pretty satisfying when you can.

>> Tip Hudson: Yeah. Let's come right back to that. Steve, I'm curious. A lot of times this sort of research stays a little bit under the radar. You know, it gets published in animal science journals and range journals, but it doesn't always make it out. How did this come to your attention?

>> Steve Steubner: Well, good question. I've known Jim for quite some time and we've worked on a number of stories over the years. And so we just stay in touch and see each other frequently. And I just might add on Jim's research work I mean he just does exceptional exemplary research in my opinion. And really enjoys digging in to, you know, current issues and solving problems. And I think that's what the University of Idaho extension tries to do. And Jim really helps them deliver on that. And so anyway gosh I think it was almost four years ago when we first were visiting about the research and Jim talked to me about it and then he said, "Let's meet out at Rock Creek and we're going to start next year and put the GPS collars on the cattle as well as the accelerometers on each collar." So we showed up for when they were putting the collars on and just getting started with the research and also with his grad student. And anyway so we did a bunch of shooting then and then just kind of I think I had millions points of data to go through over the years. But, you know, it's ultimately they identified the G marker for hill climbing cattle and cattle that especially are going to climb hills naturally in a range setting when it gets during the hottest days of the summer. And so that was really the upshot. And super interesting and has major implications for range management.

>> Tip Hudson: Yeah. You guys introduced a video by announcing that this research team, your team, has identified a genetic marker for animals that will climb hills instead of staying in the bottoms. And Sergio Arispe said in the video that we're at the forefront of understanding cattle behavior. But studying cattle behavior is not new. You know, you read stuff from 100 years ago on range ecology and it sounds like it could have been written yesterday. I think I ran across a forestry proceedings publication from 1914. It was like a big research gathering in the aftermath of those big fires in northern Idaho. I think 1910 that they called the big blow up or the big burn. It was like 3 million acres. But the description of the concepts around wildfire behavior, research needs, you know potential large scale management actions like fine fuels reductions, it sounded so modern I had to go back and look at the date again to make sure I was reading what I thought I was reading. So I'm not disputing Sergio's comment because I think I really do think that there are things that we can quantify now at landscape scales that we couldn't before like collecting accelerometer and GPS data on every cow in a herd on a complex landscape. So yeah. Let's go back to the title. What do you mean by the perfect range cow, Jim? And what is different about our ability to research this today in 2025 compared to 1925?

>> Jim Sprinkle: Yeah. So I will echo what you said about grazing behavior research has been occurring for quite some time. I've got a picture on my computer from 1936 of some grazing behavior research that was done at the center reader experimental station down south of Tucson, Arizona. And it's got a picture of an old 1930s pickup truck and there's a guy in it with a pair of binoculars and there's big numbers on the side of one of the cows that he's looking at. And so yeah. We've been looking at it for a while, but I think the -- and I've done some of that old type research. I've in my PhD project we had people sitting up in deer towers observing cattle all day long with a clipboard and writing down everything they were doing every five minutes. So that type of research is very tedious and hard to get to. And of course the advantage we have nowadays is we've got some modern technology to assist us in getting just a lot more data. So for instance, you know, the GPS. People have been using those since the 1980s and we can dial down. Some people are dialing down every minute or two on where the cows are located. And so that's useful information. And we can look at rate of travel and kind of make some extrapolations, but the GPS will tell us where they're at. The accelerometer will tell us what they're doing while they're there. And the accelerometers started being used, oh, late 1990s. And then they came in to the 2000s. And when I started working with them they -- there wasn't much in the literature to help guide what we were doing. So I kind of fumbled around in the dark and finally found some methodologies that ultimately were similar to what a lot of the other scientists were using. So an accelerometer is a device used on a rocket and it measures velocity in three directions, up and down, side to side, and backward and forward. And so you can pair that with head movement on cattle and you can get some distinct signals of what they're doing if you have some observed data to calibrate it. So we get on our accelerometers we get 25 measurements per second. And we average that down to every five seconds. But we get a lot of data every day. And so anyway the thing that I would say about this ideal cow is that on many western rangelands I think we need athletes out there. Animals that will climb and have the physiological capability to get out of the bottoms and not heavily impact riparian areas. And, you know, you go out on a ranch. I remember being out on a ranch in Arizona and we saw this cow way on a hill top and I told the rancher, "You need to get that cow's number and keep replacements out of her because she's doing what some of the others aren't." So I'll just stop there and see if there's any questions.

>> Tip Hudson: Yeah. I think -- I think this would be a good place to discuss some of the implications or why does it matter. You know, you've been around big western rangelands your entire career observing and studying cattle behavior, measuring the effects with monitoring methods. I think that's some of the first stuff that I saw with your name on it was some monitoring publications from Arizona. You know, how ranchers should interact with [inaudible] processes and but this -- you know, you can have tens of thousands of acres of perfect upland grazing that are jeopardized because of overuse in the riparian area. Is that one of the -- I feel like that's one of the motivations, but that's more like a -- that's not necessarily production or profit related. That has more to do with protecting ecosystem function. And one of the reasons why I think this is sort of a perfect range research study is that it really encompasses all of that. But, you know, take just a minute to describe, you know, what you think the implications are of this just in terms of riparian grazing.

>> Jim Sprinkle: Well, yeah. I mean, as you mentioned, we've got a lot of these big allotments. They might have a 3 to 5,000 acre pasture. And so there's a lot of country that cows could use and they could stay in there for a while. But it might have a live stream going through it and there might be some fish in that stream that are of concern. And so if you can't keep the cattle out of the riparian area than that's what's going to determine when you have to move, if the cattle are -- take the stubble down below what the recommendations are, the guidelines from the land management agency.

>> Tip Hudson: Right. Even if you barely touched the rest of it.

>> Jim Sprinkle: Yeah. And so, you know, grazing distribution is something that we've been talking about a long time. And we've -- we've found some things with these efficient cows that I think are worth looking at. Maybe not as a sole criteria for selecting replacements, but as something you should look at. And I just want to mention, and I think it's in the video that the state produced, when I started this research I thought we would want inefficient animals out there on rangeland because they, the inefficient animals that eat more, they have more appetite. And so I thought we'd want to have animals that would have the appetite and the drive to get out and work. So the idea is that the inefficient cow is more motivated to go on a more aggressive search for food.

>> Tip Hudson: Yeah. That's what I thought.

>> Jim Sprinkle: Yeah. And that's the beauty of science. That got turned completely on its head. I was wrong in that assumption. The -- we found in every study we've done, and in the literature you can find a lot of other studies that say that efficient and inefficient animals graze differently. Now if you have good climatic conditions, the temperatures are moderate and, you know, you're looking at 60s or 70s, sure those inefficient animals they'll go out and graze longer. But once you get in to a heat stretch situation, say in Idaho, that's when it gets up to 79 or 80 degrees Fahrenheit, then those inefficient animals they tend to stay more down in the bottoms and they don't get up and cover that high ground like those efficient animals do. And there's a physiological reason for that. And so what it is is what I like to compare it to is the difference between say a small block engine, say a, you know, V6 or an air cooled engine, and like comparing that to the efficient animal to a hot rod engine like in the 70s muscle car. So those animals that have greater appetite they have bigger internal organs. They have a bigger gastrointestinal tract. And that takes a lot of energy, but it also produces a lot of heat. So those animals that have the big appetite and the big GI tract they are at an advantage when it's cold out there and say you're looking at 20 below 0. But once you get in to a hot situation it has an impact on them. And there's a difference in how those animals graze too. The efficient animals they tend to be more purposeful about how they graze. They just put their head down, get it done. The inefficient animals because they're after more nutrients they do a lot more search grazing. They do more walking than do the efficient animals. They meander more as they graze. So that's an energy cost.

>> Steve Steubner: The weight gain, just to jump in, Jim and Tip, the weight gain is the same for both. And so you have these more athletic cows that are using the range better are still ending up with the same weight gain as the inefficient cattle that are lying down in the bottom of the crick.

>> Tip Hudson: Yeah. That's good. It makes sense of the term efficient versus inefficient as opposed to just there being a linear relationship with body size. So what I'm hearing is that this response to heat stress is not just related to body size. There are other physiological factors that predispose the animal toward that behavior.

>> Jim Sprinkle: Yeah. They've looked at -- they've done some research with feedlot animals which are not the same as grazing animals, but those efficient animals they appear to be more efficient in protein turn over. You know, and that's an energy costly system replacing tissue. There's a difference in what we talked about, the heat of fermentation. We discussed that. They suggested there may be some difference in digestibility. So there's just a lot of advantages to those animals and you might have when you're looking at efficient versus inefficient animals -- you could have an animal that weighed 200 pounds less than another animal that would eat just as much or more than the efficient animal. An inefficient animal 200 pounds less could eat more than an efficient animal that actually weighed more. We first -- our first study that we did was over at the sheep station in Dubois and we just turned out some efficient, inefficient, and average three year old cows. They were part of -- they're becoming three year old cows. They were part of the herd. And they were out on the late season dormant range and nobody got any protein supplement. So everybody was losing weight. And those efficient animals lost 1.4 pounds per day and the inefficient animals lost 1.9 pounds per day. So they just was that cued us in to there's some metabolic differences there that persist out on rangeland.

>> Steve Steubner: Just going back to the use of the range, Scott Jenson had a number of great comments in our video which I thought were, you know, very appropriate. He was really encouraging, you know, range ranchers to take a look at this because it should improve the overall use of their range which would benefit them, you know, in terms of the relationship with [inaudible] service state department of lands, whatever. And so I thought that was super significant. And, you know, conservation groups that are looking for those kinds of results I think will be happy to see it as well. And Jim had said I think this genetic marker does appear not only -- these were Angus cattle at Rock Creek, I believe. But, you know, you could also find the same genetic marker in Herefords or even dairy cows.

>> Jim Sprinkle: Yeah. Maybe I'll jump in on that. So the markers we found we found five markers related to grazing behavior. And we didn't have large enough numbers to specifically relate them to efficient versus inefficient animals. But I think there's some correlations there and with more of our DNA as we analyze it I think we may find more of a relationship. We're not the only one that's found this. Dr. Derek Bailey works with New Mexico State and he's retired now. He did a joint project with Colorado State and they looked at herds all over the west. And they have found genetic markers for hill climbing cattle. And they have also seen some type of relationship with the efficient versus inefficient animals.

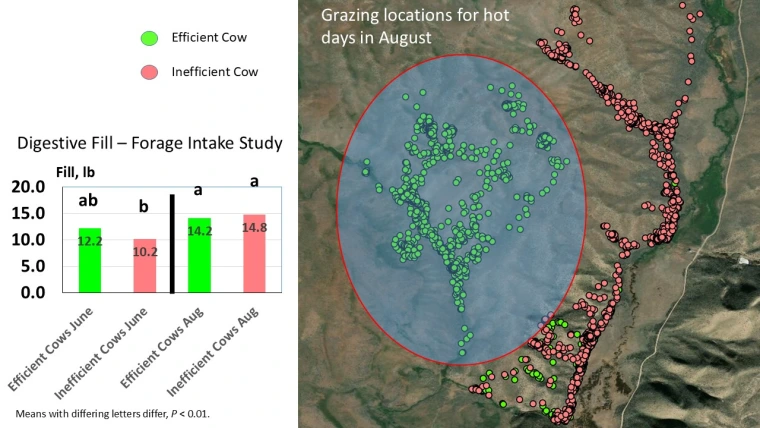

>> Tip Hudson: Yeah. And the results are pretty dramatic, at least the -- you know, some of the pieces that you can pull out to compare one to another, one cow's behavior to another. Really dramatic. And there's a good graphic in the life on the range article, the website that we'll link to in the show notes, but it's showing one animal's distribution over the hot season of the year, you know, where the animal is all up on the hill sides, and another animal represented by a different color that shows where she spent all of her time during that I think it was May through August and it was literally all on the creek. And there's almost no overlap in their locations except for where it looked like maybe they got turned out even though they're in the same grazing unit, the same pasture. How were those two cows different from each other? Or was that graphic showing kind of an amalgamation of multiple cows? Describe the graphic and we might be able to put that one on the episode page too.

>> Jim Sprinkle: Yeah. It's not describing an extreme. It's describing two animals that are representative of their groups. And as you know if you go to showing all the GPS locations for all the cows in the herd you just get a big blob. So we had to choose one animal that represented each group. And so those differences we don't see those show up until you start getting in to that thermal heat load, the mild heat stress. And so that graphic that you'll have in the show notes shows one animal that, as you said, spent a lot of her time down lower in the pasture, and the other animal was traversing more of the slopes because they don't have the heat load. And so the other thing we've found is not only do we find that difference in where they go. We found the difference in when they get up to start grazing in the afternoon. So for instance when the temperatures are mild in the spring we had a five or six day stretch where those inefficient animals grazed 1.7 hours longer each day because of their appetite. But as soon as you get in to a heat stress situation they can't. They have to lay down and dissipate some of that heat load that they have. And so that doesn't hold true anymore. In fact the efficient animals on several of those hot days will be spending more time grazing than the inefficient animals. And the other thing is the efficient animals will get up earlier in the afternoon, say for instance they get up at 3 o'clock in the afternoon, and start grazing. The inefficient animals they stay there longer until it cools down more and then they get up and start grazing.

>> Tip Hudson: So were those animals different weights? Did they have different body sizes?

>> Jim Sprinkle: The animals in our study there's been no difference in calf weights. There's been no difference in cow weights. There's not been no difference in body conditions score unless you deprive them like that once they talked about in Dubois.

>> Steve Steubner: Yeah.

>> Jim Sprinkle: And so the calf weights are the same. The milk production's the same. The -- it's just -- it's just that those efficient animals tend to use the nutrients a little more efficiently and they don't have some of the negative heat stress situation. Can I make another comment here? So my graduate student, PhD student that was on this project, Landon Sullivan, he's in Texas. Works for extension. Still working on his degree. He wanted to test using an injectable trace mineral that has four of the minerals that are related to regulatory mechanisms, particularly heat stress. And he wanted to inject some of the herd with that and see if it made a difference. And we -- it's not really mentioned in the video, but we have seen that those inefficient animals if they get -- got the injectable mineral twice in the summer it kind of mitigated some of those negative effects and their behavior became more similar to the efficient animals.

>> Tip Hudson: Steve, what were you going to say?

>> Steve Steubner: Oh just that I just think it's fascinating that, you know, ultimately the weight gains are the same. You know? And I mean that's obviously a very important point from the rancher perspective in terms of, you know, when they're shipping cattle to the market and how much money they make. So anyway very interesting.

>> Tip Hudson: Yeah. Jim, just a couple more questions on the heat load. You mentioned -- I can't remember if it's in the article or not, but one of the papers talks about the temperature humidity index as a way of quantifying heat load. So what I'm wondering about is is the -- is that index different at different positions on the terrain? Like do you have more air movement up on the hill slope compared to riparian, but the riparian area has shade and greener grass? And then define or maybe start by defining the heat index. How does that -- how does it work?

>> Jim Sprinkle: Yeah. It's a -- the thermal heat index is a calculation that we've been using in heat stress type research for many years. And it's very reliable. It takes in to the ambient temperature and also the humidity and for instance out west we don't have much humidity. So maybe our cattle can tolerate a little bit higher temperatures than they would if they were back east. But and ice. It's almost like a switch. I tell you the two values that we have is the numerical values of when an animal's in mild heat stress it's at a temperature humidity index of 72. And that's combined over those values. That's not the temperature value. And then when they move in to severe heat stress it's at 79. And you can -- you can just see those cows out on the landscape. As soon as they hit that mild heat stress you'll just see the behavior start to change immediately.

>> Tip Hudson: So it's like a threshold. This was one of my questions. Does the behavior change like linearly following the progression of the index or does it -- it sounds like you're saying it switches at that threshold.

>> Jim Sprinkle: Yeah. It's kind of abrupt. I mean you just see it immediately. And here's something that we discovered. Okay? We were looking at our data and we were looking at the travel distances that we had with the cattle. And so on July the 19th of 2022 the cows got up and started traveling a lot. And so they instead of traveling like 2 and a half miles during a typical day some of those cows traveled 13 miles. They went from one side of the mountain to the other side of the mountain and back. And so I thought at first we had a predator that had got in there. So well no my first thought was well maybe the cowboys moved them. So I checked with our cattle manager. He said, "No. We didn't move them that day." And so then we got to thinking about predators and we have some cameras scattered around the pasture that they're doing for some recreation study. And there was no -- I asked some of the interns to look at those photos. There was no predator activity. They said they just saw a cow [inaudible]. But what they did see was the day preceding that big move the wind started coming up. And so we had wind that was 20/30 miles an hour that averaged about 12 miles an hour. And so it just relieved a lot of that heat load and so what happened was that those animals traveled more and the inefficient animals they traveled about 2 and a half miles more per day than did the efficient animals. And they spent almost five hours walking compared to about three hours for the efficient animals. And so it explained that those animals have the desire to get out and harvest nutrients. And so they were just tamped down on by that heat load. As soon as that wind came up it took away that heat load and they started trying to harvest more nutrients. Now the day after that the calves out of those inefficient cows that had to follow their moms they were 290 meters away from the cows on average over the day. And the efficient -- the calves from the efficient cows were about -- were less than 1 meter distant from the cows. So big difference. Big difference. And so yeah. They like down in Arizona we had a lot of our ridge tops would be where cows would go to try to catch the wind during the summer. And, you know, that's -- I don't know what I can tell you more about that. So I'll just stop there.

>> Steve Steubner: I got a question for Jim, Tip.

>> Tip Hudson: Yeah. Go ahead.

>> Steve Steubner: I was just curious after our story and video have come out whether you've had some inquiries from folks and what kind of feedback you've had so far.

>> Jim Sprinkle: Well, you were there in the meeting when that video was shown and that's the main interaction I've had. I've had -- I've had comments and inquiries from the past based on other stories and podcasts that have occurred. We had one podcast that they did on the working ranch radio show and I had a couple of people from different parts of the U.S inquire. I've had people from Wyoming and different places inquire about a research. We had a rancher down in Arizona that has followed some of this research and he asked me to come down in April and the last -- in April 2025 and present to their buyers at their bull sale. And so we -- I came down and there was about 200 people there. So people are fascinated by this of course and probably had 20 minutes of questions after the presentation.

>> Steve Steubner: Cool.

>> Tip Hudson: That teed up my next question. Just to play the devil's advocate, there's a -- you know, dozens of things a rancher might want to select for in cows and bulls. You know, attributes of all kinds that are heritable. Disposition. Milking ability. [Inaudible] resistance to flies. Breed back efficiency on vegetation. You know, on and on and on. And some of those things might be antagonistic to each other. But I think that's -- it sounds like that's part of what you're getting at in calling this the perfect range cow because you've got to balance all those things. You want a cow that will protect a calf, but you don't want fence jumpers or dog stompers. I would guess the fence jumper might also be the hill climber, but this -- yeah. So I have I think historically associated the hill climbing behavior a little bit more with disposition and not so much with physiology. So this is really good news. But the devil's advocate, you know, question is there's a million things you can select for. Why this one?

>> Jim Sprinkle: Yeah. I agree with you. So we don't recommend single trait selection. You have a variety of things you want to look at. And some, you know, in the past -- some people have tried to balance some of these multiple trait selection criteria with indexes where they have say a weight applied to four or five traits that they're trying to look at. But I think there's some things here. So maybe if I just talk about overall efficiency we've been chasing weaning weights for 30 years now and we've been very successful.

>> Tip Hudson: At increasing them.

>> Jim Sprinkle: In increasing them. So weaning weights now are probably a couple hundred pounds or at least 150 above what they were back 20 or 30 years ago.

>> Tip Hudson: Wow.

>> Jim Sprinkle: But at the same time we've increased cow size and we've increased milk production. And so, you know, if you're going to have heavier calves you're going to have more milk production. So that's a very costly thing to support on rangeland. I have looked at for instance milk EPDs and to fit on rangeland there's about 5% of the breed, the Angus breed, that will kind of fits a rangeland setting. So it's hard to select those animals. So but there's some things we can do. So I really recommend that people frame score their heifers when they select them. And you can just put some marks on the chute with a Sharpie and just look at the height of -- hip height of the animal. And you can decide what frame score she is. And so if we can keep those cows down to a frame score 5 or 6, you know, that's about 1,150 to 1,250 pound cow. And if we can keep the milk production down by selecting that that will help get more of these cows pregnant. But then at the same time we could actually in time have some markers that we could select for hill climbing ability. Then we could get an animal that not only is well adapted to the range situation, but maybe one that would lower our feed costs 15% a year on that 1 cow and would encourage her to use more of the landscape.

>> Steve Steubner: Well said.

>> Tip Hudson: Yeah. Yeah that's - that's tremendous. I think that's a good place to wrap that up. I've got just a couple more questions that I think you're in a good position to answer as I think one of these rare people that has sort of spanned the world of rangeland ecology and animal nutrition. I think there used to be more of those maybe, but there's not. And I've said before one of my regrets is that I did not get more, you know, formal instruction in animal nutrition when I was in college. But, you know, sort of putting all these things together I'm curious if you were -- yeah. To put your thinking cap on, what would you say were some of the biggest ecological concerns at the time that you came out with your PhD and do you feel like we've made any progress on those?

>> Jim Sprinkle: I think riparian is -- was one of the big ones then. And so we have -- you know, we have made some progress in some respects, particularly over the last two or three years with like virtual fencing. People are if they have some severe problems with use in riparian areas they've been able to help control livestock with the virtual fencing. And I know you've done some podcasts on that and I remember the guy that first started working on virtual fence, Dean Anderson down in New Mexico State, I mean he was - we thought he was way out there.

>> Tip Hudson: That was in the 1980s, wasn't it?

>> Jim Sprinkle: Yeah. I mean and seeing some of those pictures and some of the equipment some of those cattle were packing around it was amazing. And so he was -- he was some people would have thought of him "Well, you're just crazy." But look at where we've come. And so technology has helped us there. I think, you know, range monitoring is something very important. I think once somebody goes out and starts actually monitoring a range and looking at utilization then it really cues them in to moving cattle. So I remember hearing from a big rancher in Arizona, the [inaudible] Bar Ranch, and that's the one that had me come speak at the bull sale this spring. One of our -- my colleagues asked him, "Well, what's the most important characteristic for the people you hire?" And he said, "Well, frankly, it's just knowing when to move the cattle."

>> Tip Hudson: Wow.

>> Steve Steubner: And I might just add, Tip, you know, we've got a lot on life on the range about range monitoring and I would agree with Jim that it seems like a lot more ranchers these days are trying to pay more attention to what's going on with the range and certainly doing their own monitoring which now can be shared with the BLM and the forest service in the state of Idaho and department of lands. You know, it behooves you to do that for, you know, your future of using public range. And so I think, you know, that's been super helpful to see ranchers getting on top of that. And then to me also another big driver's been sage grouse in terms of sage grouse conservation. And I've seen -- done stories with ranchers, you know, that are fencing off important water spots for sage grouse, lekking grounds, or sharing their lekking grounds by elk. But I just think with the generations of ranchers that are managing now I just think we're -- we're just seeing them paying a lot more attention to what's going on on the range.

>> Jim Sprinkle: Yeah. So, Tip, just one more point here. In January of this year I was asked to come over to the three rivers conference over in Lewiston, and I was asked to present on matching cow nutrition with range management. And so I made a valiant attempt to do that and I had several comments after. Ranchers came to me. "I loved your presentation, but that's a lot of math." And so somehow we've got to make the math and the hands on easier to use. I mean it's fairly simple if you just you can look at the utilization and you can estimate how many more days you can be in a pasture. And that can be pretty valuable to you.

>> Tip Hudson: Yeah. It's interesting. I've collected quite a bit of monitoring data, both a lot of utilization monitoring, but also trend monitoring. And I have come to feel like the highest value in doing that isn't even the data that gets collected, but the time spent, you know, as Chuck [inaudible] said with your head on the ground and your butt in the air. You know, if you get out there and you're thinking about what's going on at the plant solar interface, what are animals eating, what are the patterns of what they're eating, how does that change by season or in response to heat loads, that observation has tremendous value. What are some ecological concerns today that you think are pressing that maybe we weren't thinking about 30/40 years ago?

>> Jim Sprinkle: Well, of course the cheatgrass fire continuation and, you know, there's -- some of our policies are impacting our range management. So it's pretty much standard if a piece of country gets burned and you're on a federal permit. You're not going to get to use it for two years. That's pretty much canonized. It's there's no -- the leaders, the national leaders of those organizations, have told us that there's no national policy on that. But people are afraid to take a chance. And so it's impacting in areas that have a high load of invasive annual grasses to begin with. We're just getting in a vicious cycle of well you burned. You let it rest for two years. Then it burns again. You let it rest for two more years. I mean there's people that have had certain pastures that they haven't been able to graze in 6/7 years. And we've got to end that. We've got to be a little more proactive and, as you said, looking at things on the ground and trying to manage our resource instead of just letting a policy dictate it.

>> Tip Hudson: Yeah. I would agree.

>> Jim Sprinkle: I might have put a target on my back for that one. But oh well.

>> Steve Steubner: I don't think so.

>> Tip Hudson: No. That's good. Are there any trends out there that are discouraging? And then I promise I've only got one more question.

>> Steve Steubner: Maybe, you know, trends either in the state of the science or in ranch management or in social public perceptions about ranching.

>> Jim Sprinkle: Yeah. I'll make a comment and I'm sure Steve will have one. So mine's not related so much to natural resources as it is to people. Critical thinking, you know, that is something so needed. And we're able to access so much information nowadays so quickly. And, you know, even the AI stuff can get you information quickly. But correctly processing and making valid judgments on that data is sometimes lacking. And, you know, I've always loved hearing you speak, Tip, and I think you're more of a philosopher and a scientist rolled up in to one, but some of the comments that you've made on how we use information in our lives I think we need to look at that and we need to encourage young people how to use information and how to apply it on the ground. There's a colleague of Steve and I's, a rancher over by Leadore, Merrill Beyeler, and his dream was that there'd be a natural resource boot camp down at Rock Creek where newly hired agency employees could learn about some of those skills and learn about how to talk to ranchers and learn about some of just how things work on the ground.

>> Tip Hudson: Steve, did you have any answer to that, trends that are encouraging or discouraging?

>> Steve Steubner: Well, I guess what comes top of mind for me in that vein is, you know, we've always tried to focus on the results and field work with ranchers and land management agencies in Idaho over the 15 years of doing life on the range. I think we've been really successful with that. And basically just, like I say, talk about things that are working well and share that information, try to educate people, and hopefully this will pick up on that. But I think, you know, another thing that goes on is just the politics of range management, you know, driven by who might be president of the U.S at the time. And so we've really just been, you know, just kind of been riding a roller coaster when it comes to, you know, trying to solve some of the important issues of ranch lands. You know, and it just kind of goes back and forth and I wish it could be more non partisan and just sticking with results that work.

>> Jim Sprinkle: Yeah. So what encourages and discourages you, Tip? I'd be interested in that.

>> Tip Hudson: Yeah. I think I'm encouraged at the number of young people that are going in to ranching. We -- you know, we hear that the statistics, national statistics, indicate that that's still aging, but I don't know. Somehow it feels like the statistics aren't necessarily catching what's going on at the local level because I'm -- 20 years go -- more than 20 years ago. 25 years ago when I moved to Ellensburg, you know, a local cattleman's banquet in a place that historically was a cow calf mecca in Washington state, you know, was nearly all people that were over 60. And the last few years that crowd is dramatically younger and much bigger. And I feel like I'm seeing that everywhere even though it doesn't seem like that's being captured in census data. So it does feel like young people are getting in to ranching and thinking about it in new ways.

>> Steve Steubner: Yeah. I think they're really creative, you know, and some examples of that and you know like we did a story with some ranchers over by American falls reservoir where those guys needed winter range and they're actually partnering with fish and game to address the aging vegetation around the edge of a wildlife refuge using solar hot wire fence. And mob grazing small areas at a time and doing a great job with it. Super, you know, staying on top of it. We did an art of range piece on that, Tip, and as I'm sure you recall, but anyway I just see -- I just see more of that. You know, where these guys know what to do and they're really thinking creatively about how they can achieve their objectives in different ways than before.

>> Tip Hudson: Yeah. I would definitely agree with that. The episode that we did on wetland grazing over there in southeast Idaho with Maria [inaudible] I probably had more comments on that than anything else we've done in the last few years. Like getting people's attention because it's one of these big problems that nobody has had any solutions for. We recognize that you can't just walk away from wetlands and do nothing and expect them to be habitat. But everyone's scared to death because of water quality issues to do any kind of grazing where there's surface water. And like you say the results speak for themselves.

>> Steve Steubner: Yeah.

>> Tip Hudson: I think those are encouraging. Last question, Jim. What's the next step in this -- in these research projects on the perfect range cow?

>> Jim Sprinkle: Well, we we're still crunching the data on this last study. And we're going to publish that and at least probably a couple papers. My PhD student hopefully will be finishing up this spring I hope. And then we've got the gene -- the DNA stuff that we still need to get run with Dr. Brenda Murdoch. She's the one that's been doing that for us from the University of Idaho. And so that will build our numbers of animals and we'll have more. We went after a big federal grant. We were with Montana State and we were going to have 600/700 animals that we were going to be following and looking at. And basically the premise was that we basically you'd be selecting animals based on hill climbing ability and trying to apply it in the real world. And actually see what happened. So we need scaled up what we've been doing, you know. My research we had 35 animals each year with the PhD student. And Derek's had a few more animals than that, but if we could show that yeah this works on the ground and we can have an impact on overall profitability I think that would be important.

>> Tip Hudson: Yeah. I agree. I meant to ask you toward the beginning there's quite a few names on some of these papers. Who has kind of been the core team in this work on the perfect range cow?

>> Jim Sprinkle: Scott Jenson. He's an area range extension person in the University of Idaho. He was formerly the agricultural agent in [inaudible] county. He's been very involved. Of course my graduate student Landon Sullivan. Dr. John Haul [assumed spelling] has been involved. Dr. Brenda Murdoch has been involved on the molecular genetics side of it. Dr. [inaudible] Brennan [assumed spelling] over at South Dakota State University is very skilled at handling big data sets and writing script to help you manage that big data set. And so he's been a go to person for that. Of course, you know, the people on the ranch [inaudible] accommodated the things that we've done and camera and west camp operations manager at Rick Creek. Dr. Benton Glaze has helped us with some of the stuff. And I'm sure I'm forgetting some people, but it takes a lot of people to manage this kind of research.

>> Tip Hudson: Yeah. Well, it's encouraging to see this kind of stuff still going on on a large scale landscape skill research, you know, trying to make it bigger and do stuff that works well for ranchers. For anybody who's not been to the page before you really do need to go look at the life on the range -- I think Steve the URL is idrange.org. But if you search for Idaho life on the range you can get there. And we will for sure put the link in the show notes on this episode. So watch the video. Read the article. And we'll link to whatever papers are open source also in the show notes. Jim, thank you for what you're doing. I look forward to seeing more of it.

>> Jim Sprinkle: Yeah. Thanks. I just one little thing is if there's any graduate students or scientists that are interested in doing this we do have some handbooks and resources available that we can share with people. I've had several grad students confer with me in the past.

>> Tip Hudson: Wonderful. Thank you. Steve, thanks again for joining us.

>> Steve Steubner: You bet. Thank you.

>> Jim Sprinkle: Thank you. Really enjoyed it.

>> Tip Hudson: Thank you for listening to the Art of Range Podcast. Links to websites or documents mentioned in each episode are available at artofrange.com and be sure to subscribe to the show through Apple podcasts, Podbean, Spotify, Stitcher, or your favorite podcasting app so that each new episode will automatically show up in your podcast feed. Just search for Art of Range. If you are not a social media addict don't start now. If you are, please like or otherwise follow the Art of Range on Facebook, Linked In, and X, formerly Twitter. We value listener feedback. If you have questions or comments for us to address in a future episode or just want to let me know you're listening send an email to show@artofrange,com. For more direct communication from me sign up for regular email from the podcast on the home page at artofrange.com. This podcast is produced by Connor's Communications in the college of agricultural, human, and natural resource sciences at Washington State University. The project is supported by the University of Arizona and funded by sponsors. If you're interested in being a sponsor send an email to show@artofrange.com.

>> Speaker 1: The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed by guests of this podcast are their own and does not imply Washington State University's endorsement.

Life on the Range article and video, The Perfect Range Cow? University of Idaho research study identifies the gene marker for hill-climbing cattle

Research article at Translational Animal Science, "Identifying genetic variants affecting cattle grazing behavior experiencing mild heat load"