Jim O'Rourke and Barbara Hutchinson have been part of the effort to have a United Nations International Year acknowledging the importance of rangelands and the people of rangelands for many years. On March 15, 2022, the UN General Assembly finally approved this proposal. Listen to Jim and Barbara describe why this matters for people who already know and care about rangelands and how you can heighten awareness of the social and ecological importance of rangelands worldwide.

Transcript

[ Music ]

>> Welcome to The Art of Range, a podcast focused on rangelands and the people who manage them. I'm your host, Tip Hudson, range and livestock specialist with Washington State University Extension. The goal of this podcast is education and conservation through conversation. Find us online at artofrange.com.

[ Music ]

My guest today on The Art of Range are Barb Hutchinson and Jim O'Rourke. Barb is a natural resources librarian at University of Arizona, and she has been working at retiring. Jim has been a range management professor at Chadron State College for a few decades. And again, I think I heard that Jim retired too some time ago, but appearances deceive. Retirement is a funny word. Jim and Barb, welcome.

>> Thank you. We're glad to be here.

>> Thank you, Tip. Yes, we are.

>> You both have been doing this for some time, and I think it's, let's talk a bit about how you got into doing rangelands work as opposed to all the other things a person could do with their lives. This is still not a real big social niche in the global scheme of things. We all happen to think it's important, but it is a little bit unique. How did the two of you end up doing work related to rangelands?

>> Mine is probably the most unusual story. I started out as a librarian with a master's in library science and eventually a PhD in higher education, which may seem like an unlikely fit for range science and education. But I managed a special library for many years. The Arid Lands Information Center at the Office of Arid Land Studies at the University of Arizona. And this led to many interesting interdisciplinary projects, including the development of the rangelands' partnership, which Tip talked about before, but this is nearly a 20 year collaboration among Western and Great Plains land grand universities. The mission of the partnership is to bring quality information and resources about sustainable rangelands management to stakeholders, a variety of stakeholders, through the creative use of technologies. And most specifically, a website and database which now is called the Rangelands Gateway. And I think some of these links are in the notes for this podcast. So the partnership is all about collaboration and outreach, and it was through, it was actually at a time I was sitting at my desk and watching in 2015 videos coming out from the Natural Resource Conservation Service, NRCS, that were related to the International Year of soils. And they were wonderful little, small, short clips that really taught me a lot about soils and have a greater understanding. And I thought boy, this is what we need. We need an International Year of rangelands. And that sort of was the beginning of this latest round of working towards that end.

>> Yeah, I think I've got one more question on that. I was pretty sure this was the first time we've had a sure enough librarian on the podcast. Describe a little bit of what a natural resources librarian does.

>> Well, traditionally, in a university science library, and we have science library and natural resource librarians that are part of the partnership. That's part of the joy of it is that it is an interdisciplinary kind of effort linking librarians, information science, information technologists and rangeland specialists together to bring information to the public. And so a traditional science librarian would be working with students and faculty on the campus, working to answer questions about natural resource information resources. But in a special library like I worked, we actually gained funding for various projects, and it was through a project with the National Agricultural Library back in 1995 that we first got started on developing a website about rangelands management. And it wasn't very long before we realized that doing that for Arizona was not really effective or efficient because in the issues that we were talking about like invasive species and so forth don't stop at political boundaries. And so that's how the partnership grew to this 19 land grand university collaboration.

>> Yeah, I'm a committed bibliophile, so I'm prone to like librarians. In my experience with the rangeland partnership, which as you mentioned is a collaboration of range extension specialists and librarians has only served to confirm that fondness. Jim, what, what has been your pathway towards being a range guy?

>> Well, my introduction to rangeland, rangeland was in the late 1800s. It's a little bit older than I am, but my family homesteaded north Gordon, Nebraska in the late 1800s. And my grandad was a cowboy on the famous Spade Ranch in the Nebraska Sandhills, one of the open range big ranches for decades. And I could go on forever about the legal battles between Bartlett Richards who owned a ranch and Teddy Roosevelt and the Range Cutting Act and Fence Cutting Act and all that stuff. But anyway, my grandad was a cowboy, really involved with grazing livestock on rangelands. That, I think, stimulated my father to get into the field of range management, and he's a graduate of Colorado State University and range in the 1940s when I was born. And so he worked for US Forest Service for his career in Colorado and Wyoming. And so my, all of my education was in range from day one. So I learned how to run trans X [phonetic] and do all that kind of stuff and mark timber and count sheep and cattle with my dad working for the Forest Service before I was even in high school. I went on then with a bachelor's degree at Colorado State University in forest range management. Worked for the Forest Service in Arizona. Then went back for a master's degree at the University of Arizona. Got drafted, by the time I came back, started a PhD at the University of Wyoming. Worked, went to Columbia for a short period of time, looking at ranches for a rancher over in Gillette, Wyoming. Came back, milked cows for the winter, not many range jobs in the middle of winter in Wyoming. Then I went back to the University of Arizona, finished a PhD. And then I spent quite a long time in Africa. I spent eight years total, 2 1/2 years in Tanzania on the Maasai Range Livestock Project as a range specialist and essentially an extension effort working with Maasai Range officers, working with grazing practices with the Maasai Tribe. Then to Morocco where we were helping establish range, or different departments in their Institute of Agronomy in Veterinarian Medicine. And so my job was to set up the range program there. Which we did. Came back from that, and I joined the range faculty at Utah State University. I was there for seven years. Then we went to Nigeria for two years where I was training officer for the, for a World Bank livestock project in Kaduna. Came from there then to Chadron State College in 1988. And so I've been here ever since. We moved to the family ranch which is south of Chadron, Nebraska, so we run the ranch as well. Right after getting to Chadron, it was obvious to me that we're in the heart of rangeland. We're right in the transition between Tallgrass Prairie to the east of us and the Nebraska Sandhills and then Hardground to the west. So I started a range management program at Chadron State College, which is now, if not the largest in student numbers, one of the two or three largest programs. Mainly because we cater to students who are going back to a farm or ranch. It's not a program that's trying to educate graduate students going on to faculty positions. A lot of our graduates do work for government agencies for the NRCS or the Forest Service, BLM. But I retired in 2002 mainly because I was at that time, well I've been active in the Society for Range Management for a long time. I'm a 60-year member this year. I was on the board of directors, then I was elected as, there was a presidential change, so I served as interim president in 2002. At that, during that same period of time, I was elected to the continuing committee, which is essentially the board of directors of the International Rangeland Congresses. So I began that in Salt Lake City in 1995. Served on that continuing committee up until 2003, which was a Townsville meeting in Australia in '99. Then the 2003 meeting in South Africa, Durban, South Africa. At that point, I was supposed to go off the continuing committee, but nobody was willing to sit for president, so they asked me to serve as president, which I did then for the meeting in Hohhot, Inner Mongolia, China in 2008. When that Congress was over then, I then started helping the other countries that were preparing for International Rangeland Congresses. And the person who was our secretariat at that time of the International Rangeland Congress, Gordon King from Australia, died about three weeks after our next Congress in Argentina. He had been serving as our secretariat, which is a person who really keeps the website up and mailing addresses up and helps next countries help plan their Congresses. So I then stepped into that position. I'd been serving as the secretariat through the Argentina Congress in 2011. The Saskatoon, Canada Congress in 2016 and then our most recent just last year in 2021 in Nairobi, Kenya. And I still serve in that secretariat position. But with regard to the International Year, Barbara had mentioned that she had started some discussions in the outreach committee within SRM in 2015. And so she organized a meeting at the Corpus Cristy meeting in 2016 of the outreach committee and the international affairs committee. And it was at that meeting that we really put our heads together on who we ought to start involving in getting this thing rolling for an International Year. And it was after then that we started putting a long list of people together, a support group, I think it was a steering committee, we call it a first. That's when Maryam Niamir-Fuller was added and Ann Waters-Bayer. And those two ladies along with Barbara are the ones who have really carried this thing forward.

>> Yeah, let me interrupt you there. I don't think we even announced yet that we're talking about the International Year.

>> Okay.

>> But that's where we're at definitely in the interview. And I hate to announce this. I was just going to read directly from the press release.

>> Okay.

>> On the 15th of March 2022, the United Nations General Assembly in New York unanimously declared 2026 the International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists. This final approval is the culmination of the International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralist movement that grew over several years to become a global coalition of over 300 pastoralists and supporting organizations, including International Livestock Research Institute, the ILRI, and several United Nations agencies. And building on these efforts, the government of Mongolia and 68 cosponsoring countries developed and put forward the resolution to the United Nations General Assembly. So that's the announcement. Probably most people that are in the world of range knew something about this at least that it was going to be coming. But it really is pretty significant to have this declared as an International Year. So we can jump into it, what is the International Year for those that maybe have, you know, only heard of these things but never really thought about it. And what was the process for that designation? You began to get into the history of that, and I think that's definitely worth talking about.

>> At the International Rangeland Congress in Inner Mongolian Hohhot, Inner Mongolia China in 2008, we passed a resolution that we would like to have the UN designate an International Year. And one of the members of the committee at that time was a lady who worked for FAO in Rome, Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations in Rome. And she took it back to Rome and tried to work on it, but it didn't go anywhere because we weren't following the correct process we learned. But it took us a long time to learn that process. And so we passed a similar resolution at, in Argentina in Rosario. But the same thing, it was a resolution. There was no action taken. And then it was in Corpus Christi when Barbara and I and several folks got together and started organizing this steering committee for an International Year where things started to happen. And so that summer, in 2016 at the International Rangeland Congress in Saskatoon, we passed another resolution. But we held a meeting at that point, both virtually and in person, to engage people in starting to put their heads together and how we do that. And that's when Maryam Niamir-Fuller who had previously worked in the UN system, and Ann Waters-Bayer were added to the system. So Barbara, go ahead.

>> Yeah, that's a wonderful introduction. As you can see, it's taken us a long time to get to the point of actually having a designated International Year. International Years are wonderful ways of calling attention to particular issues and possibilities for gaining increased knowledge, I think, that will help improve policies and that whole interaction of social, economic, environmental and political issues. And so I think what happened, the main thing I think Maryam brought to the table was that she had connections at the UN Environment Program, UNEP. And it was actually at several UNEAM, the UN Environment Assembly Meetings that we actually gained some momentum internationally for putting together really a consortium of people that would work towards this end. And it took us a long time to figure out the process. We thought originally that we could go straight to the UN general assembly and submit this proposal for consideration, and it would be discussed and voted on. And we could turn this around in a year. Well, that didn't happen at all, and it took us a long time to understand that we needed to, there was a process that we needed to go through, and that involved having a country come forward to spearhead a proposal for an International Year. And we, of course, we were originally talking about rangelands. But then we found out at the same time that there was a whole group of pastoralists NGOs that were working towards, that also wanted an International Year. And so it took us quite a while to have this discussion amongst these two worlds to come together as one. And once we passed that hurdle, then we could focus on identifying a country to take this forward. And luckily, I think it was a UNAI four that the Mongolian government came forward and said that they would sponsor this proposal. Jim, you had more to add?

>> Well a good point that you made on countries taking it forward, very early on we, when we started the planning for the International Rangeland in Nairobi, the Kenyans were very interested in leading this and so they immediately had a resolution passed and signed by the minister of agriculture and by their ministry of foreign affairs, and they sent that resolution directly to the United Nations. So we thought boy, we've done this correctly. We've got a country behind it, and it's gone to the UN General Assembly. Well, what we learned later on was it had to first go to a committee of agriculture, what's called COAG, C-O-A-G, that is membered countries of FAO was then agree on this resolution. And then they take it to FAO, and then FAO takes it to United Nation General Assembly. Finally then, as Barbara mentioned, the government of Mongolia then took the resolution to COAG, and then it went to FAO and the UN General Assembly. So it took us a long time to figure out this process, as Barbara said. Even though we thought we understand the UN system. We didn't really understand the process.

>> Yeah, we should also say that all during this time, we are the steering committee that became the support group for the Mongolian proposal, which involves people from all over the world in really almost every country. And we really had to garner letters of support. At one time, we were supposed to, in order to get ready for COAG, besides having letters of support for the proposal from organizations and individuals, we needed to also have side events. So a side event is a way to invite people to come and hear presentations and videos and make your pitch for what it is you're trying to do. And it was, in order to get ready for the, normally, those meetings would have been in person. For instance, the FAO, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Committee on Agriculture normally met in person. But because of COVID, we had to, and we didn't hear about this until about two weeks before the meeting that we needed to prepare a virtual side event. So at that time, we started, while we had a very preliminary website that was just sort of a place where we kept resources and background documents, we now took the web and turned it into what we called an online booth, and we collected videos from all over the world telling stories about pastoralists, telling their own stories. And in showcasing the rangelands of the world and how these are all interconnected. And we haven't even talked about some of the data which is that more than half, now they're thinking 54% of the land surface is considered rangelands or grasslands or savannahs. There's all kinds of words that we use. Maybe Jim will want to talk about some of these definitions. And yeah, so, so it's just been a long process but a very positive one in bringing all these worlds together.

>> Am I right that we just came out of a UN decade on soil health and that we're now in a UN decade of ecosystem restoration?

>> Yes. In fact, not only that, but a decade of family farming. And we have worked, we are working with all of those initiatives as well. Jim, you have more to add there?

>> No, I think you're right. Yeah, yeah, you're right on, Barbara, yep.

>> Well I think this is exciting probably because I regularly find myself giving the elevator speech to people who think that range is the thing that you cook your breakfast eggs on. And I think the other thing that's maybe useful to talk about is we get into some of the messaging, some of the things that we're hoping to accomplish with this International Year are misconceptions about rangelands. And in fact, even rangelands textbooks 50 years ago described rangelands by what they weren't. You know, it was everything that was left over after you excluded croplands, cities, open water, forest, you know, something that has a different more specific use. But you know, more recently we have described rangelands by, by what they are, namely a land type or a vegetation type. And I think this could be one of the, one of the major benefits of an IYRP. But maybe I think I first want to ask, and I'm probably not the first person who's wondering this. What is a pastoralist?

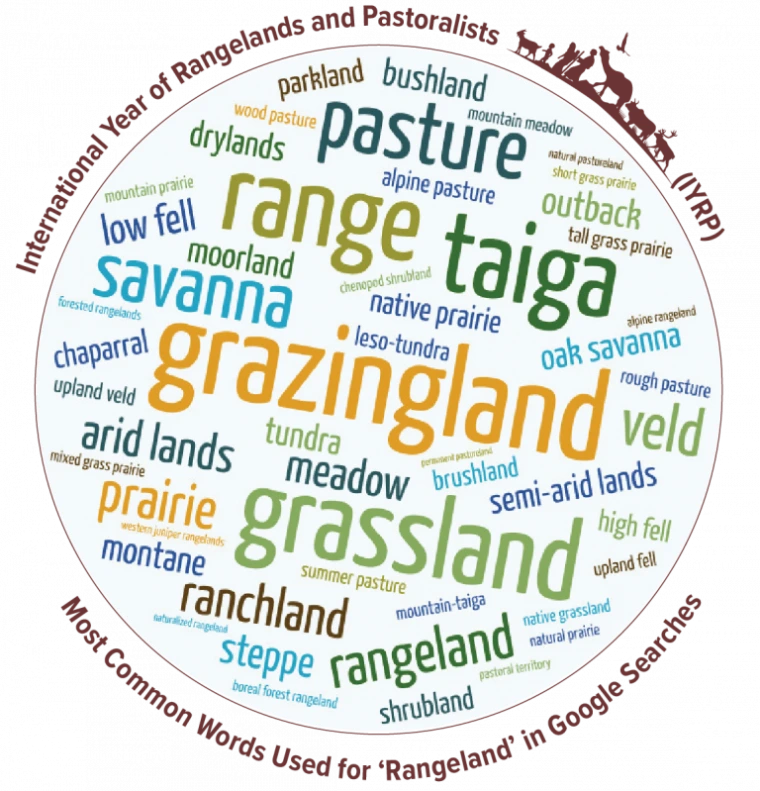

>> Good question, Tip. One of the, one of the documents that the steering committee support group developed a couple of years ago was what we call word clouds because the designation, of course, is for rangelands and pastoralists. Rangelands, a bit more understood around the world, but pastoralists is really not well understood, particularly in the United States. So this word cloud on pastoralists is a circle that has every name for any person that is involved with the using of rangelands throughout the world. And so to me, that word cloud is extremely important to have posted in extension offices and banks and in rotary meetings and every place in the US to explain to ranchers in the United States that they are one. They are a pastoralist, a rancher, a cowboy, a cowgirl or whatever. And so that's, that has to be one of the first efforts is to bring everybody into the discussion once they realize that they a part of this and they've got stories to tell. And some very important things that they've done to really make the world a better place. Rangelands is a term that's less well known, I guess, around the world. Or not as, not as less well known as pastoralists. But all sorts of terms for what we call rangelands, whether it be savannahs or whatever, all way around the world. So we have another word cloud for that. But yeah, definitions is important. Sometimes we get a little bit too hung up on definitions. But the main thing is that we understand that we're all a part of this. Anybody that uses rangelands in any way, whether it be for hunting, for recreation, for aesthetics or for livestock grazing, they all need to be a part of this. And I think, I think it's good that we, if we have an introduction here to what are rangelands? How important are they?

>> Yeah, and regarding pastoralists, just a couple more thoughts there, I think I have an association, I guess the connotation that I have of that word is that it's a way of living that's somewhat broader than an economic enterprise. But I'm not so sure that that's very foreign to the way most ranchers operate in the Western US, even though we probably have different connotations for the word rancher versus pastoralists. You know, but survey data indicate that many ranchers, if not most ranchers, are doing it because they love it and they think it's important. Not so much because they're getting 10% rate of return of investment on it. And so I think there's quite a bit of similarity between, you know, what we might think of as pastoralism in another part of the world where you have a lifestyle that revolves around animal husbandry, raising livestock and moving with livestock, whether or not being a nomad is part of that. I'm not so sure that it's very much different than the way a lot of family ranches function in the West, in terms of being a lifestyle and not just a way of making some money.

>> You know, Tip, you're right on, absolutely. I mean one good example of that is the concentration a lot of folks have in Africa on mobility. And that mobility is often talking about movement between countries or long distance moves. But US ranchers are involved in transhumance, and they're involved in mobility as well. Whether it's a short duration grazing system on a local ranch or whether it's grazing in the summertime on rangelands and the wintertime on corn stalks. Or whether it's summertime on the mountains in Utah and the wintertime on salt desert shrub in the wintertime. So mobility is used around the world but in a different sense somewhat. But they're both sorts of operators are engaged in their livelihood from rangelands.

>> Yeah, and I think that we need to think of pastoralists as stewards of the land and who've been caretakers for a millennia over rangelands and grasslands around the world. There was a, I don't know if it would be helpful, but in the gap analysis which was done under UNAP [phonetic] by a number of the people that are involved in the steering committee or the support group, have a definition of pastoralists who are people who raise or care for wild or semi-domesticated animals or domesticated livestock on rangelands and include ranchers, nomads, graziers, shepherds and transhumant herders. And I think the word clouds that Jim discussed are, were a result of looking at pastoralist terminology on Google and doing searches and coming up with all of the words that are used around he world for pastoralists. And then I think it's easier when you see that word cloud that you can identify with one of those groups. And the same with a definition for rangelands because these are complex landscapes of grasslands or semi-desert grasslands, shrublands, woodlands, mountain meadows and so forth. And I think it's important to realize that there are multiple ways of talking about these lands but that they all, they have a significance for all of us.

>> Yeah, and I like the, I like your term land steward. I think maybe outside of our own social, social group, people see ranching and even pastoralism as a kind of extractive natural resource industry, even if it's gentler than, you know, something else. But you combine this idea of stewardship with the complexity of semi-arid landscapes. And you realize that this is not simplistic work.

>> Not at all, and in fact, it has direct relationship to clean air, clean water, the sequestration of carbon in the soils has been little understood and on rangelands. The focus has been, and really rangelands have been undervalued as the solution to climate change. And actually, I think there's new research that shows that there is more carbon stored in soils and rangelands than in forests. And so these are some of the misconceptions that we want to inform through new research and through new education that what the International Year will provide us a new forum.

>> You're right on, Barbara. I've, we've talked about the fact that 50% or greater of the land surface of the world is made up of rangelands. You know, think about driving from Mexico City to Edmonton, Alberta. You're in rangelands. Talk about driving from North Platinum, Nebraska to San Francisco, you're in rangelands. This is drive through country for a lot of people or close your eyes, take a nap kind of country. But they have no idea that that kind of country is, makes up 50% of the land surface of the world. Now how important is that? Barbara just talked about carbon sequestration. So let's talk about what that means. When a plant grows, it takes in carbon dioxide from the air and gives off oxygen. So the carbon from that carbon dioxide that's taken in by the plant is stored in stems and leaves and also in the root systems. When that plant goes dormant, the stems and the leaves die, fall onto the ground as litter. That litter then is converted into organic matter that builds soils, and that carbon is stored in the soil. But underground, the thing that we don't really realize a lot of times is that that root system is at least as large, if not larger, than the above ground part of the plant that we see. And 1/3 of the root system in a grass plant is, turns over annually. So in every three years, the entire root system of that plant dies. It is added as organic matter. And then that carbon that's contained is stored in the soil. So if 50% of the land surface is rangelands and that sort of carbon sequestration is taking place, it's an extremely important, if not the largest storage ecosystem in the world for carbon. Then when we bring in the concept of grazing versus not grazed, you know, let's go back and look at bison numbers. People want to criticize livestock sometimes, domestic livestock, there were 30 to 60 million bison in the, just in the Great Plains in North America. There are only 30 million domestic livestock in the entire US today. So we are, we are far less stocked in grazing animals in the Great Plains than there were with the bison. When that, when a plant, and so therefore, those plants evolved under grazing. In order for those ecosystems to be maintained in the system that we wanted to see during bison days, those plants have got to be grazed in order for those plants to stay in the system. When a plant goes ungrazed, it stores carbon but only until that plant goes dormant. A grazed plant, on the other hand, is, of course, storing carbon as it's conducting photosynthesis. The part that is grazed off, of course, is passed through the animal and added as carbon in the manure to the soil and builds soils. But the plant that has been grazed and in its regrowth is conducting more carbon sequestration. So there's four more carbon sequestration occurring in a grazed plant than in a nongrazed plant. And so the importance of good grazing management is really needs to be understood by the general public that as an example, I do a lot of rangeland health work. And I've done rangeland health work on over 100 ranches in Nebraska. And 95% of those folks are just doing a fantastic job. The range condition, the carbon building, the soil building, the healing of blowouts, all of those things have improved dramatically over the time that my grandad was a cowboy in the Sandhills of the, in Central Nebraska. You know, that's, the Sandhills in Nebraska are the largest reclaimed sand dune in the world. And so it, and it's all because of good grazing management. So rangelands are extremely important to the general public to realize that rangelands are storing the carbon that they are emitting from cars and buses and trains and industrial activity.

>> Jim, do you think that there is a possibility or the opportunity in all of this to, to have a little bit different flavor in the language that comes out of some of the organizations associated with the United Nations regarding livestock, because it seems like most of what people hear, and this may be why, you know, when, you know, Joe Rancher in rural Nebraska hears that the United Nations has declared an IYRP, they may have a somewhat cynical response. Because most of what they hear out of the UN is that livestock are destroying the earth, not helping to maintain a healthy carbon balance. Is there a chance to influence some of that do you think?

>> Yes, I think so. And in fact, ILRI, the International Livestock Research Institute, that's headquartered in Nairobi has really taken this on, and they're a part of that overall UN system. And they are counteracting that view. So I don't think that the UN really is opposed to domestic livestock. I think through the Food and Agricultural Organization, I think they're behind animal agriculture. I think, to me, the message needs to be really local, and every country, we've developed 10, 11, is it, Barbara, regional support groups around the world. And each one of those groups will then develop messages. And I think Barb will talk about that in a little bit here. But when we look at that messaging which you're talking about here, I think it really comes down to not just a country but a state within a country and a county within a state. I think its message is to the Chamber of Commerce in Chadron, Nebraska, the Elks Club, the, all of the, all of the organizations that meet to bring those messages to those urban audiences. The livestock community, the ranching community, understands that carbon sequestration thing and the fact that methane production is far less on rangelands than all of the emissions that occur from other uses around the world. So, you know, when we, when we talk about urban audiences, we're not talking just about downtown New York City or downtown LA, we're talking about downtown Crawford, Nebraska, Chadron, Nebraska, KC Wyoming. I mean there, there are a lot of folks that are not aware of these facts.

>> Yeah, and I feel like one of the things that's unique in rangelands-based livestock production as well is that it's, there's this tie between ecological sustainability and economic sustainability that's unique. You know, on cropland, you can pay for enough inputs to make a crop happen. But on grazed rangeland, ranchland, if you run it into the ground ecologically, you pass a certain point of degradation where it's no longer possible to make a living there. And I think that's intuitively understood by most ranchers. You know, part of that is we've been doing this long enough now that if somebody is not protecting the productive capacity of their land, they're probably not in business anymore. And I feel like we, at least I hear way more stories like what you described, you know, where a rancher says you should have seen what this looked like 50 years ago. And they always mean that it looked worse then and that it looks better now. And I don't think that story gets told very effectively either.

>> Absolutely. In fact, we're, we have a program going on right now at Chadron State College that Pat Shaver, who's one of the coauthors of the Rangeland Health Book, has been giving a weekly program for ranchers and students. And the ranchers are filling the room wanting to learn. A lot of them have conducted rangeland health already on their place. And they're wanting to learn more things about how to protect things better. They know that, they know the difference between a degraded system and one that it is in good health. And they're using ecological slide descriptions and state transition models to say I'm trying to get this back to where it should be. And in a lot of cases, I'll have to say that that degradation didn't occur by domestic livestock. It occurred by bison.

>> Tip, I wanted to give kind of a success story that's already happened because you talked about the decade for ecological restoration. And it turns out that some of the language was anti-grazing in some of their literature. And in fact, so some of our people that are involved in that decade as well as the International Year contacted them and worked with them on changing that language. And so now that is not in the description of the decade. So we're reaching out in a variety of different ways to try to chance some of these misconceptions. And we have the focus now is on what are we going to do? What kind of educational programming, what kind of outreach can we do that will meet the information needs and interests of a variety of audiences. So that we don't just talk to ourselves in the academic community or even among ranchers. But we really reach out to, as Jim said, the urban people who are living in urban settings and having not so much attachment maybe to rangelands. And so now our focus is, and our discussions are going on of where we're going to put our energies and time in the coming years leading up to and during the International Year.

>> Yeah, that was something that I had not thought about before, just observing from the outside these International Years. I realize now that they're, you know, a decade of work leading up to an International Year. You know, we're sitting here in spring of 2022 talking about something that is almost four years away. What are your thoughts about how we build up to that, you know, maintain some momentum without people forgetting about it? You know, then what's left to do during the International Year? Do you guys have any thoughts on what, I suppose on the one hand you could say that we've got a five-year run where because of the International Year designation we have the chance to talk about it kind of on the international stage for longer than just that one year.

>> Absolutely. And in fact, we're already planning for each year and then for the 12 months of the International Year. We've already got plans in place for 12 themes for during the International Year. We had a meeting yesterday with the North American Support Group for the IYRP. And we already are talking about things we can do right now short term, and one of those is something you, Tip, brought to our attention, which is that extension professionals are getting called by media to talk about the International Year and what it means to local communities. And so we're working on putting together a little media packet to go out to extension right away. And working with compiling sort of messaging and slogans, and of course, we're really focused on social media. And we hope everyone will go to our social media outlets, Facebook, Twitter and Instagram and like us and share us. It's something everyone can do to help us. And then we're, of course, looking ahead to potentially hosting a film festival of short films that we'll collect from around the, especially North America. And there's all kinds of, we're working on podcasts, such as this one. And also, we're even exploring the idea of a full featured documentary on the rangelands of North America. And so you're going to be hearing more about these, I think, in future podcasts, Tip.

>> You know, another good point that Barbara makes, when these years get designated by the United Nations, then a UN family member is given responsibility to lead that. Well in this case, FAO has been given a charge for the lead. But they have so many International Years that they're dealing with that we've learned that they probably are not going to really take much activity or much action on this until 2025. And so just a year before and then the year itself. And so we want to, and it's looking to us like it's really going to fall back or stay with the international support group or international steering committee to keep this momentum going. And so what we've really tried to do is develop and have developed these 10 or 11 regional groups, regional international support groups around the world. So that each one of those regions then starts to develop their own plans but also then to give that charge to individual countries within those regions. Because there's going to be different messages within each country within each region. And so the emphasis for the next several years is going to be really gearing up those regional groups and those country groups to do their own planning for what is, what are the significant messages that they need to deliver. Barbara mentioned the 12 monthly themes, and out of necessity, of course, there was a title put to a certain month. But in a lot of cases, for instance women on rangelands, in India they have a particular month that they already recognize women in agriculture. And that happens to be a different month than the month that we had in our 12 monthly themes. So it's really going to be a matter of each country taking those 12 monthly themes and then putting them in the month that makes sense for their individual country. But so there's just a tremendous amount of effort that's going to have to take place over the next at least three years before FAO kicks in of volunteer activity from range folks and pastoral peoples around the world. So we're needing a lot of help.

>> Yeah, I could, I could say, Tip, a little bit about the 12 themes. Maybe that would be of interest. Because I think, and as Jim pointed out, they will be adjusted according to the region's needs and interests. But at least it gives a framework for starting out for just about how we did today, which is talking about in January looking at the importance of rangelands, grasslands and pastoralists and sort of making those definitions to get everybody on the same page.

>> Yeah, I would love to hear about that. I have not seen the 12 themes yet.

>> Okay.

>> And I think one of the points of this, you know, as you know, the listenership for this podcast is mostly range people, ranchers and range professionals of various kinds. But I think one of our goals here is to help, help those of us who should be the ones doing the preaching to know what that message is. You know, what of the things that we need to communicate to the non-range world about what's going on? And I would love to hear about the 12 themes.

>> Yeah, before Barbara says that, Tip, I think you've got to, made a very good point. We have to stop talking to ourselves. These podcasts are tremendous for us to understand the importance and anyone that picks up the podcast needs to go to the rotary club, to the chamber of commerce meeting, to the bank, to the shoe store, stop, don't stop talking to the livestock organizations. But livestock organizations, go to the rotary club.

>> Well said.

>> Yeah.

>> Barb, it's all yours.

>> I'm thinking, you know, it's not only, it's the who and the what and the how that all has to come together here, I think. And that's what we're starting to tackle. The themes though, are sort of these overriding issues that we really want to bring to the fore and have more discussions with people from different stakeholder groups so that we can have a conversation about these things and develop our own common knowledge, I think. So if we start out with kind of laying the groundwork of the importance of rangelands, one of the big issues that Jim's already alluded to is land tenure, the whole issue of mobility of being able to move your livestock around. Which actually helps increase the health of the range. Then we go on to kind of the whole ecosystem services which have been traditionally undervalued for rangelands. And really, having a better sense of what those ecosystem services are how much they affect all of us. Then we have, we certainly want to have a very strong focus on climate change, on the ability to work with variable climates. And this is something that rangeland stewards, ranchers, have considerable knowledge of and can help guide this, I think. We have the whole idea of biodiversity, ecosystem services, as I mentioned. Then we have the linkages to soils and clean water. Also, and of course, the whole idea of livestock products and some of the new, I think, what do you call it, boutique kinds of resources, natural resources. Now, I mean, a lot of us are going to our farmer's market every Sunday and buying our local beef and our organic vegetables and so forth. I think all of these things are part of this process of becoming more tied for all of us, even those that wants to live in an urban environment to be more tied to the land. Jim's already mentioned pastoralist women. We also have a month we'd like to focus on youth and bringing youth into this program. And getting them out, I think, to see and to participate and be a part of the rangelands resources and the rural culture. And then I think the final one was sustainable technologies and innovations. And these are the things that will help us do even more soil improvement and might be involved in renewable energy production and so forth. So we have a very ambitious outreach program that we'd like to see happen. And as Jim pointed out, we have 11 regional groups working on this in their own regions. And the North American group is quite active and lively. And we're looking forward to working with everyone on bringing these issues to the fore.

>> You know, one of the 12 monthly themes that I think might be the most difficult is the science behind good range management. I think all of us, ranchers, urban folks, need to spend more time really learning the science behind good grazing management, carbon sequestration. What happens in using the four principles of range management, proper numbers of livestock. Proper season of use. Proper kind and class livestock and distribution. What does season of use do to changing the plant community to the plant community that you want to see for better production from a livestock standpoint but also from ecosystem services, hunting, recreational opportunities. Which a lot of ranchers are already involved in. So ranchers know ecosystem services. They're taking advantage of that. But everyone needs to understand that there is science behind this stuff.

>> Yeah, that's really important, and I think we didn't really speak to that until now. And really, one of the things we want to do, and that build off that gap analysis that was produced through UNAP with members of our group is to really fill those knowledge gaps and have the science, have good science behind all of this. And there's been, I think, a lack of value and funding for this kind of research that we hope this International Year will fill that gap as well.

>> Yeah, I was just thinking that the last century has been, there's been, yeah, the kind and the number of changes that have occurred is pretty breathtaking. I was initially thinking that it would be interesting to compare some kind of a rangeland health assessment, you know, for this country, if not others, looking from 1926 to 2026. And I'm not sure what resources they might be to do that from 1926, but there were people looking at things back then. I was actually just interviewing a couple of days ago a man who was born in 1923 in Eastern Montana. You know, grew up with nine kids in a shack that's half the size of my office room. And was describing the vegetation of that part of Eastern Montana. And you could see from an ecological site description, that what he was describing was really the third stage down in degradation sequence and was not representative of what had been there. And I think many places have kind of come back to, you know, if not a reference state at least to a more functional state than what they were in, you know, going into the dust bowl era where there was prolonged drought in much of the Great Plains. But I think there have been a ton of changes from primarily from improved scientific grazing management on rangelands all across this country anyway. And much of what we saw at that time was even the result of, you know, bad financial management not just inadequate ideas about range management. But that comparison, I think, would be useful. And it highlights the importance of having a good understanding of plant communities and how to manage them.

>> Absolutely, Tip. You know, Dick Hart wrote a great article in Rangeland several years ago about what the country looked like when European settlers arrived, when Lewis and Clark came along and what impact bison were and what terrible range condition things were in because of that bison use. But there's a lot of photographic studies. Kendall Johnson did a great one for Utah long-term photo points taken over 50 years difference or 80 years difference. There's been a great one in the Black Hills. There's a lot of those photographic studies that show us what things looked like years ago and looking at relic areas what they could look like. And that's what ecological site descriptions have been based on is what did it look like way back when it was hammered and what could it look like. And that's where we're moving with state and transition models and the different plant communities that you just talked about in reference states and how many states, how many plant communities down line are you from where you could be. And that's the science that I think we all need to get involved with and understand that we have the science there. And we know how to move these plant communities into stable systems. 4 And we just need to understand that science, all of us.

>> You've alluded to it a little bit. Go ahead, Barb.

>> I was just going to say, I just want to say that yes, we need that good science, but we need it translated into good policy. And I think that's, you know, the ultimate goal has to be overall, you know, if we change people's perceptions broadly then that will translate into better policies that reflect, you know, excellence in knowledge and values, people, values, the land and yeah. So, that's our ultimate hope here, I think.

>> I think that is a significant point that policy is important. You know, we live in what is still a remarkably free country. I mean we have environmental regulations that set some limits on things that can be done. But for the most part, you know, landowners have a pretty free rein with what they are able to do or not do with their own land. And that's not the case everywhere else in the world. Rangeland sociologists have pointed out that rangelands and the people of rangelands are often marginalized, meaning they're left or pushed to the margins of mainstream polite society, and especially positions of power. I think it's interesting that we even see some of that in sensing seemingly some mundane as a map, you know, where you look at a continental or world map that often have, you know, what are considered these primary land uses or the higher value land uses like forest and cropland are an array of bright interesting colors. And then you have rangelands in varying shades or gray or crosshatch in the middle of this color. And, you know, the legend says barren land or uncultivated land. You know, it's what it's not rather than what it is. And you know, our language in our symbology, I think, betray some of these prejudices, at least internationally. And it is important to draw attention to people groups in other parts of the world that don't have, we assume, I think what made me think of that is when we talk about science, we assume that we have the freedom to make decisions and take action based on what we see as applicable science. And not everywhere do people have that kind of agency, even if they had the information.

>> Yeah, I think that's quite true. And that's why we, we have a, we have this global view, but we also want to take it down to the local level. And so we have high hopes that we will address many misconceptions and lack of understanding about pastoralism and rangelands through this International Year.

>> One of the main messages to the general public will be to stay awake from North Plat to San Francisco and stay awake from Mexico City to Edmonton. Because those lands are storing your carbon that you're emitting.

>> Yeah, get back on Route 66 and drive it without cruise control?

>> You know, another thing that's really quite a success story that I don't think very many people know about is what the work groups like Bird Life have done in migratory bird habitats from the Great, all through the Central Great Plains from Canada down through Mexico working between environmentalists and ranchers and agency officials and so forth. And because the, as most of us have heard, that there are lots of bird populations are dying out because of lack of habitat. And because maybe those lands have been turned into, or have been developed or have been turned into cropland or something that doesn't serve the wildlife population and migratory birds. And so, we need these kind of collaborations, and we see these successes in small ways. We need to expand that so that we, that we can address all of these major environmental challenges that we're all facing now.

>> Well in the interest of kind of wrapping this up, do either of you have any parting comments on what can, what can I do? What can a listener do to help promote this and spread the message. And Jim, you've already alluded to that a bit. Go talk about it with the people that are part of your everyday life. Because it matters.

>> Yeah, one of the main messages, certainly that's the case. But we need everyone to join these country regional support groups. And not only country but state support groups or county support groups. And so what would be important is for everybody to stay tuned to the website. And I'll leave that to Barbara to guide people how to get there. But those websites and those storage places will be places for people to obtain messages and materials that they can take to the chamber of commerce and the rotary clubs and then together locally and decide on messages that are appropriate for your own community. Barbara, you want to explain that website deal?

>> Yes, we would love to have you use our IYRP.info website. And we would love you to contribute to it. If you have stories to tell, if you're willing to do a little video clip that we could include in our rangeland voices. If you have photos to share that you want to share of some beautiful rangeland landscape and demonstrating some ecosystem service. We have a photo archive. We have a video archive. And we hope you'll go and enjoy those but also contribute to them. And on the website as well are the links to our social media. And of course, if you're involved in social media at all, we'd love you to go in and become a friend and like us and share us. And so I think there's lots of ways for us to collaborate and share our own stories. And we hope that our website, again, will be one of those, the main mechanisms for distributing that information. So keep watch of that. I think Tip is going to be doing some more podcasts so you'll get some updates. And we look forward to being a part of this, of having all of us be a part of this effort.

>> We will do that. And we'll have a number website links on the show notes section of your episode description, including the main International Year website as well as some websites that are not quite so easy to find but that are also important. Jim and Barb, thank you.

>> Thank you, Tip.

>> Thank you, Tip. We appreciate your being a part of this.

>> We certainly do, very much so.

>> Thank you for listening to The Art of Range podcast. You can subscribe to and review the show through iTunes or your favorite podcasting app so you never miss an episode. Just search for art of range. If you have questions or comments for us to address in a future episode, send an email to show@artofrange.com. For articles and links to resources mentioned in the podcast, please see the show notes at artofrange.com. Listener feedback is important to the success of our mission, empowering rangeland managers. Please take a moment to fill out a brief survey at artofrange.com. This podcast is produced by Connors Communications in the College of Agricultural, Human and Natural Resource Sciences at Washington State University. The project is supported by the University of Arizona and funded by the Western Center for Risk Management Education through the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

>> The views, thoughts and opinions expressed by guests of this podcast are their own and does not imply Washington State University's endorsement.

[ Music ]

Main IYRP website

Introduction to the IYRP (Video)

Pastoralism is the Future (Video)

Who are pastoralists? (Word Cloud)

What are rangelands? (Word Cloud)

North American section of IYRP

Facebook IYRP Global

Facebook IYRP North America

Twitter IYRP Global

Twitter IYRP North America

Instagram IYRP Global