Is it time to surrender the Western U.S. to cheatgrass and frequent fire or regroup and work smarter? Jeremy Maestas, NRCS National Sagebrush Ecosystem Specialist, and Dirac Twidwell, range and fire scientist at University of Nebraska-Lincoln, present the Defend the Core framework for invasive species management, a fresh approach that prioritizes preventing degradation where intact, functional plant communities exist and reducing risk of invasives spreading from areas already compromised. After a hundred years of trying to understand invasive plant dynamics, we now recognize that preservationist passive management will not cause degraded plant communities to return to a reference state. This episode, part 1, describes the problem and introduces this new approach to risk reduction. Come back for part 2.

Transcript

[ Music ]

>> Welcome to the Art of Range, a podcast focused on range lands and the people who manage them. I'm your host, Tip Hudson, Range and Livestock Specialist with Washington State University Extension. The goal of this podcast is education and conservation through conversation. Find us online at Artofrange.com.

[ Music ]

Welcome to the first in a two-part interview Jeremy Maestas and Dirac Twidwell on the Defend the Core Framework for Invasive Species Management. If you have not already, please subscribe to the Art of Range through your podcasting app to stay up to date with new episodes.

[ Music ]

Welcome back to the Art of Range podcast. My guests today are Jeremy Maestas and Dirac Twidwell. Jeremy is a Sagebrush Ecosystem Specialist with the NRCS and the Sage-Grouse Initiative. And I'll let him say more about this role in a minute. Dirac is a Range Scientist at University of Nebraska, Lincoln, who works primarily in grassland ecosystems there in the Great Plains. They've both been attached to the Defend the Core Strategy for dealing with problematic invasive species on rangelands. Jeremy and Dirac, welcome.

>> Hey, thanks Tip. Glad to be here.

>> Yes, thanks for having us.

>> We're -- we're here to discuss this big picture framework of how to deal with invasives, but because it's a really important topic, I want to make sure that listeners who don't know either of you, know who they're listening to. So Jeremy, let's start with you. What is your current professional role in range management and what led you there?

>> Yes. So, my background's actually in wildlife biology, but I spent most of my career doing rangeland ecology. So, that's how I think of myself now. And I work for NRCS's West National Technology Support Center, which is our science and technology arm of the agency. And I work across the western U.S., helping put science into practice, and collaborating with scientists from Montana to Nebraska, which is why Dirac's here.

>> And Dirac, how did you end up working on grassland conservation in the Great Plains? Are you from Nebraska?

>> Actually, yes I was born in Nebraska, and in a town of North Platt, kind of west central Nebraska, and you know, we moved out of the state when I was three, and grew up mostly in Missouri. And you know, it's one of those things like in Missouri and as you go east, there's more fragmented landscapes, and we just happened to be coming out into the Great Plains more. You know, my father and I, whether it was pheasant hunting or you know, heading into Kansas or back to Nebraska and so forth, and there's just something about wide open spaces, the horizons, and the openness of it that was always really attractive to me. And so, yes, I did my graduate school in Rangeland and Fire College at Oklahoma State with Sam Fuhlendorf. Then did -- went down to Texas A&M and -- so, I've just been fortunate enough, really throughout my whole training, to be able to really train and work throughout the entire Great Plains now. And you start to realize as a professor, that becomes pretty unique. Often we go where the job takes us, and so, I've been fortunate to be working out here in the Great Plains with landowners now for, oh I guess it's been 15 years. So, it's been really enjoyable, all starting just from having some trips and going, "Wow, look at the landscapes. This is -- this is different. This is special."

>> Yes. As I've mentioned before, I grew up in northern Arkansas in the Ozarks and I had not heard the term "rangelands," even having done some internships with the Corps. of Engineers, with a wildlife biologist and wildlife biology was initially my interest until I came to Idaho and found that rangeland ecology was more what I was interested in. Well, it feels awkward sometimes to state the obvious and say that invasive annual grasses are a problem on western rangelands, and I think we'll begin with that, and then move over to woody species encroachment. It's sort of like getting excited about telling someone that the sky is blue, and why it's blue, and why that's -- it's actually important. But sometimes it is important to speak the truth, to let it sink in, or see it in a new way. And I -- it was a bit of that kind of a-ha moment when I read the articles initially in the special issue of Rangelands. I think it was the June 2022 issue. I read it a few months back. And again, more recently reading the special issue of REM, Rangeland Ecology and Management. But I felt like I saw it again in a new way, in terms of the scope and the depth and the reach of the problem. And it's -- I guess what I'm saying is it's not a topic that we have the freedom to just get over it. To say it's here and we have to get over it. We might get tired as a culture of talking about opioid abuse or suicide, but we can't ignore it, or quote, "move on." You know, these things are in our faces, and we have to keep at it until we begin to get to the roots of these chronic, far reaching, in many cases destructive problems. And invasive annual grass kind of feels like a cancer of rangelands. I am aware that some people say it's good spring feed, but I don't know. This still feels like the fox who can't reach the grapes, and so he convinces himself he didn't really want them in the first place. Pretty little grass plants are still preferable. So, we're -- yes, we're talking about a framework, an overarching framework for conservation and triage and repair. And maybe the starting place is, you know, what is the scale and significance of the problem? And if it's here to stay, you know, what's left to talk about? Why do we need a new strategy for conserving rangelands?

>> Yes, I can kick this off here. Thanks, Tip. I mean, the topic of invasive annual grasses has been on the brain of rangeland scientists for a long time. Aldo Leopold Sand County Almanac has an entire chapter called, "Cheat Takes Over." This is not a new problem, but for some reason, the profession has in large part, just learned to live with it. And perhaps maybe that's because we've not been that successful in managing it in the past, or you know, we've found other ways to justify its value. But one thing's happened in the last seven or eight years that's really transformed how we're thinking about rangelands broadly, and that's really breakthroughs in technology. Remote sensing based vegetation maps. You've done episodes in the past on the Rangeland Analysis Platform, or RAP. You know, those products and their innovation in the last few years, has really made it hard to hide that what we're doing to conserve range lands as a whole isn't working. And what I mean is, if you zoom out and you look at the status of rangelands as a whole, they're being converted into these alternative states that are a lot less functional for the ecosystem services and values that we care about. Whether that's due to an invasive annual grass out in sagebrush country where I work primarily, or whether you're out in Dirac's backyard in the grasslands of the Great Plains where species like Eastern Red Cedar are consuming entire biomes. So, I attribute a lot of our awareness and emergence of this new strategy and how we're thinking about tackling the problem to just the pace and scale of these large-scale, biome-wide ecosystem threats that are collapsing our rangelands. So, we've spent a lot of time in the range profession, perfecting grazing management and talking about manipulation of plant composition at local scales, but I joke sometimes that we failed to pick our head up and look across the horizon and see what's coming. And so, if you zoom out, you know, there's just a lot less rangeland to be managed as it transitions to these invasive species. And so, there's some brand new work out in Rangeland Ecology and Management, the January 2023. Andy Kleinhesselink did an analysis looking at all of the BLM allotments in the west using RAP data and essentially gave us a land health check to see how those allotments were doing and -- the single largest pattern observed is the transition of -- of these rangelands to invasive annual grasses at such large scales. And so, this is something that really brings me back to like you know -- we should be asking ourselves, "Are we just rearranging furniture in a house that's burning down?" And by that I mean, when we're working at a scale of a pasture or a ranch, you know, is that an exercise in futility if we don't address these other large-scale issues that perhaps we've ignored or given up on? And that's a broader challenge for the range community.

>> And then it does seem like there's some you know, chicken and egg problem there as well. You know, what is the cause and what are the effects? You know, when we say large-scale stressors, it often feels like cheatgrass is the stressor, but is -- so is cheatgrass moving in, in response to things that are otherwise stressing the plant community, or is cheatgrass moving in otherwise resistant, resilient ecosystems, and then cheatgrass is the stressor?

>> Oh, that's a fantastic question. I'm not sure we know the answer. But I think I have an--

>> Probably yes and yes.

>> -opinion. I'm going to bring Dirac in here because even though he's not a cheatgrass expert, I think he's seeing some of the same patterns with woody encroachment and Dirac, maybe I'll tee you up to talk a little bit about this vulnerability concept and the idea of not just focusing on, you know, the sensitivity piece of the equation, but really you know, exposure to these invasive plants.

>> Yes. Tip's question is a really great one. If -- you know, I was fortunate enough to study in an invasion ecology lab during my PhD, and really whether you're talking about woody encroachment overall, or you know, herbaceous invasives, it's all a biological process and so, when you're asking is it, right, the stressor or is it a symptom of what's going on in the landscape, the answer's going to be yes, right? The complex feedback's playing out, a result of all of it. I mean, we're talking about novel change, and there's a lot of changes going on in ecosystems. And the question is just, "Well, how do we take our understanding of these systems and start to adapt and do a better job?" And when you're sitting here asking questions like, "Why do we need a new strategy?" and you know, it's because we don't have large-scale success stories that we can point to, that have been able to successfully navigate collapse at these scales. When you're talking about cheatgrass invasions, you know, woody encroachment, good like in the scientific literature and finding demonstration sites where we can walk out there and say, "We were able to withstand this kind of scale of collapse." And that's because our -- there's weakness in our range management paradigm. And this has taken advantage of those weaknesses, especially multiple different invasive species. Biologically speaking, right, invasive species spread through a reproductive pathway, and when you think of something as simple as a non-resprouting juniper species, all of our decades of studying it were basically how to remove trees with Tonka toys and mechanical or chemical means. It spreads through seed, and we didn't even you know, go down the kind of depths to study, like, "Well, how do we actually manage how it reproduces?" So, if you're a basic biologist, that's one of the fundamental things you would look at. In rangeland ecology, because we didn't think of how it spatially spreads, right, and how it moves in landscapes, we just -- we wait until there's a lot of cheatgrass, or wait until there's a lot of brush, or wait until there's a lot of cedar, then we could help ranchers, you know, fight it. Well, of course, there's all that seed in the seedbank, so it comes right back. And you know, you study this, like how we move animals around, or our cattle, or our grazers, right? They're -- they don't stop these kind of state transitions. That's why -- that's why the rangeland profession shifted from a model of range condition in 1995 to a state transitioned base framework, because we want to avoid state transitions at large scales. So, when we came up with this vulnerability framework, it was to start thinking about how not to react to symptoms, how not to assume that how we managed in our principles of range that were started you know, decades ago, that were in different conditions and different systems, how do we start to actually get ahead of these kind of changes today? And so, this vulnerability framework, we borrowed it from scientists and it's a well-known concept and framework for navigating global change. They even use it for like you know, some of the climate change and global change pressures tied to wildlife. We adopted that same framework and it's really simple. What drives changes in the sensitivity of your rangeland? What drives the changes in the exposure to threats in your rangeland, just think of those two buckets and how do you manage that? Are rangelands becoming more or less sensitive to change? And there's a number of factors causing that. And usually, that's where we spent most of our management efforts is on the sensitivity box. You start thinking of exposure. Something as simple as, right, like how -- where does seed dispersal come from for things like cheatgrass, or mesquite, or Eastern Red Cedar? And it was actually working with the School Land Trust in Nebraska where they were asking me, "Where can we -- what can we do right now, given you know, the collapses that are occurring and we're losing revenue for public education on school and trust areas here?" And I was like, "Well, wait a minute. Where's the seed source coming from?" It's coming from, you know, a windbreak that was planted 30, 40 years ago, that's on your property, or that's on a neighbor's property that now you're managing that spread. So, we never really took it seriously how important exposure was. Man, I tell you, when we think of invasive species at large scales, that's what -- that's what we missed in the range profession. It is coming from a seed source. And if you don't manage that seed source, even our treatments are less important. The Flint Hills of Kansas burns 2 million acres a year, and the data shows that they're losing over time, because the Flint Hills of Kansas is becoming increasingly fragmented by seed sources. So, a tree escapes fire damage, right, or it escapes a treatment. It just keeps closing in on us. So, yes, Jeremy's point on here of like just what is it that we're missing, like yes, there's all these complexities, but we're just not managing risk well. We're still -- we're still doing a good job of utilizing our rangeland, but we're not managing risk the bigger risks. And we've missed some of the things that are fundamental biology that would help us do that better. And I think that's going to be the keys to success long-term, is just you know, trying something different at scale because what we've been doing hasn't been working.

>> Yes, I wanted to quote from one of the articles, the Chad Boyd article on "Managing for Resilient Sagebrush Plant Communities." Getting it -- I still feel like we're a bit in this place where we're trying to decide whether we just accept this is the new normal, and only mitigate for catastrophic wildfire risk, or do we attempt to do something useful? And I think -- I think the Defend the Core Framework is a really good way to get at that. But Chad frames the question or the problem this way. In the introduction he says, "The invasion of western U.S. rangelands by invasive annual grasses presents a challenge of generational magnitude to contemporary rangeland managers, scientists, and governmental authorities." The size of the annual grass problem is currently measured in tens of millions of hectares, and is growing. Equally daunting is the complexity of the problem. Sagebrush landscapes are characterized by strong variability and precipitation, temperature, elevation, aspect, and soil factors, creating an ecological maze of interactions for scientists and managers to disentangle. As invasive annual grasses spread across sagebrush landscapes, there are strong and lasting negative impacts to a myriad of ecosystem values and services, including forage for livestock, wildlife habitat, human safety, and loss of structures to wildfire, and rangeland carbon sequestration." In this issue of fires, the one that I sense is beginning to -- the combination of invasive annual grasses and fire, you know, is not a new problem, but I sense that at least among people that have more of a preservationist mindset, that the idea that if we just leave it alone, and it's going to automatically, on its own, you know, revert to you know, what I call some pre-Columbus, ecological nirvana, isn't going to happen. We're going to have to do something, you know, both to protect the places that still are functional, and to do something to mitigate the risk, manage the risk in the places that -- that have already been converted to it, a great and stable state. What -- how do we go about thinking, "How do we manage in these different contexts?"

>> Jeremy, I don't know about you, but this just -- it just sounds like where we started, you know, bouncing things back and forth, from the Great Plains to the Great Basin, and that whole idea of you -- I mean, we can see the spread of annual invasives of, you know, woody plan encroachment. I mean that's what -- that's what led to the whole discussion at that Idaho Cheatgrass Challenge, for example. And just where some of the mantra started to take off a little bit more. I mean, you want to talk more about that?

>> Yes, and give a little -- little historical background on this Defend the Core phrase and strategy that's you know, spreading quickly. It really started, you know, if I back way up, you mentioned connection I have with our Sagegrouse Initiative efforts in sagebrush country. You know, that started in 2010. We're 13 years into that. And we've evolved quite a bit from that species-centric view, but we learned in the early days, the importance of spatial targeting, we call it. In other words, finding out where most of the grouse life in these core habitat areas. And focusing our efforts there rather than trying to provide palliative care to some dying population on the fringe of the range. That was an early lesson learned that you know, the wildlife community adopted fairly quickly and embraced this idea of focusing in those core habitat areas. But in the last four or five years, we've started to connect with folks like Dirac, working across you know, diverse biomes, and now our team, we call it The Working Lands for Wildlife Team, has two big frameworks that guide our actions for both the conservation of the Great Plains grasslands, and the sagebrush rangelands of the intermountain west. And it was really in that context where our team was discussing and sharing struggles and challenges and lessons learned that this idea of spatially mapping out the condition of the land to develop a more informed and proactive strategy came from. Again, none of this would be possible without the breakthroughs and remote sensing vegetation data that's allowed us to see this for the first time. And so, you know, in my neck of the woods, I think it's fair to say, in the Great Basin, a lot of people assume we have to live with cheatgrass forever, everywhere. But the reality is, when you zoom out and you look at that with the data we have, about 70% of the rangelands, sagebrush rangelands, still have a very low or maybe even no invasive annuals. It's the other 30% that are heavily impacted. So, there's a tremendous amount of variability in the degree of invasion. Same thing in the Great Plains. You go from the south to the north, quite a bit of variation in the degree of woody encroachment. And so, that perspective has allowed us to deploy, you know, some new strategies to not just always react and run to the places where the crisis is worse, and try to think about what could we do today in those places that are still healthy and relatively uninvaded or uninvaded entirely, and keep them that way? You know, it's like the old "Ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure," but put into a map. Spatially explicit and helping us to think about, "Where would we start if we had a choice?" And that -- that's kind of some of the -- the initial background that led to really the first application of this concept, that you know, was tangible in our part of the world, through the Idaho Cheatgrass Challenge that Dirac mentioned, where you know, the NRCS leadership there, along with their partners, reached out and you know, Idaho's kind of Ground Zero for the cheatgrass fire cycle problem every year, dealing with it, you know, along that corridor there in Snake River Plain. And they're just tired of getting their butt kicked. And said, "What else could we do? What's a new way of doing business that it would give us a better chance of getting ahead of this problem?" And so, you know, we brought -- I brought Dirac over. We sat down with partners there and we really took some of these early conceptual ideas that NRCS had been, you know, trying to embed within our frameworks. And so, "Well, let's put the -- in the paper and see what this looks like specifically in tackling in base of annual grasses across the State of Idaho." And so, that really codified this concept of you know, if we had a choice, we'd prefer to identify our healthy rangelands that have low or no invasion of annual grasses, and believe it or not, those places still exist in Idaho. And we would like to anchor our conservation efforts there before we move out and try to do the more difficult task of restoring whole -- large areas that are already further along in that invasion process. Of course, this is the exact opposite model we currently employe which is spending hundreds of millions of dollars on fire rehab, chasing the problem. And so, what we're talking about here is totally flipping the script on our past approaches, by first going to these most intact, functioning rangelands that we can identify with data, and then, establishing those cores that we're going to try to prevent further invasion, do early detection and rapid response to keep it out, and then aggressively manage that invasion front that's coming our way. Rather than initially just running to the most degraded areas on the landscape and trying to put Humpty Dumpty back together again.

>> Yes, I like the analogy of the human health. You know, just like the most effective whole health approach is to maintain the inherent resiliency of the human body against disease, you know, both from external pathogens and from chronic internal dysfunction I guess, to have healthy tissues and organs and immune systems and that -- that thing, that whole system, is pretty robust. And so, it's worth spending a fair bit of effort in prevention because it's way more cost and energy effective than treating a problem once the body is unhealthy. I think that really does work well on rangelands because the places that are intact are much less vulnerable, I think especially with the way that we do land management today. I think some of the historical stressors, particularly you know, really heavy growing season grazing, is largely not there. And I've seen some fairly low elevation shrub step rangelands in Washington State that have withstood some pretty significant stressors because you had all of these plant functional groups that were still present. And the ecosystem still functions.

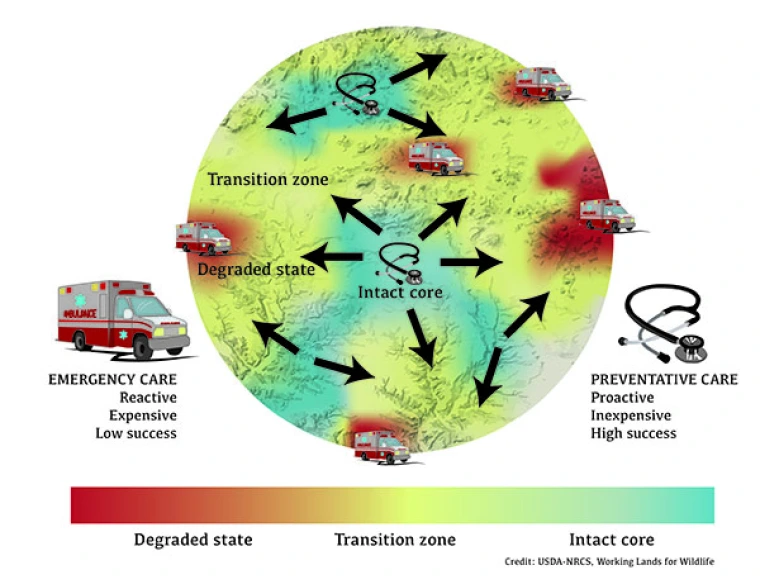

>> Right, and yes, you know, like going back to what Dirac was mentioning, it's the two-step of you know, managing that sensitivity of the land. In other words, in our part of the world, your perennial bunch grass is making sure they're healthy and abundant. But it's also the exposure, you know? So, if you're not exposed to the disease, your likelihood of succumbing to it is very low. So, you know, how are these seeds getting here? What are our roads and vectors? And how is that being brought in? And so, we're starting to have those conversations now where you know, maybe we hadn't in the past. And it's funny because with this health analogy, you know, I'll credit Dr. Dave Naugle at University of Montana for the -- they call it the Ambulance and Stethoscope Graphic. It's kind of our way of visualizing the Defend the Core concept that uses literally this, you know, these icons on a map to say, "There's these intact core area places on the landscape that you know, we can do preventative care in, and proactive management and try to keep the land healthy and not exposed to these invasive species. And then on the other end of the spectrum, there's these heavily degraded areas where you know, the ambulance, you know, the patient's already in the ER, and we're trying to administer life support. And then of course, you know, the in between stuff, right? The transitioning zones. But you know, that -- that concept, I guess I want to kick it over to Dirac a little bit, because he uses this term, spatially contagious. And it's really an important theme that these problems are really contingent upon what's happening in that surrounding landscape. Dirac, I don't know if you want to expand on it anymore?

>> Well, it's -- using this human health concept as an example, right? I mean, and my wife works in the health profession. I mean there's some things that are so severe that you will then live with it the rest of your life. So, we want to prevent those. Otherwise, it changes your way of life. There's a bunch of other health conditions and so forth that we can manage. So, in rangelands, you know, there's even a bunch of invasive species that we can manage locally. You know, in the Sand Hills, I always give an example of you know, you get these localized blowouts. Well, we manage them when they're local, but if you get spatially contagious, you know, destabilization of rangelands, well that results in the Dust Bowl. That changes our way of life, affects every citizen. So, it goes back to there's only a special few types of species and plants that cause these big state transitions at large scales. So, it goes back to scale, right? Like you don't want these at these scales, and when, you know, talking with the Nebraska Sand Hills, they're -- they're adamant, right? Like, "We have 100% adoption if planting Eastern Red Cedar." Ranchers were told it was the best thing they could ever do to their kid -- for their kids, right? Like, and for future generations. And that's because it's a local improvement that has local benefits. But you don't want that local improvement to take over the whole region of the Sand Hills. And they're of course saying, "But we've been told over and over again, it won't spread from here." I mean, do you realize how hard it was to even get these trees established? I mean, it was so much effort. Nobody could imagine it would start to spread and everything else. And the point was, is that the Sand Hills' resilience hasn't been tested yet. So, when we can map out the scales of these transitions and how they're collapsing, and we do this in the Great Plains, you can see the collapse of the Great Plains to woody dominance in a biome scale. At a large enough scale, only the Flint Hills has made it flinch. And they're losing because now they're surrounded. And so, their resilience of their management systems being now tested and pummeled and bombarded for the first time. So, when you think of that quote from you know, Chad Boyd that you read and everything else of where do we try and resist change, our most intact rangelands are where we have the best shot, because they've resisted the pressures from last century. The question is, is now the resilience of the systems are going to get tested this century. So, we shouldn't rest on our laurels thinking that just because they escaped last centuries, and they've withstood some, that they're going to be able to deal with the bombardment of things like annual invasions, and things like woody encroachment as this goes forward. And that was the story for places like the Sand Hills. As I went to South Dakota several times in the last six weeks, we can see the start of spread and invasion in those areas. And we did that with Idaho Cheatgrass Challenge, right? You run into the burning house, as Jeremy said earlier, because whoa, look at that. It's burning down. And of course, somebody's sitting there like, "Well, wait. The next houses are going to burn down. It's a spatially contagious process." That's what we see. So, you can actually point out in Idaho like, "Are we doing anything to prevent our best areas from losing," because look at this. You can see it creeping into your intact areas that don't have cheatgrass right now. And the rates might be slower, right, compared to other areas. It might be less sensitive, but we should really question if we actually think that they will not experience these transitions at all. I view that as a very dangerous assumption to make given the kind of changes today. So yes, the -- we can literally see it. We can see where places are more intact. We can see the opportunity ahead of us. And if we start to think about how to defend these areas, assuming that no one has really escaped this on the big issues, and just question, you know, maybe our pride and arrogance a little bit. Like, that was kind of where we went with the Sand Hills. And boy, I tell you, it's -- that's come full circle over a decade where, "Hey, like, we're starting to -- don't assume it's not spreading." We can look at it. We can point out the window and see it. And well, how do we now manage this better because we don't want the problems that other places have had. The same thing is true when you go to annual [inaudible] or anywhere else. So, yes. The ability to actually track this is huge. And now we have a corresponding strategy, and it's so cool. Not only a strategy, like a mantra of, "Hey, defend the core on these areas, because these are some of our last rangelands remaining that have escaped these kind of pressures." And then be more realistic about what we can do with large-scale change elsewhere. You know, mitigate those threats and more direct how we want to avoid certain consequences in those landscapes. So, I think that's what's needed. Like, we're talking about that with this kind of technology, we could have warned of the Dust Bowl. I mean, that's how I often relate to this in the Great Plains. Like that was a spatially contagious process that added up over time. And then bam, right? You feel the consequences of it. This is very similar to those playing out with invasive species.

>> Yes, it was really--

>> Yes, I've heard -- go ahead.

>> -oh. I was just going to add that -- a little more on the Cheatgrass Challenge experience, you know, sitting down with a group of statewide partners in a room, and having a map of the state up in various stages of annual grass invasion, and you know, challenging the group to identify where those cores would be that we could anchor conservation efforts in. And then, having this conversation about like, "Well, what's the preferred direction of management?" And so, we literally had one of the partners get up at some point and draw an arrow on the map, saying, "We'd start here in the core, and then we'd move out this way." I said, "Well, that's -- yes, that's the strategy." Right? It's defend the core first, grow it over time through restoration and more aggressive management of those more heavily infested areas, and then no one wants to give up on anything, right? And so, you've got places like the Snake River Plain that are heavily infested with cheatgrass. And so, we had to kind of talk about, "Well what -- what does it really mean there?" It's not necessarily a message of giving up, but it's more of expectation management. What's possible there in that place where if you -- if one ranch or one pasture created the most perfect postage stamp native ecosystem, but they're surrounded by the enemy or the problem, the threat, if you take your eye off of that for a few years, you'll probably lose it again, or you'll get burnt through because of all of the neighborhood effects. And so, what we talk about now is you know, mitigating the worst of the consequences of what's already happened. You know? And trying to minimize the impacts on life and property and the things we really value, because our decision space has drastically changed on what's -- what we could do in those -- in those regions. So, anyway, it was an interesting conversation that you know, we see play out in other geographies as we talk about this preferred directional management with starting in your cores, and moving out the other direction, which is again, against every bone in our body as resource managers because we've been doing the opposite for so long. In fact, how many people just wait until they're really sick to go see a doctor?

>> Right.

>> And we know we should go in for our annual checkups, but how many people really do it? And so, it's a bit of changing human behavior here, but it's what science, medicine, ecology are all teaching us is the more effective approach.

>> Yes, I think identifying the -- inside this framework, identifying good management or potentially effective management in each of the different strata, is useful. I've heard some criticism of this, you know, battle line analogy, because oftentimes those -- those in the, you know, natural environment, those eco-tons are -- can be pretty large. There's quite a bit of gray area. And you identify this and call it a transition zone in the framework. You know, we don't usually have a razor sharp line between the degraded state and the intact cores. The transition zone can be pretty large. And I would say there's quite a bit of variability in what, you know, what the species composition and plant community attributes could be in that -- in that transition zone. So, maybe if you've still got the time, let's talk about the ideas behind management. You know, what's the strategy inside of each of these three different zones: the intact core, the transition zone, and the degraded state?

>> Yes, Dirac, do you want to take a swing at this first?

>> Yes. So, there's a lot of things that we can do, and it beletts [phonetic] you know, any academic in me wants to answer that question, but in reality, this is a really practical then discussion. And so, we've literally started tying this to dollars. And there's two really easy indicators that we've started to use and that's just, "Okay, how much is it going to cost to treat this issue?" And when you start putting a spatial game plan together, those realities start to really hit you. And for any invasive species, right, it is expensive to manage invasions. And so, when you start putting a plan together, spatially, on a map, which we haven't done well. We haven't trained on that well. That's something that we need to do better in the rangeland profession, but you end up with the realities of scale. So, if it costs hundreds of dollars per acre to manage it, you know, in the -- that heavily impacted or that severely infested zone, right, your realities of scale change. So, okay, what are our goals in this given those realities of scale, because if we do this everywhere, right, it's just going to reinvade quickly, and we're playing Whack-a-Mole, and we're losing, and that's what we see long-term. And we're not getting the outcomes we want. And so, you start spatially targeting where you want to spend those more costly treatments. Now, as you get out in front of it, so let's go to the whole other side of the coin, I mean, wow. We never thought about this with like for example woody encroachment. I mean, we got data on how far ahead we should start managing seed dispersal and think about it before they become seed producing trees. In that zone, like there was a partnership between the U.S. Forest Service, the joint venture here at NRCS, and others. It came back as a contracted bid of $1 to $2 per acre when you were operating there, whereas it was hundreds of dollars an acre, even a thousand to $2,000 in steeper topography to operate a more severely infested zone. So, if you wait, you just can never catch it and we're losing. So, the idea is just the -- to me, it's an answer of scale, and that sets our objectives in what we can accomplish. And so, we work in some areas that you know, are part of now a woody dominated biome that used to be rangeland. In counties in those areas, they will identify these more local pockets. And this is where we have an island of Greater Prairie Chickens for example, pheasants, some of those things in a place here in Nebraska. They'll map out some of the existing leks and -- in the wildlife agency, and so forth. And then they'll look at this and say, "How can we anchor to those?" Draw those arrows just like what Jeremy described of Idaho and say, "Let's connect these," because our dollars per acre are going to go further by preventing the loss of these remaining, smaller scale cores and withstand that pressure. And then, "Oh, here's an area that's heavily infested, but right, the wildfire problem is growing because of the expansion of juniper species like Eastern Red Cedar here, volatile fuel. We're going to do strategic management around this city or neighborhood because we don't want houses to burn down." Like start doing fire wise there and maybe we can use some of the cropping systems here to prevent that? Just think about the landscape better. You're just -- your expectations have to be more realistic when you're in that heavy infested zone. And it usually revolves around just an economic situation, what we can do. [Inaudible] is like the Sand Hills, right? The short grass prairie. The Wyoming sagebrush step that pops on a map of what's intact. It's like the world is our oyster. Imagine if we acted now, but we've never prevented this. And that's why I was chuckling. Like, my doctor's telling me to exercise, eat better, everything else, and I'm like, "Yes, right," you know? We take it for granted. But of course, I'm then that person for -- in rangelands. And that's what you're seeing in Oklahoma. Oklahoma, states have come up with Great Plains Grasslands Initiatives. In Oklahoma, they have different regions that are their last grassland regions of Oklahoma. Here's where we're going to anchor to in heavily infested zones. Here's where we've got larger pockets. And yet to me, the strategy's the same. The treatments are just where you put them on a map and the economic realities hit you when you're dealing with this issue. And we -- if somebody wants to use prescribed fire to manage a fire sensitive tree in an area, right, they can manage multiple stages of the encroachment or invasion process. But if another group doesn't, they're coming out and doing hand-cutting before it becomes a seed-producing tree out from the windbreak. Maybe they're haying. Maybe they incorporate goats, right? Like you have more options if you act early. But if you wait, you're tied to really expensive mechanical and/or prescribed fire on this issue here in the Great Plains. The same thing's going to be true with invasion. It's just how to spatially target a spatially contagious invasion process, given the realities of the economics of rangeland. And that's literally where we're at now--

>> Yes.

>> -in this process. Like, Jeremy would say that's what we're actually building. I mean, we're changing the mindset in terms of how to target, how to plan. We held a big partnership workshop on this in Nebraska to do a planning process on how to target treatments for the Great Plains, and so, that's what we want to have in two years, are actual examples of how to better solve this issue by just planning, targeting, and being more realistic with our money. Jeremy, what do you think? I mean, right, like that's--

>> Yes.

>> -this is kind of the state of the art question.

>> You always have a great way of zooming out and articulating that, which is fantastic. And I'll circle back to Tip's maybe more specific question about with -- with invasive annual grasses, you know, what does this look like across these varying levels of transitioning rangelands? And this is why partly I'm super-excited about this. Having this kind of spatial, the explicit gameplan. It helps us finally put some context around all of these land management practices that we debate and talk about. We want to try to put the right practices in the right places, and like Dirac said, when your core areas, you have an uninvaded area or a relatively intact area, you have all the tools in the toolbox. We still have a lot of options. Eradication is still an option. I'd point to you know, probably the greatest example we have is sagebrush country, this -- this started long before we had any fancy branding of Defend the Core. There in Sublette County, Wyoming, Julie Kraft and Weed and Pest District and partners have been working around Pinedale, trying to keep cheatgrass out of an entire county. And so, you go to those rangelands and they're uninvaded except for along some -- the [inaudible] corridors and places where the plants have gotten a foothold. And so, they have you know, they're treating their vectors, their roadways, they're surveying intensively for early invasions that they can address. The patches are small where they do treatments and typically still have an understory of vegetation, so they're not having to get into costly receding and rehabilitation efforts. As you lose more ground though, and you start to transition to you know, the site has been invaded. There's a seed bank you know, this is where things get more challenging, and I think Dirac's always done a nice job of articulating this -- the myth of restoration, which is that we can like go in with a one-time treatment and be done. And it's quote, "restored." When you're dealing with an invasive species who's driven by seed, you know, we have -- we have to treat that seedbank. And so, in these transitioning areas, we're talking about multiple interventions, likely multiple treatments, over you know, several years. Probably going to need some kind of seeding and a more aggressive restoration practices in some of these areas where you know, patches of vegetation have been completely replaced by invasives.

>> This concludes the first in a two-part interview on Defend the Core. Be sure to stay tuned for the second episode, which will be Episode 100 for the rest of the story. Thank you for listening to the Art of Range podcast. You can subscribe to and review the show through iTunes or your favorite podcasting app so you never miss an episode. Just search for Art of Range. If you have questions or comments for us to address in a future episode, send an email to Show@artofrange.com. For articles and links to resources mentioned in the podcast, please see the show notes at Artofrange.com. Listener feedback is important to the success of our mission, empowering rangeland managers. Please take a moment to fill out a brief survey at Artofrange.com. This podcast is produced by CAHNRS Communications in the College of Agricultural, Human, and Natural Resource Sciences, at Washington State University. The project is supported by the University of Arizona, and funded by the Western Center for Risk Management Education through the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

>> The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed by guests of this podcast are their own, and does not imply Washington State University's endorsement.

[ Music ]

Rangelands journal special issue, "Changing with the range: Striving for ecosystem resilience in the age of invasive annual grasses".

SGI blog on invasive annuals in sagebrush country: https://www.sagegrouseinitiative.com/defend-the-core-fighting-back-against-rangeland-invaders-in-sagebrush-country/

LPCI blog on Woody encroachment in grasslands: https://www.lpcinitiative.org/defend-the-core-fighting-back-against-woody-invaders-on-the-great-plains/

NRCS WLFW Frameworks for Conservation Action: https://www.wlfw.org/

WAFWA Sagebrush Conservation Design: https://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2022/1081/ofr20221081.pdf

Western Governors Association Toolkit for Invasive Annual Grass Management: https://westgov.org/images/editor/FINAL_Cheatgrass_Toolkit_July_2020.pdf

Idaho Cheatgrass Challenge: https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/programs-initiatives/eqip-environmental-quality-incentives/idaho/the-cheatgrass-challenge-idaho

Kansas Great Plains Grassland Initiative: https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/conservation-basics/conservation-by-state/kansas/ks-great-plains-grassland-initiative

Guide for Reducing Woody Encroachment in Grasslands: https://www.wlfw.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/E-1054WoodyEncroachment.pdf

NCBA Cattlemen to Cattlemen episode on defending the core: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EpsJnM-IrPY