The giant bathtubs off the western and southern coasts of North America contribute large amounts of heat and moisture to the continent, driving much of the climate (long-term) and weather (short-term) of the Western United States. And oceans have regular oscillations in temperature, which drives moisture delivery. Researchers looked at historical yearling cattle production data going back to 1939 at the Central Plains Experimental Range to see whether correlations existed between the Pacific Decadal Oscillation and the El Nino Souther Oscillation and cattle performance. Interactions between the PDO and ENSO have an effect on both rangeland production and livestock weight gain. Listen to this panel discussion with Drs. Justin Derner, David Augustine, and EJ Raynor to learn more.

Transcript

>>Welcome to the Art of Range, a podcast focused on range lens and the people who manage them. I'm your host, Tip Hudson, range and livestock specialist with Washington State University Extension. The goal of this podcast is education and conservation through conversation. Find us online at artofrange.com.

[ Music ]

Welcome back to the Art of Range. We're going to talk about some pretty interesting research on the relationships between climate and cattle production this morning. My guests are EJ Raynor, David Augustine, and Justin Derner. All of them range scientists that have been working in Colorado. Good morning, guys.

>> Good morning.

>> Good morning.

>> Good morning.

>>I think we'll take a minute to have each individual person introduce themselves and describe a bit what they're doing now and how -- what was your pathway to being a range scientist. EJ, we can start with you.

>>Well, I had a passion for wildlife and was able to conduct a research study in Kansas, in Manhattan, Kansas with plains bison and evaluating their response to fire frequency at Konza Prairie Biological Station. And with that work, I found a passion for tackling applied questions and then rangeland management that's very much a main topic is tackling applied questions. And so since I conducted my dissertation work on bison, I've been working in rangelands across the Great Plains from Kansas, Nebraska, Colorado, and currently, I am a new grazing lands scientist with Colorado State University's AgNext, collaborative for sustainable solutions for animal agriculture. And our mission is to identify and scale innovation that fosters the health of animals and ecosystems, promote profitable industries, as well as support vibrant communities.

>>That's a mouthful, but I like the goals.

>> Thanks.

>>Justin, good morning. Why don't you introduce yourself?

>>Good morning, Tip. Justin Derner. I'm a rangeland scientist associated with the Agricultural Research Service. I was born and raised on a ranch in the Nebraska Sandhills and then decided to go to the University of Nebraska for my undergraduate. And while there, I was able to work on some graduate student projects and their mentorship helped me decide to pursue -- or excuse me, graduate degrees and I went to Oklahoma State University, and then to Texas A&M University, completed up my degrees and started working for the Agricultural Research Service in 1998. And spent five years in Temple, Texas and moved to Cheyenne, Wyoming in 2002, and been a research scientist here since that time.

>> Great. Welcome. David.

>> Thanks, Tip. Yeah, I am currently a research ecologist with the Rangeland Resources and Systems Research Unit with Justin based out of Fort Collins, Colorado. And I came to range science much in the same way that EJ did. My interests growing up were mostly in ruminants, wild ruminants, and grazing ecology, but I started working in forests for my master's degree working with deer. And then I did a PhD, working with a suite of wild ungulates on a large ranch in East Africa, where I was looking at cattle interactions with wild ungulates. And that's what led me into the rangeland world. And from there, I moved to the Great Plains. About 20 years ago, I've worked on a number of the national grasslands. I started off as a wildlife biologist with Comanche National Grassland in Southeast Colorado and then moved over to ARS, and I've been working in the western Great Plains for, like I said, the last 20 years.

>>Great, welcome. Well, I feel like a broken record at this point saying that variability in precipitation, timing, and amount, and other climate factors are stronger drivers of vegetation change on rangelands than just aridity. And as Jeff Herrick, the Jornadasoil scientist, has said there's three things that set pretty firm sideboards on what is -- on ecological potential, certainly biological or botanical potential. Those things are soil texture, depth to bedrock, and precipitation. You know, some soil attributes change at the plant soil interface, some. But the general -- you know, the general composition of soil particle types and the parent material they came from doesn't change much, and for sure, not quickly. But I still think we underestimate the significance of precipitation variability on the really obvious thing like forage production, but also on species composition, you know, vegetation expression, and different successional trajectories. Your team has taken that one step further using some really long-term data to analyze climate variability and tie it to livestock production characteristics, not just net primary production. So I want to get to the details of that and have you describe this specific research project in a little more detail. But I think the first question I want to ask is, what's the history of the Central Plains Experimental Range where this work was done? There's long-term data, particularly high-quality data is pretty rare. And, of course, a little less than 100 years, really isn't all that long. Can one of you talk a bit about the history of this experimentation, as well as the long-term Agroecosystem Research Network?

>>Sure, I can start with that. So the history of the research stationbegins with the Dust Bowl, and it shares a common history with all of the national grasslands in the Great Plains. All of these lands were homesteaded by the end of the 1920s. But as you say, you know, the temporal variability and precipitation was just not understood at that time. And so we went from the wet '20s into the dry '30s. And the Bankhead-Jones Act is what -- was an act passed by Congress that allowed the government to purchase back many of the lands that had been homesteaded. And those lands that were purchased back by the government from the homesteaders are what were used to create the national grasslands. And when they created Pawnee National Grassland, they split off part of it and established the Central Plains Experimental Range, which is where the three of us have been working. And that experimental range was established in 1937. And in 1939, several of the scientists working there had the foresight to establish a long-term stocking rate study. And so one of their main objectives was to support the livestock industry in the area. And how do we assess -- address the question of how do we assess sustainable stocking rates? So beginning in 1939, they set up an experiment where they were grazing different pastures on the range at light, moderate, what they thought would be light, moderate, and heavy stocking rates. And that experiment has continued all the way to the present day. And so, yeah, the foresight and continuing that. And annually measuring the weights of the cattle at the beginning and end of the growing season within that experiment is what provided the dataset that we were able to work with for the analysis that you're referring to today.

>>Yeah, how did they define light, moderate, and heavy stocking?

>>It's not clearly stated at the time. They were running cattle out there so they had an idea of what was appropriate based on the condition of the range at the time. And then they just went -- the light became 50% below the moderate and the heavy became 50% above, just trying to bracket that range and see how do the cattle perform under these varying rainfall conditions from year to year at the different stocking rates.

>> Got it, yeah.

>> Justin, do you have any additional insight on that initial selection of moderate?

>> Yeah, Tip, I think one thing they were trying to do with the moderate stocking was to come up with a 40% utilization. And so as David mentioned, the light was about half that at 20% and the heavy at 60 in terms of the general aspects of the study.

>> Got it. And was there climate data being collected at the station as well? Or is that data that you use in the analysis coming from elsewhere?

>>Yes, on site, there's a climate station that has been collected since 1937.

>> Yeah, I've seen some charts. I don't remember what the -- was a relatively recent publication that covered some of this climate variability data. But one of the things that stood out to me is that I think of the variability of precipitation here a little bit further west, being pretty significant, but we also have a wintertime precipitation pattern and that tends to take out some of the variability. Back in -- I think it was 2000, 2001, I was on a -- an NCBA tour over in Kansas and we were there in June. And I believe that year, nothing ever greened up because there had been no precipitation since the snow left, you know, sometime in late winter, but early enough in winter, that it was definitely gone before the growing season came. The amount of variability that you experienced in the shortgrass prairie there on the western edge of the Great Plains seems to be more extreme than maybe anywhere else in the country. Is that the case?

>>Yes, I would agree with that. It is quite extreme here because our precipitation regime, as you say, it's mostly summer, spring and summer dominated, so we don't get much snowfall. And we can't rely heavily on knowledge of the winter precipitation to, you know, predict stocking rates that were going to work for the coming growing season. And just these past two years alone have really illustrated that. From 2021, our forage production was well above the long-term typical average around 30% above normal. And this year, it has been an extreme drought with virtually no production from our warm season grasses in the middle of the summer. And so that -- dealing with that kind of extreme fluctuation just in two years is the major challenge that our producers face here.

>>I think in the paper, you said that during that -- during the timeframe of, I think, 1939 to whenever the later date bound of the research was that rainfall varied from 88 millimeters to 513 millimeters. What is that in inches?

>> Goodness, three to --

>> Four and a half to 20 inches it seems [inaudible].

>> Three toa little above 20. OK.

>> Yeah, that is quite a range. I mean, a landscape that received 20 inches annually would look a lot different than one that received 4.5 annually. So if those are changing all the time. There's going to be a lot of listeners that have not been to Northern Colorado and are not familiar with the shortgrass prairie before we jump into talking about ocean temperatures and what that has to do with cattle in Colorado. Describe a bit -- describe the plant community there and kind of what the geography is.

>>I can do that. So I would describe this landscape as gently rolling. It's -- I mean, it is flat, not -- but not perfectly flat. So gently rolling uplands with occasional swales. And the landscape -- because we are dominated by warm season precipitation here in eastern Colorado, it's -- we're dominated by grazing tolerant and drought tolerant shortgrass species that are C4 grasses. So blue grama and buffalo grass are the two dominance in this system. And typically make up the vast majority of the forage production. However, we also have a C3 grass component, mostly western wheatgrass and needle and thread. And those are very much more productive grasses in terms of above-ground production. So they're also very important to the overall system. And as you -- so here, we're mostly dominated by the C4 shortgrasses. As you go further north into eastern Wyoming, further north into the plains, that's where you start getting more of a cool season component and more balance between the C3 and C4. So we are mostly C4 dominated here.

>> OK. Well, I guess to get into the research, if I'm trying to frame what you guys set out to do, it looks to me like you're trying to address this annual challenge of how to plan for proper stalking in such a variable landscape.Whatever we might mean by proper. I guess, if I was trying to, you know, spit ball somethingimproperis likely some variation around that 40% utilization or harvest coefficient. But, of course, if you stock in order to not be overstocked in the lowest years, then you're foregoing significant livestock production that otherwise would be sustainable. But it's also difficult to flex that much from year to year. And so my understanding of what you set out to do was to see, is there something besides weather forecasts that people can use to attempt to make some, you know, more scientific decisions on, say in April, attempting to get some idea of what's -- you know, how much variation then and which direction from average is the precipitation and, therefore, forage production going to be? And so you tried to see whether or not there were any correlations between these ocean temperature oscillations and in forage production and livestock production. A lot -- my guess is that I'm likely a decent gauge for how well other range professionals and the rancher community comprehend the Pacific Decadal Oscillation and whatever ENSO stands for. And it's not as much as I would like. So I think it would be really worthwhile for us to spend some time talking about these terms that are in the news. They're on the, you know, weather forecasts. We hear about them, but my guess is they're not very well understood. So, yeah, let's take a crack at trying to understand PDO and ENSO.

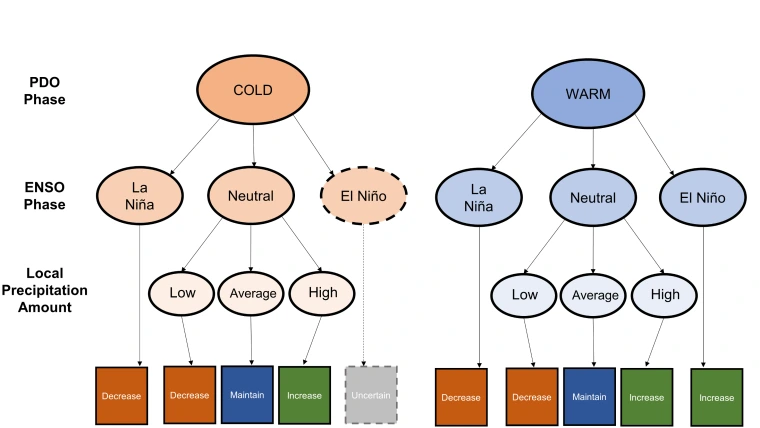

>> Yeah. Thanks, Tip. And appreciate the background there. For producers, it's largely looking at two large bathtubs. And both of those sitting off of the West Coast. One, the Pacific Decadal Oscillation, as the name implies, is off the Pacific Northwest coast and looks at the temperature of the sea surface water out there, whether or not it's warm or cold, and that water oscillates on a decade ormore scale. And so if we have a cold bathtub out there, less water is going to evaporate into the atmosphere and be carried in a jet stream across over to us. When the water is warm on the Pacific Northwest coast there, then more water, of course, finally could come into the Central Great Plains and give us an added potential for precipitation. That's on the scale then of a decade or more plus. Currently, we are in a warm Pacific Decadal Oscillation or PDO. So the chances in general are that we should have enhanced probabilities of more precipitation coming across the jet stream. The second main bathtub, if you will, for the producers is what sits on equator, the ENSO, E-N-S-O, or El Nino-Southern Oscillation. And that oscillates on a shorter timeframes, can be several months to couple years and is framed by the two terms, El Nino or La Nina. So when we have an El Nino phase, extra warm temperatures there on the equator, we have an enhanced probability of that water like in a warm bathtub creating steam. That water then can come in the atmosphere and come across from the southern side to the Great Plains. Conversely, when you have La Nino or the colder water there on the equator, our probability of that water coming off the oceans into the atmosphere then is reduced and, therefore, we have a higher probability of drier or drought conditions. So Tip, what we're able to do is put together a kind of reconstructed history of those patterns of the PDO, which, again, oscillates on more of a decade or more scale. And the El Nino, La Nina, the insole phases is they oscillate on a several-year phase and recreate history and their probability is how they influence forage production utilizing the long-term data that David mentioned that are Central PlainsExperimental Range. You put that together with some great collaborators, like Bill Parton at Colorado State University recreated, that we found some interesting patterns where the PDO when it was warm and when the La Nina phase when it's cold, that creates kind of a controversial effort. So you have a warm bathtub and a cold bathtub they meet in the middle and, essentially, you have to rely on current precipitation in the spring for accurate stocking rate decisions. Same sort of thing happens when you have a cold PDO on the northwest coast. And the warm El Nino situation on the equator, again, controversial and having to weigh on spring precipitation, but the odds tilt infavor of the producers when it aligns up with warm PDO and an El Nino warm equator situation, we have enhanced probabilities on both sides of extra precipitation coming in. And therefore, one can look at enhancing or increasing stocking rates with extra forage prediction -- forage production, excuse me, predicting, conversely, when you have both of bathtubs being cold. That is when you have a cold PDO and you have a La Nina on equator. That's a very high probability of low forage production usually occurring during major droughts as we experienced throughout much of the 2000s. And therefore, then producers should be in a prediction ability to look at reducing stocking rates when those phases align. So really, it's a matrix of putting together those four probabilities of warm or cold off of the Pacific Northwest and off the equator into a pretty simple decision tool for producers to use. And EJ's put that together for use with Colorado State University Extensionin a nice little brochure pamphlet for the producers. And that's being used on the shortgrass stuff today.

>>Yeah, that's really interesting. To what extent is the El Nino Southern Oscillation predictable? It feels like you often hear on the news, you know, El Nino might last a couple more years. But on the other hand, the -- some of these things are pretty predictable. In fact, I remember some climate scientists saying that the big drought of, I don't know, 10 years ago in the Southern Plains was predicted and the strength of it pretty much matched what had been predicted, and it was being predicted back in, you know, February, March, early enough we're able to make some decisions about it. It seems like the decadal oscillation seems a little bit more certain. What's been the regularity of the El Nino Southern Oscillation?

>> Yeah, Tip, I think what most of the things that we look at in terms of predictive ability, they've increased with time with increasing computer capacity and more data. The Climate Prediction Center does a fantastic job of putting out model ensemble predictions. So not just a single model, but composites of multiple models into what the El Nino Southern Oscillation signals going to look likeclear into 12 months out in advance. So we have a pretty good indication that currently we're still in the La Nino or cold phase for the third consecutive winter in a row. And it's causing major issues across the western US with the model ensembles predicting that moving towards a neutral situation in the spring. So producers at least have that positive outlook to look forward to and then likely an El Nino developing as we move into next fall already, Tip. So for us, the key thing is looking at that El Nino Southern Oscillation phase as it comes into the spring time for the producers. And this year, it'll be one of those where it's in the neutral phase. We're in a warm phase on the Pacific Decadal Oscillation, so producers will probably likely have to use the spring precipitation primarily as a driver for their stocking rate decisions moving into 2023.

>> Got it. Yeah. Well, we will provide that chart, which is a really useful graphic to try to chew on this and take some time to think through it. We'll provide that as a link on the podcast show notes. Let's come back to livestock production. Talk a bit more about the livestock production variable or variables that you were tracking in this historic dataset to try to understand these influences of climate.

>>Yes, so the main variable of interest was production at the end of the year, so subtracting weight gain at the end of the year from beginning of the year. And that's primary or secondary production, as we put it in from looking at trophic ecology, primary production, secondary production. Secondary production are the consumers of that plant material. And we evaluated data spanning from May to end of September. And the three different stocking rates have been moderate and white and assessed how they related to local precipitation, El Nino Southern Oscillation Index and Pacific Decadal Oscillation Index spanning from February to April before the grazing season. And that is the experimental setup in terms of our analytical approach.

>> Right. So all of our production measurements have been with yearling steers, I would add. So -- well, not all of them. They've either been with heifers or steers but all with yearlings. So we --

>> Yeah.

>> -- like currently, we typically get cattle coming to us, yearlings at about 600 or 650 pounds in May. And then we're trying to grow them to around 1,000 pounds in -- at the end of September, but those growth rates really vary depending on all of the variables that EJ just mentioned, as well as the stocking rate.

>>Yeah, that's interesting. You know, one of the criticisms ofag research sometimes is that because it's difficult to hold things constant at a field scale, we often do things at a very small scale and then try to extrapolate that. What is the scale of this study?

>>The scale of this study is spatially half section pasture, so about 320 acres in size. And the temporal scale is the growing season weight gain based off of the end of growing season, compared to the early growing season, so that's temporal scale.

>> Yeah. How has this information been received by folks that have the potential to use it?

>>Well, we could answer that separately. I would say my answer for the question of how it's being used is a manner to reduce uncertainty when making stocking decisions at the end of winter and purchasing the final number of head before the grazing season begins. So it's a method to reduce uncertainty when making stocking decisions that could be of financial interest you.

>>Yeah, I would add that I feel like the number one factor that most of the ranchers in our region really think about is last year's weather. So when you're coming out of a good year, people feel good and feel more confident about maintaining moderate or above moderate stocking rates. When you're coming out of a drought, people, you know, really seem to stock to last year's conditions. And that there is value in that, right, that -- because, you know, last year's conditions really do influence plant condition, but this adds a new layer of prediction to help get past that feeling of just relying on the previous year. I don't know how many -- how frequently it's being used right now because I think, like you said, a lot of people have uncertainty about what is PDO, what is ENSO, and does this stuff really work? And so I think it'll be important going forward to really evaluate how much predictive capacity there is, especially as these forecasts improve, like Justin just mentioned.

>> Yeah, Tip, I would add. I think one of the things that our work was trying to do was just help tilt the odds for producers dealing in risk in a very highly variable environment,as David showcased in the precipitation. Anything we can do to help them reduce that risk and increase their predictability in terms of knowing what the weather is likely to be in terms of trends helps them in terms of their decisions related to number of animals, long -- lengthy grazing season and preparing for potential drought or dry conditions, getting ahead in terms of our proactive manner.

>>An important aspect of this study's precipitation information used to inform our model and predicting livestock weight gain at the end of the season was that local precipitation spanning October to April of -- before a subject grazing season, were evaluated as well as PDO and ENSO starting in February to April of that year of interest. And this is found because these were the two temporal windows for ENSO and PDO to be important for forage production found by a previous study at the Central Plains Experimental Range. And 70% of forage production at the Central Plains Experimental Range is explained by late winter, early spring precipitation. And that's also the same time the final purchases might be made in a stocker enterprise.

>>I like the decision tree showing how these different PDO and El Nino Southern Oscillation combinations where they're in phase, out of phase, and how that interacts with more near term precipitation forecasts to potentially predict livestock performance forage production, and therefore, whether people should consider stocking up or stocking down. But I'm guessing that those patterns may not have the same effect in different ecoregions or plant community types. Has there been any effort to look at what these different combinations between PDO, ENSO, and local precipitation would look like in other regions of the country?

>> Yeah, great point, Tip. Elsewhere in the country, evaluations of soil moisture and precipitation have correlated these large scale climate modes PDO and ENSO to variability in those abiotic factors in -- for instance, in the Pacific Northwest, a La Nina spring would be ideal for forage production, and therefore, cattle waking or livestock waking. And so this is a phenomenon that varies depending on where in the country you may reside and could be extended through further work to create decisions for tools throughout grazing areas of the United States that was of interest.

>>Yeah. Are you aware of any efforts to do that or you're saying that could and should be done?

>> It could and should be done. Right now, we've been collecting datasets of light, moderate, and heavy stock pasture across the Great Plains to potentially tackle questions looking at these large scale climate modes. But those long-term, seven-decade datasets are quite rare throughout the Great Plains,and especially those that have been maintained in native communities, and instead have moved towards improved pasture locations at our experimental stations throughout the nation. And so the CPR dataset is relatively unique for providing insight on native perennial grassland management for livestock production. But right now, efforts to broaden the applicability of this tool are just at the stage of collecting other datasets at this point in other regions.

>> Got it. A related question that maybe you don't have the answer for. How many old research stations are there like this that have long-term data going back that far?

>>Well, in regards to livestock production, cattle production, very few. I think Justin Derner might be a better source for that answer. But to my knowledge, a long-term continuous time series of livestock weight gain that is available is mainly only through the Central Plains Experimental Range, and shorter datasets starting in the 1980s are available from Cheyenne. Justin, would you like to elaborate on other stations?

>>Yes, EJ. For -- Tip, for -- in terms of some of the livestock production data, there are some long-term history data up at Mandan, North Dakota. That study has been completed, though. There is long-term forage production data from sites such as Santa Rita and Arizona, and the Jornada down in New Mexico, but again, very few sites. And having sites with both livestock production and forage production are quite rare across the North American plains.

>>Yeah, that's what I thought. I think I saw some years ago some long-term data on species composition from the research station in Utah, that they were doing something similar. It was a retrospective look at how different climate variables affected species expression in particular. And I think this was one where, you know, back to back years of above average, spring precipitation precipitated a significant change in species composition because you had one year where there was greater viable seed production. And then in year two, you had a climate that allowed the germination and the establishment of that seed. And so you had this really punctuated change in vegetation expression. Some of that kind of stuff, you can't tease out without these long-term sites being maintained. Then, you know, when you have grant cycles that operate on two, three, you know, on the outside, five years, it seems like, it's hard to maintain funding to keep those kinds of thingup. But that long-term data has tremendous value, I think.Well, I want to go back to a question about how to articulate grazing pressure. I've been studying rangeland ecology since about 1995 when I went to college at the University of Idaho, and I still find it difficult to, I guess, articulate a metric that communicates the variables of time, and vegetation removal, and animal density. And maybe there's not a good way to do that, maybe the thing that we have to do is to just describe all of those variables. In the extension publication on this project, we used AUM's per acre to distinguish among light, and moderate, and heavy. And we talked earlier about that -- those numbers really corresponding to approximately 20%, and 40%, and 60% utilization of annual net primary production. I know if we articulate grazing pressure in terms of pounds per acre, that's only valid with a specific amount of forage per acre that you're working with. And so -- and those might be different plant committees. For example, in the shrub bunchgrass, plant communities have much of the intermountain west in the Great Basin. You know, a 40% harvest coefficient or annual utilization level might be sustainable, but maybe not if it happens during late spring every year. And it happens in such a way that, you know, total herbaceous removal is approximately 40%, but that happens to prevent seed production every single year. So to those -- do you have any thoughts on a metric that combines animal demand, forage supply, time, and I guess by time, I mean, duration of use which is even something different than the season of use and area into some kind of a grazing metric? And does it need to look different for different places?

>> Yeah. So Tip, that is a really challenging question you just put together there. And I agree that it's one that we think a lot about in range -- in the rangeland world. And I think most people do approach thinking about stocking rates from a utilization standpoint, and that is valid and important to do. And, you know, we have our traditional take half, leave half rule. That's our rule of thumb for how we want to maintain sustainability of grazing lands. But I think it's also -- for me, I think it's really important to think about the evolutionary history of a given type of rangeland that you're managing. And, of course, there's a big difference between the history of the Great Plains grasslands versus the shrublands and grasslands of the Great Basin and the Southwestern United States. They just have -- the plants have different traits, and therefore, have different levels of grazing tolerance. And so here in the western Great Plains, I think our rangelands, you know, because they've been subjected to intense grazing by native herbivores for thousands of years, they do have -- they can sustain a higher level of offtake, perhaps, than what might be considered sustainable in a different ecoregion. And so I would just point out that EJ, and Justin, and I also recently published some work analyzing sustainable stocking rates, where we did it from the perspective of the animal weight gain, and what is a sustainable stocking rate as dictated to us by the animal performance? And what we actually find is, is pretty -- oursustainable stocking rate is slightly above what we historically consider moderate, and probably somewhere in between what we call moderate and heavy is a sustainable stocking rate for this region. But, yeah, it is very difficult to put an AUM per hectare into context. I understand that. And that's why we do have to have careful thought about this at many locations throughout the western US.

>>Yeah, I was interested in looking at some of that livestock production data in there. I would have said if somebody had asked me cold what livestock production would look like under those different stocking rates, I would have said that under lighter stocking rates, and we could -- in this case, we can communicate that as animal density or percent utilization under --you know, let me go back. Under light stocking rates or livestock density, individual animal performance would be high. But herd performance might be lower just by virtue of having fewer animals. And that sort of like, you know, your economics profitability curve where you're trying to aim for where marginal cost equals marginal revenue, there's something similar going on. And maybe that's the tipping point that you just described, that somewhere between moderate and heavy, or what has been called somewhere between 40% and 60% utilization, at least on the Great Plains, seems to be that sweet spot where you're not sacrificing per animal performance, but there's also enough animals that you're capturing and economically relevant harvest, I guess, without compromising the integrity of the plant community. Am I getting anywhere close on that?

>>Yeah, that's exactly right. And the question is, does that inflection point that you just described, does it correspond to sustainability in the plant community? And there might be rangelands where it does not. And -- but what we find in ours, it does appear to -- in other words, finding -- managing around that inflection point probably will not cause long-term, irreversible degradation of the rangeland. And fortunately, we have long-term datasets to show that.

>> Right, because those species tolerate a higher percent plant removal. They tolerate more severe defoliation than some of the other plants like a bunch of grasses that are totally dependent on seed production for reproduction.

>> Exactly.

>>I guess my last question is, there's -- there are an awful lot of what I believe will be pretty useful technological tools coming online, pardon the pun, that I think are almost, you know, sort of back to the future kind of technology in the same way that we've begin -- began getting back to integrating livestock and crops because there's the potential to improve soil organic matter, then reduce the amount of synthetic fertilizer applied. There's some natural synergy there. I think there are also some ways in which these newer technologies and things like virtual fence may permit, you know, almost a return to more old-fashioned herding, where, you know, you've got animal sensors that may record other things besides just a geographical location that can be used to make decisions on the fly in a way that we haven't been able to before. Do you see some of those things like virtual fence being able to allow hitting this sweet spot in terms of stalking and also doing it in a way that gives us maybe better early warning signals of, you know, leading indicators of a decline in rangeland health plan community health so that we can make quicker decisions?

>> Yeah, I guess I would -- I think I would point out -- I think there's two technological developments that are really important. One is the virtual fence that is just starting to emerge. The other one, as I think we're finally starting to see the development of truly useful remote sensing tools that can help us provide -- or can help provide us with more real time monitoring of available forage on the landscape and how that varies both spatially and temporally. So within our research unit, we have another scientist,Sean Kearney, who's been leading that effort, and we're starting to develop dashboards that take real-time data from freely available satellites and turn that into predictions of available forage biomass. We're also trying to make real-time maps of forage quality so we can then take that information. So now, we can see the variability in both forage quantity and quality on the landscape through the remote sensing and then apply or use our virtual fencing in combination with that to really think about how we want to move the animals on the landscape in response to what's available. So I think using those two technologies in combination are going to be really valuable as we move forward. And we'll be piloting a couple of studies at our experimental range. And I know several other experimental ranges around the US that are moving in that direction as well.

>>Yeah, I think that is pretty exciting. I just -- one quick thought that comes to mind is that in most places, fences were placed based on legal boundaries and not ecological boundaries. And oftentimes, those fence lines don't make much sense in terms of how animals would use the landscape or -- and how they ought to be managed in order to protect the landscape in terms of having grazing use that is appropriate for a given plant community. And I feel like that's one of the biggest potential benefits of virtual fence is being able to make grazing boundaries that makes sense ecologically and aren't stuck with barbed wire that's 100 years old that follow the section line because that's where the ownership was. Is there any other research that you're aware of on these big picture connections between climate and livestock production that's in the works right now?

>>I think the whole arena of precision livestock management is really developing right now. A lot of different methods for communicating between a rancher and his animals using on animal sensors. So that's virtual fence. There are other developments out there looking at tracking foraging behavior that can tell us how well the animal is performing within its current environment. And like I said, the remote sensing, putting that all together into a complete management system is, I think, just really exciting and has so much potential. And I also certainly agree that not having square grids of 100-year-old barbed wire fence on the landscape opens up a lot of new possibilities for management.

>>Justin, you want to add to that?

>>Yeah, I think David's spot on with some of the technological advances. I just wanted to reiterate that the big data aspect of pulling together multiple datasets is really emerging, Tip. And so I think you'll see some available datasets and retrospective looks from remote sensing that could be combined to look at historical data that hadn't been collected yet on the field, but could provide some loose avenues for decision-making trees and decision-making approaches that would help across larger regions than just a site specific ones we have here, Tip.

>>Yeah, that sounds encouraging, this idea of having more high-quality data. And I guess by quality, I mean, accurate data at large scales, you know, at the landscape scale on forage production, but also greater control of livestock at smaller scales, I think, has great potential to be good for rangeland health and animal health. And I like this idea of using animal health as a gauge for whether or not we're stocking appropriately. I mentioned earlier that we'll put the Colorado State University Extension publication that describes this research and shows the decision tree that describes potential stocking decisions based on these combinations of PDO and ENSO. But is there some place where people can find, I guess, the native data on what those ocean oscillations are doing presently?

>> To find the information that would be able to inform you whether you were within a La Nina, or a neutral, or El Nino phase of that ENSO, you could go to the National Weather Service's Climate Prediction Center. And they have a repository for monthly changes in the -- both of those large scale climate modes. And you can email various scientists if you need more in-depth information.

>>Yeah, that's great to know. I've got a follow-up question on that. On the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration website, they have these seasonal predictions that, you know, for example -- and I think a lot of ranchers are familiar with those, where you can -- you could pull up what the prediction is for, say, November, December, January weather temperature and precipitation are likely to be higher or lower than average. Dothose averages -- and maybe you can speak to this, but do those seasonal forecasts come from largely these ocean oscillation predictions?

>> Yes, Tip.Those are often influenced by the trans in terms of the PDO and the ENSO signals, as well as any other larger scale climate aspects. However, the reliability of those, Tip, in the Great Plains is still to be vetted and has some issues in terms of its reliability, especially in the spring.

>> Sure. And I understand that you're saying it's more useful for producers to have access to the raw data, I guess, on PDO and ENSO so that you can identify whether or not they're in phase, out of phase, and combine that with, you know, with these more near term forecasts to make a good decision about it. Yeah, we'll provide a link to that website that offers the ocean data as well.

>> Right. Well, I would say that we're indicating that data analysis needs to be conducted. But, for example, you Google National Weather Service Climate Prediction Center right now for the nets grazing season, there's a 54% chance for the El Nino Southern Oscillation to be neutral. And that, therefore, leads to evaluating local precipitation forecasts when setting your stocking rates. That's the type of information that we're referring to in these nice texts written by NOAA about an El Nino -- the El Nino alert system.

>> Great. Thank you. Well, I -- it's exciting to see research that has already application, you know, for the people whose livelihoods depend on making good decisions about these things. And I appreciate the work you guys have done and appreciate the folks that have kept up these experimentations for the long haul. And I want to thank each of you for your time today. My guest has been Justin Derner, David Augustine, and EJ Raynor. Thanks, guys.

>> Thank you.

>> Thanks a lot, Tip.

>> Thanks a lot for having us, Tip. It's been great, and I appreciate you highlighting this work.

>> Thank you for listening to the Art of Range podcast. You can subscribe to and review the show through iTunes or your favorite podcasting app so you never miss an episode. Just search for Art of Range. If you have questions or comments for us to address in a future episode, send an email to show at artofrange.com. For articles and links to resources mentioned in the podcast, please see the show notes at artofrange.com. Listener feedback is important to the success of our mission, empowering rangeland managers. Please take a moment to fill out a brief survey at artofrange.com. This podcast is produced by Connors Communications in the College of Agricultural, Human, and Natural Resource Sciences at Washington State University. The project is supported by the University of Arizona and funded by the Western Center for Risk Management Education through the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

>> The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed by guests of this podcast are their own and does not imply Washington State University's endorsement.

Best website for PDO and ENSO info.

NOAA website on Pacific Decadal Oscillation.

El Nino/Southern Oscillation information from NOAA

Colorado State University Extension publication "Early Warning for Stocking Decisions in Eastern Colorado".

Journal article in PDF, "Large-scale and local climatic controls on large herbivore productivity: implications for adaptive rangeland management", in Ecological Applications (2020).

And "Forum: Critical Decision Dates for Drought Management in Central and Northern Great Plains Rangelands", in Rangeland Ecology & Management.

Other publications by Justin Derner and David Augustine.