AoR 103: Pasture, Range, & Forage (PRF) Insurance with Matt Griffith

The PRF program insures against unusually low precipitation during 60-day periods critical to your forage growth, unlike drought insurance, which typically is based on annual precipitation over a water year or calendar year. Matt Griffith of WSR Insurance in California explains how PRF works in this episode in our ranch financial resiliency series.

Transcript

[ Music ]

>> Welcome to the Art of Range, a podcast focused on rangelands and the people who manage them. I'm your host, Tip Hudson, range and livestock specialist with Washington State University Extension. The goal of this podcast is education and conservation through conversation. Find us online at artofrange.com.

[ Music ]

Welcome back to the Art of Range. My guest today is Matt Griffith with WSR Insurance, out of California. Matt, welcome.

>> Thank you, Tip. Nice to be here.

>> Well, I appreciate you jumping on. We've, we've interacted just a, a few times, and, but Matt is a partner on this current grant on ranch financial resiliency, and specifically the grant that we're working off of is trying to put people together with insurance providers. We've, We've done a fair bit of discussion about livestock risk protection, and have talked less about pasture, range, and forage insurance. And most of these insurance companies that serve livestock producers handle all of those. But WSR Insurance has been around for a long time, and Matt has been doing this long enough that he, he knows his stuff. Matt, how did you get into, how did you get into doing livestock insurance?

>> Well, Tip, that, that's kind of a funny story. I'm a fifth generation rancher from northern California, and the product, pasture, rangeland, and forage, was presented to me in 2011. I became a customer of the product, and I worked with it on that side to see kind of the backside of the policy that the customer sees for three years before I became an agent and was licensed to sell the pasture, rangeland, and forage product.

>> Yeah, and were you, were you part of an insurance company before that, or just raising cattle?

>> No, I, I didn't have any type of insurance background before that. My, my only occupation had been on the ranching side, and I was a partner with my father in, in the Griffith Livestock, and unfortunately he was in an accident, and Jim Van was working here at WSR, and he offered me a position to come in with the PRF product, and because I had experience with it, I felt comfortable with showing it to, to others in the ranching industry.

>> Yeah. I want to come back to the, to the, some of the ranch history, but what else does WSR Insurance do?

>> Well, Tip, WSR was established in 1917, and we're a full-brokerage agency. So no matter what you're looking for, if you're looking for your commercial and liability, or your worker's comp, health and benefits, there's somebody within the office that can service all of your insurance needs. We have a large crop insurance book that is my focus, but within the agency there's an agent that can handle any of, anybody's insurance questions or their needs.

>> Got it. Well, going back to the ranch, you know, California's notorious for being especially volatile in terms of rainfall and forage production, and maybe that's, that's somewhat the case all over the west, but it seems to be more that way in California, partly by virtue of having mostly annual grasslands that tend to be flashier than perennial grasslands in general. But what was your, what was your experience raising livestock in California, in terms of, you know, forage availability?

>> Well, where we're based, Tip, we're an hour north of Sacramento in a town called Williams. It's on the west side of I-5, and really it's kind of a feast or famine type scenario. Historically our rainfall is right around 16 inches annually, so on a normal type year, we have a real heavy clay soil, and the feed production is outstanding. We, we run yearlings in, in our spring months. They'll do two to even two and a half pounds per day when there's adequate rain. The trouble with that is it's hard to know when that rain's going to happen. A lot of years we are on definitely the drier side of the state. So that's why PRF was so appealing, as a customer, just due to the fact that we're bringing in yearlings, expecting them to gain 250, 300 pounds for the spring season, and if it doesn't rain, they kind of go out the same weight they came in at.

>> Uh huh. Yeah, and at 16 inches, if you get 50% more than that, that makes for a lot of grass. If you get 50% less than that, that's a pretty extreme forage-short condition.

>> Absolutely. Without, if, if we're going to be 50% less than our historical average, things get pretty bleak pretty fast, and it's not, it's not a scenario anybody wants to be in, because then you're kind of scrambling to find other inputs, and nobody wants to be in that situation, and it can escalate quickly over here in, in the northern part of California.

>> Yeah. Yeah, we definitely feel it in the central part of Washington State. I live in Ellensburg, which receives an average of, like, eight and a half to nine inches of precipitation annually. But because the wintertime precipitation pattern, that is relatively reliable, and we don't usually get, you know, large swings away from that. And, and because you get some winter precipitation, you know, something happens every year. But if you're relying on more growing season precipitation or, you know, you run out of moisture by the first of May, that, that really puts a clamp on things.

>> Yeah.

>> What, what does the volatility look like in, in your part of the world?

>> Well, most years, I mean, the volatility factor is fairly extreme. Looking at, like, last year in 2022, it, recent history, January and February, we came in at pretty much zero, and those are our two wettest months. So it's really devastating whenever you see any decline from your normal precipitation, but to have it be absolute nil, I mean, it was devastating as far as, not only your, your, your grasslands, but your drinking water, kind of everything, it kind of all hit at once. And, now that was an outlier. That hasn't happened before. Last year was the driest for, for that, that 60-day period in recorded history, but even the year before that, when we were in a La Nina pattern, La Nina typically means drier than normal for most of California, and to have it be, it was just compounding year after year, because we received 40% of normal the year before for our, our wettest two months, and then to go with a zero on top of it the following year. As these drought conditions, as these drought conditions just stack up on each other, then the result becomes even more extreme.

>> Well, we're talking today on the, in late March 2023, and I don't even watch the news, but I'm aware that California's been getting hammered with a lot of rain, and it's causing some problems. Is that, is that occurring everywhere, and is that going to be useful in July, or, or is all that water going to run off and not do you a whole lot of good.

>> That's a, that's an interesting question that has lots of different levels that we would have to unravel, but yes, for the state has a whole, from the top to the bottom, 2023 has been, for the most part, well above average for most everybody. And without jumping into too much of the politics of California, a lot of our issues come from water storage, but it looks like this year, if you're going to be in an irrigation district, say you have permanent pasture, you're going to be in good shape. Now, the trouble that we have is with the outflow and what we have to release on an annual basis. We kind of have to have normal to above average precipitation annually for that, that year's summer to have water availability. It's a, it's a complicated question where you have lots of different agencies fighting for the same water, and we're not great on storing any extra in the state.

>> Uh huh. I realize that WSR covers an area larger than California. I'm asking questions about California just because I, I know less about it, but in California, it looks like most of the beef cattle are down the central valley and in the, the foothills on either side towards the coastal range, and then toward the Sierra Nevada's. How much of, how much of beef cattle production in California is reliant on irrigated pasture, and how much on, you know, rangeland or dry forest types?

>> Yeah. I don't have the exact answer, Tip, but the permanent pasture situation in California, people have been removing pastures just because of the lack of continuous water, and they've put in some other type of crops. If I was going to estimate it, I'm going to say, you know, it's going to be somewhere along the lines of 90% are on non-irrigated pastures, where you're dependent on precipitation for your grass growth.

>> Yep.

>> There's just too many other commodities that have came in, that have kind of taken the, the pasture ground away.

>> Yeah, that have higher per acre revenues.

>> Exactly.

>> Profit margins on irrigated ground, yeah.

>> Exactly. What we're seeing is a lot of trees have gone up in the state, just because when, when the water source is lower, and you're having to pay an additional cost for that water, the trees were the better option. Now, that dynamic has kind of changed this last two year with, with the price of almonds, walnuts, pistachios, but for the previous decade before that, a lot of, a lot of ground went that way.

>> Okay. Do you happen to know off-hand how many beef cows there are in the most recent ag census for California? What's the beef cattle inventory?

>> Well, I'd have to look that up. I apologize. I [inaudible] per head.

>> Oh no. Yeah. It's quite a few. It's a lot more than, Washington State actually has roughly equal amounts of beef cattle and dairy cattle, and that's part of where my question was going to go. Is it roughly an equal split in California as well?

>> No, I think the beef cattle now would be well ahead of the dairies. We've seen a lot of dairies leave the state, and it's a, it's, it's a sad dynamic, and a lot of that is, you know, state regulations and what not, so the dairy industry has been, has, has suffered.

>> Yeah. I actually don't know that much about pasture, range, and forage insurance, other than what I've read, you know, briefly in preparation for this interview, but the idea of insuring, insuring against rainfall seems like it would be a, a difficult proposition. So this is one of the federally subsidized risk management products available or provided sort of through USDA Risk Management Agency. Can you describe a little bit of, of what the program is and, and how it works?

>> Absolutely. So, Tip, with the pasture, rangeland, and forage program, commonly referred to as PRF, what you're doing is you're insuring two-month, what we call intervals, up to their historical average rainfall amounts. And that rainfall data is collected by the NOAA Weather Service. So it isn't the rain that you get on your location, it's an area-based policy. And that area is typically a 12 by 17-mile grid, and within that grid, hopefully there's a NOAA weather station or at least one. Most grids in California have more than one that is collecting the daily precipitation data, and that number is recorded on a daily basis to use as your 60-day average. So each two months is its own mini insurance window. It doesn't, a lot of times people have the misconception that PRF is drought insurance. That is absolutely not accurate, because each interval has its own average and its own, it's its own insurance policy. So, like in California in 2023, as we speak, January and February is, is not going to pay any claims. But that doesn't mean that April-May is affected, because there's no, there's no carryover for the extra rainfall. You just start again at zero. So what we try to do is much coverage in the intervals that have, there's a couple of moving parts, but in theory, you want to coverage in the intervals that are most important for your grass growth, and within the state of California, depending on where you're at, those interval options that are available change at the bottom of the state. If we're in, say, Brawley, you're going to have January, February, February-March, and then November-December that you can have protection in, that you can pick from. If I'm up in, say, Alturas, in Modoc County, I have the whole year available. So we have such a, the state is so diverse in our weather patterns, the intervals that are available change county by county, but it's still the same principle. You would like to insure your intervals that are most important to your grass growth, and then what we also do is we look at the frequency of a claim to know which intervals have the highest opportunity of, of actually capturing a loss. But, with that being said, pasture, rangeland, and forage is a program that is available to every rancher. You don't have to do all of your acres, and there's different coverage levels that have different subsidy amounts available as well. So if I choose to insure 70% of my average rainfall in that two-month interval, then the USDA has a subsidy of 59%, meaning the rancher can receive 100% of the claim activity, or the benefit of PRF, and only be paying 41% of the total premium. If I go, and that's the lowest amount, the 70. Now if I go clear up to the highest, at 90, which we don't write a lot of 90, usually there's a better option, but if you wrote it at the 90%, covering 90% of your historical precipitation, then the subsidy decreases to 51%, meaning that the rancher is now responsible for the 49% of the total premium.

>> Huh. Yeah, that's interesting.

>> And it's all based off of these NOAA weather stations, so when I sit down with a potential customer, the first thing we do is we map out your ground. I need to see what grids the ground lies in, because each grid has its own history of how PRF would have performed. And so typically when I'm sitting across from a, a potential customer, we pull up 20 years' worth of data, we show the, the frequency of claims, what general has generated the highest claims, and then we kind of work our way backwards to come up with a budget that fits the, the, the rancher, that operation, just because of the fact that it's a per-acre basis. You don't have to do all of your acres. We actually, at WSR, encourage customers to, to take us, take us for a spin first, and then we can always add to the policy if it's beneficial to the rancher. Our agents come from livestock backgrounds, every one of them that works with this product, so we kind of understand how, you know, the ranching industry as a whole, a lot of years there's not a lot of profit margin there, and our goal is to always do what's best for the customer. I, I, I kind of feel like, by starting with a budget, we're safe that way, knowing that, hey, if it's a wet year, that you're going to be able to pay the premium, either based off of your, your highest stocking capacity or your, your, your weaning weights, or your yearling gains being [inaudible].

>> Uh huh.

>> That's how we, that's how we can offset the cost.

>> Uh huh. How does it work on, on leased ground? Yeah, most, at least around here, most ranchers are running on a variety of properties that, that aren't necessarily deeded property to them. You know, lease to another private owner, or state ground, or federal ground. How does it work on, on land that you've got a permit or a lease on?

>> That's a good question, Tip. With PRF, there is no difference between your owned, your deeded ground, and your leased ground, whether that's a lease that you have with your neighbor or BLM, Forest Service, state lands. The rates are all the same. And it.

>> You just have to verify that you've got the lease.

>> Correct. If we, once we get in an audit situation, I'll need documentation showing that you have the lease for the acres that we have insured, and that's kind of the only requirement for the actual ground itself. The other thing you have to do is you have to be the person owning the livestock or having an insurable interest in the livestock to participate. So if I'm an absentee landowner and I lease out the whole ranch, I can't do PRF. I don't have any interest in it, unless there's a few, few minor instances where you could be taking cattle in on the gain, and there's some opportunity there, but for the most part, if you just lease out the ground as a cash rent by the acre, you're not eligible for the product. That goes to your tenant, who now how the insurable risk, because he's paying you. So if it doesn't rain, he's the one that suffers the loss.

>> Yeah. Do you find that people sign up for the program depending on what the various weather viewers are saying about what the year's going to look like? Like, right now they're saying that we're, we've got a strengthening El Nino that's going to potentially take over, or do most people just sign up every year, knowing that no matter what the weatherman says, there's a fair bit of volatility, and you can't trust anything?

>> Well, every scenario's a little different, and every customer has a different outlook on that, but as a whole, I will say, the El Nino means, for a lot of the state of California, we're going to be wet. A lot of our customers, we'll advise them, hey, let's short, let's shrink your coverage, and maybe we focus on the back end of the year, if the projections are that we're going to have a really wet winter, because the El Nino, that, when we have that forecast, we, that's fairly accurate, where we know, especially for the southern half of the state, that they're going to receive rainfall, at least typically in the winter months. Now, the funny thing about that, and looking at the 20 years on a software program that we have, we'll just pull up El Nino years. And so we can show you over, actually it goes back 70 years, where we can pull the El Nino data to show which intervals still are drier than normal, and then we just, we just relay that information to the customer, and they kind of make a decision. But typically El Nino years mean people have a little less coverage overall, up and down the state.

>> Uh huh.

>> When I get to the, when I get to the, the top of the state, El Nino typically isn't a good thing. So as I'm approaching the Oregon border, they're, they're less likely to receive the rainfall that, say, the San Francisco bay area will on an El Nino year.

>> Uh huh. Yet in terms of the signup period, you said you want to insure intervals that are most important for grass growth. Like in the Pacific Northwest and probably some of the areas on the other side of the Coastal Range in California, you know, we, for cool season grasses, we're dependent on April and May precipitation, which usually isn't much. If, if I wanted to insure, you know, April 1 to May 31st, is it too late to sign up for that?

>> Oh, yeah, no, Tip, and, because it's an annual-based policy, that's a very good question, and that does pop up a lot. We have, our, our sales season typically begins with the next year's rates on September 1st. So if I'm looking at a 2024 policy, because it's an annual policy, and we're too late for this year, rates come out the first part of September for the following year. We have to have applications signed by December 1st. So that's our sale season. It's pretty short. It's 90 days.

>> Got it.

>> And, and that covers the entire 12 months of the following year.

>> Okay. No, that makes sense. So now's a good time for people to be considering signing up for 2024, because they've got a few months to think about it and they can start signing up in September?

>> Absolutely. Yeah, we're doing meetings right now with customers that are interested, just to show what the product looks like. The first part of September, when we have rates, then we circle back and we can talk about what the premium could look like in coming up with a, with a plan for the policy before that December 1st deadline.

>> Right. A couple more questions, can you describe a scenario in which PRF would not pay anything out? Say I'm a, a rancher in, you know, central valley California, and I'm interested in, you know, whatever would be the, the most important window for growth in that part of the world. What, what kind of circumstances would result in me paying a premium but, but not receiving any payment back, and then vice versa, you know, what does the scenario look like in which PRF does pay?

>> Well, for WSR and our customers, 95% of our policies are wrote at that 85% coverage level. So that's insuring 85% of your historical rainfall, and that rainfall began, NOAA started collecting that data over 70 years ago. So one or two really dry years or really wet years doesn't change your historical amount much at all, just because you're just adding another year onto that, but in, in this type of setting, where the PRF wouldn't pay, it would be us selecting an interval like January and February and receiving 85% or more of your average precipitation. This year, for most of California, this January and February interval that we just finished, it looks like the estimated rainfall for the, for the state will be somewhere along the lines of 130%, so we're not going to pay any indemnities. The full premium is owed for that interval. Now, if I have January and February, and let's say I'm only in one grid, my next option to select insurance would be March and April. Now, March looks like it's well above normal for the most of the state as far as precipitation, but we haven't started April yet. If April comes in, and let's say it's average, then that, we're not going to pay a claim for most of the state in that interval either. And after that, if I'm in the central part, that might be my last interval to, until the Fall. So coverage could start back for a lot of the state and the central part, in September-October. So if September and October are 85% or higher, you're going to have a full bill. So what we're looking at is each interval as its standalone insurance policy, and if every interval that we select to place coverage in comes in above 85% or at 85% or higher, then there's no, no credit to your policy. You would be looking at the full premium amount, which, you know, we, we look at 70 years' worth of history from NOAA. We try to come up with a plan, but you know, the weather's an independent variable. So as an agency, when we go see a customer or potential customer, we talk about, hey, this, this is a real-life scenario where you could have the full premium amount based off of the intervals that you select coming in at 85% of your historical average or above. This is the maximum premium that could be owed. Because there is no penalty for going above the average, so when, when we're, when we're in discussions on if a person wants to participate in PRF, we know the worst-case scenario, what the bill would look like, the, the total amount.

>> Uh huh.

>> Our, our thought process is, we want to come up with something, if that's the scenario where you're looking at the full premium, I can sit across from you and feel very comfortable knowing that we have multiple intervals selected. We have our coverage in place to benefit the rancher, whichever they choose, and if you have to pay a premium, you, in theory you'd better have a really good grass year. And, you know, the, the extra grass that you have to either, either increase your stocking capacity or increase your rate of gains offsets the bill.

>> Right. Right. No, that's helpful. If you were trying to, as you likely know, a lot of times livestock producers are not real excited about participating in federally subsidized programs, and this is an interesting hybrid, where it looks a bit like an insurance product, but, but the cost of the insurance is subsidized through the federal government, because, I presume because there's, federal government has an interest in, in protecting food producers. How, how would you say you have seen both PRF and LRP received? It appears to me, you know, through the, through the RMA website, you can see some of the historical data in terms of enrollment numbers, both the individual producers that have been enrolled, you know, by state, as well as the number of head enrolled, and you can kind of, I've compared some of that in terms of head enrolled versus, you know, the state's beef cut inventory, and it's still relatively low in a lot of places. How would you say the reception has been to some of these products? You know, with a clientele that I would say has been more skeptical of things like subsidized insurance?

>> Yeah, and, and it is a different, it is a different industry, so with my background, my family, we've farmed and ranched. You know, farmers have bene participating in crop insurance since the 80s, and most farmers don't operate without it. Now, the ranching industry, up until PRF, there really wasn't a product. I mean, you could go to FSA and sign up for NAP, and depending on where you're at and your county board, you know, NAP usually didn't trigger, so a lot of, a lot of rancher were turned of by it. So it has been a slow and steady, gradual climb, I would say. I begin selling, selling PRF in 2013. My first policy years that went into effect were that 2014 year, and at that time, it did take a lot of persuasion. I will say, within the last 10 years, that the environment's changed, and more people now know about the product and how it works. If you do not want to participate in anything that's subsidized, that is totally understandable, and I get that quite a bit still. Like hey, we're, we stay out of anything that's USDA-involved, and that's, that's the rancher's own prerogative. I will say that, you know, with any crop insurance that's available, you're partnering that with, with your, with your food bill, so it goes with the nutrition program, so they, they go hand in hand. The USDA is concerned about food scarcity, and this is just a way to ensure that, you know, the ranching industry stays viable for future generations, is kind of how I look at it. You know, ranchers pay their taxes just like anybody else, and, and this is just a, another offshoot of what's available with that tax, with that, with that tax, with those tax dollars.

>> Yeah. A couple more questions. You, you said that PRF is not drought insurance. What, what does drought insurance look like, just to kind of draw the contrast and see how they function differently?

>> Well typically, Tip, when we're speaking on drought insurance, that would be on an annual basis for the whole year. So when we speak about drought, that's usually based off of your typical, your water year, whatever.

>> Yep.

>> When it starts in California, you know, we're going to, where I'm at, we're going to run, kind of October through May, and then we don't expect much. But with PRF, and these two-month intervals, it doesn't have to be a drought to trigger a loss. And that's a real.

>> Right.

>> That's a real-life scenario for a rancher. Because I can have all the rain I want in January and February. I might get, like this year, you know, we got 20 inches, but if it doesn't rain in April-May, and I don't have that forage available, I'm still suffering.

>> Uh huh.

>> So PRF is, is an avenue where, that you can have coverage in that timeframe to make up for any losses you incur. So that, that's kind of the difference. Drought is typically your, your annual rainfall amount. The drought programs, like if I'm talking about NAP at FSA, or LFP, you know, they're looking at just the drought monitor, things of the sort, where PRF, you just have these 60-day windows, and whatever rainfall amounts or snowfall that NOAA captures in their approved weather stations, that's what they're basing it on.

>> No, that makes sense. It's quite a bit more relevant to forage production. And, and yeah, in, in much of the west, especially the northwest, we get most of our precipitation as snow, and if you've got 3 feet of snow on January 1 but no rain after March 15th, by the time you get to the middle of May, that 3 feet of snow isn't making much difference.

>> Exactly. And, and for this program, they measure everything as, with the PRF, they measure everything in the amount of rainfall precipitation. So the equivalent would be 8 inches of snow equates to 1 inch of rain.

>> Uh huh. Well, if, last question here. If, if, if somebody is interested in working with a, a rep to look at what PRF would look like for their specific grazing areas, what's the best way to get a hold of somebody?

>> Well, Tip, I appreciate that. WSR has a team of PRF agents now. We're up to 21 of us, and we are spread out throughout the United States. The easiest way would be going to wsrins.com, and that's our homepage for the, for the agency, and then there's a farm and ranch tab. If you click on that, you have the option to go to the inquiry page and shoot over an inquiry, and the agent that's in your regional area will be reaching out to you, and we're doing that as we speak. I am also available at Matt G at wsrins.com, if somebody wants to email me, and I can get them lined up with their, with their regional agent. Those are the, those are the two best ways to reach out.

>> Yeah, that sounds good. We will, I will put those links in the show notes. And maybe just a teaser here for a future episode, one of the discussions that you and I had a while back was talking about the possibility of trying to let people know that there are careers related to agriculture that aren't necessarily working for a pharmaceutical rep, and I think we should talk about that sometime soon. But do you guys have, do you have any thoughts on that right now in terms of young people that are looking for a career in agriculture?

>> Yeah, Tip, absolutely.

>> Probably insurance wouldn't be the first place they would think of.

>> They might not think of crop insurance, but as a career, I've found it very rewarding, and the USDA is always coming up with these, what they call pilot programs, so the crop insurance that my father used and my grandfather used, that world is changing dramatically. I'm going to use a product that's been around for three or four years as an example. Besides PRF, it's whole farm revenue, where you can actually insure the revenue of an operation, and it's also subsidized based on the amount of commodities, but there's things like that instead of doing a single peril, that you can have an umbrella type policy for the operation, and there's these, and younger agents that are coming in, we're, at WSR, we're always trying to find somebody coming out of school that is interested in risk management, just because they're up to date with technology, usually, you know, they're versed in the newer products. It's not like having to reinvent the wheel, so I would say, for a college-age person looking for a career, that crop insurance is a great avenue. I don't think it's going anywhere. Most of the nation is now participating in some sort, and their regional products available, and there's always going to be a need for somebody to go service those, those, those farmers and ranchers.

>> Excellent. Yeah, it, you know, there are, most of the time when a ranch goes under, it's because of financial problems, and, and so young people are, are typically looking for something, looking for a career where they feel like they can be useful and enjoy the work, and I have thoroughly enjoyed, you know, working directly with, with ranchers all over the west, but especially in Washington State, and helping people, you know, be able to weather both the financial and, and meteorological storm, so to speak, is, is pretty important work, and it can be the thing that makes or breaks a ranch, and we definitely need to hang on to the ones we've got.

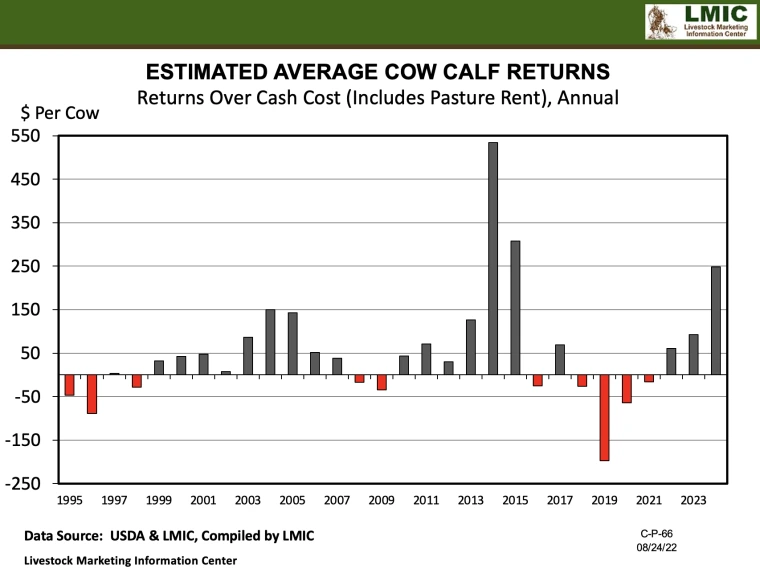

>> Absolutely. You know, and, and industry as a whole, you can see the amount of just exposure to risk increasing year after year. It costs so much to be in the ranching industry, but there are these products that are available now to help protect you. You know, in my mind, your two biggest, your two biggest risks are going to be the weather, and it's going to be, you know, guaranteeing your price. So between the, the pasture, rangeland, and forage, which helps offset the weather losses, and the LRPs, where you can insure against the CME Final Index, there are options where a rancher just doesn't have to be out there, kind of out in the wind, not having any type of a safety net. And there's other products that are, that are coming up, that we're excited about, that I think will also be beneficial to the ranching industry as a whole.

>> Great. Well, I look forward to visiting about that. Matt, thank you for what you do, and thank you for your time, and we'll be, we'll be putting some information on how folks can get a hold of somebody who can help them think through how this might work for them. Thanks again.

>> Tip, I appreciate the opportunity, and it was good to visit with you today.

>> Thank you for listening to the Art of Range podcast. You can subscribe to and review the show through iTunes or your favorite podcasting app, so you never miss an episode. Just search for Art of Range. If you have questions or comments for us to address in a future episode, send an email to show@artofrange.com. For articles and links to resources mentioned in the podcast, please see the show notes at artofrange.com. Listener feedback is important to the success of our mission, empowering rangeland managers. Please take a moment to fill out a brief survey at artofrange.com. This podcast is produced by Connor's Communications in the College of Agriculture, Human, and Natural Resource Sciences at Washington State University. The project is supported by the University of Arizona and funded by the Western Center for Risk Management Education through the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

>> The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed by guests of this podcast are their own and does not imply Washington State University's endorsement.

[ Music ]

USDA Risk Management Agency main PRF page

WSR Insurance page on PRF

USDA Risk Management Agency FAQs on PRF